Prior to Russia’s full-scale invasion, Ukraine was experiencing a problem only too familiar in developed countries: an ageing population. Using UN-sourced data, Eban Raymond explains how, amid the ravages of war, Ukraine now faces a demographic crisis, with severe implications for its economic recovery

The European Union estimates a decline of 6% in Europe’s population by 2100. Ukraine is on course to make up a significant part of this decline. The country’s priority will be its immediate post-war economic recovery, then tackling the war's long-term economic and social effects. A declining, ageing population will put a strain on public services and shrink Ukraine's labour force. Meanwhile, the country must painstakingly de-mine huge swathes of land – a process which may take up to thirty years.

Yet, Ukraine’s economic problems were in the making long before Russia’s invasion in 2022, and even before its proxy conflicts in the Donbas. After gaining independence in 1991, the young country was swept by hyperinflation. This culminated in severe economic decline relative to the Soviet era. More than 2.5 million people left the country between 1991 and 2004. Many of these emigrants were young, which reduced yet further Ukraine's ability to sustain its population in the long term.

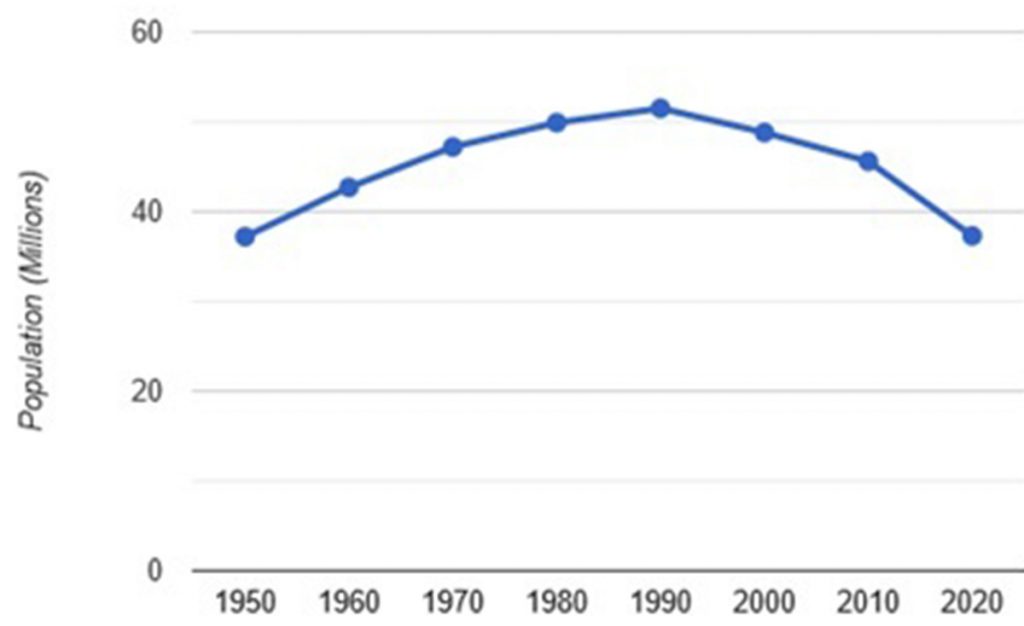

Following a peak at the point of independence in 1991, Ukraine's population has since shrunk back to its 1950 level

Ukraine has faced similar demographic challenges in the past. After the Ukrainian Soviet Republic was ravaged by the Holodomor (the deliberate Soviet terror famine in the 1930s), its pre- and post-Second World War population stood at 41.7 million and 27.4 million respectively. Despite such an horrific decline, according to the UN Population Division, by 1960 the population had bounced back impressively, to 42.7 million. But that was decades ago. Now, Ukraine is no exception to the long-term population declines we see in most European nations.

I used UN data to chart the history of Ukraine’s population. The results speak for themselves. That Ukraine’s 2020 population was near-equal to its 1950 population is concerning enough. Introduce the effects of armed conflict over the past decade, and the problem appears even more dire.

In 2014, Russia annexed Crimea and fomented a forever war in the Donbas. The loss of Crimea cost Ukraine almost two million inhabitants, and a further million fled the country between 2014 and 2016 alone. The loss of these lands deprived Kyiv of a substantial proportion of its economic output.

The following eight years of war saw 10,000 civilian deaths, but these figures pale in comparison to those resulting from the recent Russian invasion. Outside of war casualties, which at very least number in the tens of thousands, Ukraine has been hit by the worst population exodus in its history.

Approximately 6.3 million refugees have fled Ukraine, the vast majority of whom have ended up in European countries. Though this figure does not necessarily represent a permanent reduction in Ukraine’s population, the question of repatriation is important to consider. The longer the war lasts, the more time refugees will have had to integrate into their host countries and build a new life for themselves. Indeed, almost a quarter of refugees are unsure if they even plan to return. It is therefore difficult to create projections for Ukraine’s population.

The longer the war lasts, the more time refugees have to integrate into their host countries. Will they ever return?

One significant outlier is the abduction of Ukrainian children to Russia proper, a process that had started before the invasion. Moscow claims that it has ‘brought’ 700,000 children into its territory since 2014. This number is widely disputed. Ukrainian authorities have verified that 20,000 children have been abducted, but this is just one figure amid a number of estimates that could well add up to over a million. As with refugees, the potential for repatriation is unclear. Even if all the children were to return, the process would likely span years and, like Ukraine, Russia, too, is suffering demographic collapse. Russia has lost around five million inhabitants since 1991, and with the war’s added death toll, this problem is sure to escalate.

Thus, by abducting Ukrainian children, Russia turns this demographic catastrophe-in-waiting into a zero-sum game in which it is the victor. For every child Ukraine loses, Russia gains another, with severe repercussions for the former.

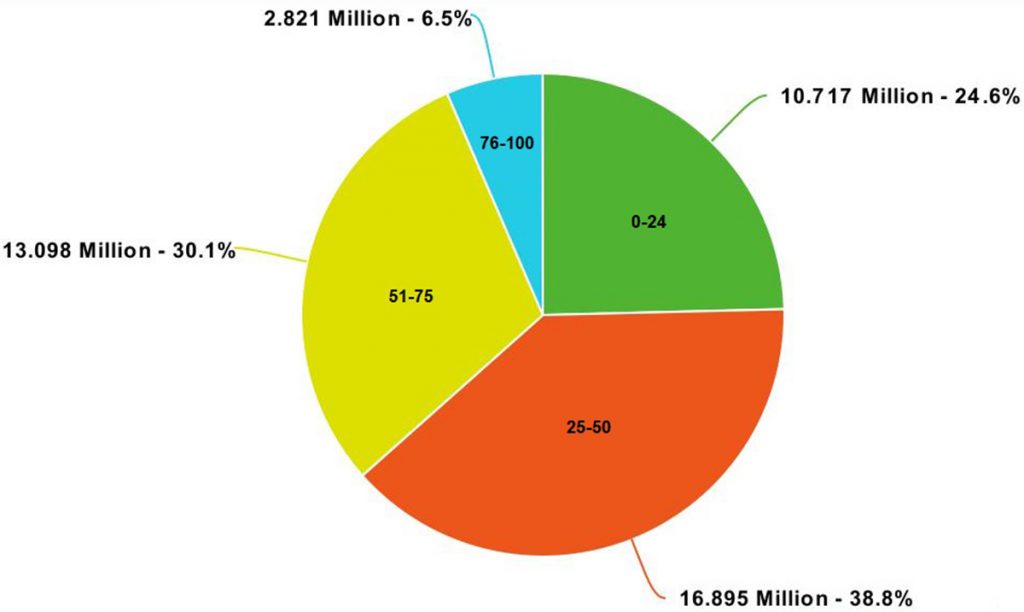

An ageing population poses long-term challenges for any country’s public services and infrastructure. Ukraine faces a compound challenge: its population is not only disproportionally composed of older people, but those who have been displaced, abducted, or killed are overwhelmingly young. The rate of repatriation for refugees is a statistical unknown, though studies have created population projections based on a variety of scenarios.

Ukraine faces a compound challenge: an ageing population combined with the displacement, abduction, or killing of its young

One study estimates that if 35% of refugees return to their homeland, the population would decline by over a third by 2040. Even a 90% return rate would still result in a 20% population decline. The likeliest outcome is a figure somewhere between these two estimates.

Regardless, Ukraine will need to accommodate a war-weary populace and rebuild its economy, including public services. In 2021, the IMF calculated Ukraine’s GDP at $199.8 billion, and predicted a sharp 20% decline by 2022. Prior to the invasion, Ukraine's per-capita earnings stood at $4,800, which already made the country one of the poorest in Europe.

Yet it would be unfair to view Ukraine’s recovery as an isolated event. Ukraine’s backers have declared initiatives to encourage private investment in the country, even during wartime. In fact, Ukraine aims to be the ‘arsenal of the free world’. With aspirations to join the European Union and the largest single market on Earth, Ukraine will have ample opportunity to attract foreign investment and kickstart its economy.

Poland, we should remember, faced a similar situation prior to EU accession. In 2004, Poland's GDP was £130 billion, but by 2013, it had swelled to £305 billion. If Poland can thrive, why not Ukraine? With its history of multiculturalism, Ukraine will also be able to accommodate immigration to bolster its population. For all the questions surrounding its impending demographic crisis, Ukraine may very well have the answers.

[…] article was originally published at The Loop (January 3, 2024) and is republished here under a Creative […]