Taking health equity seriously during the pandemic requires some minimal degree of vaccine price control. Countries around the world should make vaccine contract details public, specify a fair price, and outline how they plan to meet it, argues Felix Stein

Markets often fail during epidemics. In crisis times, essential goods and services get harder to produce, and their producers and suppliers may gain market power. This can drive up the prices of essentials to a point where they become unattainable for people in need.

During the early phase of the current pandemic, prices of masks, hand sanitiser and ventilators shot up to unprecedented heights. Over recent weeks, infections have reached record numbers in India. Medical oxygen, essential for treating acute Covid patients, is selling on Delhi’s black markets for up €1125 per cylinder: 20 times its standard price.

Vaccines are no exception. During the 2009 influenza (H1N1) pandemic, the first round of new vaccines was out of reach for most of the world’s population. High-income countries had paid pharmaceutical companies undisclosed amounts to reserve most of the global vaccine stocks.

In developing countries, vaccines against streptococcus pneumoniae have been unaffordable for decades. The bacteria cause pneumonia, which is the world's leading infectious cause of death among small children. This problem eventually led to the creation of the vaccine alliance GAVI. GAVI aims to lower the cost of vaccines by subsidising pharmaceutical companies and helping countries in need with vaccine rollouts.

In early 2020, policymakers were adamant that during this new pandemic, vaccine prices would not spiral out of control. The World Health Organization and partners launched Covax, a global vaccine buyers’ club. Provided countries agreed to buy vaccines together, Covax could promise them several benefits. These benefits included assuring them that vaccine prices would remain at 'highly competitive' levels.

But Covax has not received a significant share of globally available vaccine doses. Instead, the world’s wealthiest countries decided to outbid one another. They struck bilateral procurement deals that were more expensive than the Covax agreements, but which provided them with vaccine doses early on. When it became clear that collective procurement wasn't working well, Covax started asking rich countries to donate their excess doses.

So Covax has diminished from a global buyers’ club to merely a vaccine donation funnel. It is likely, therefore, that all countries will end up overpaying for their vaccines.

Covax has diminished from a global buyers’ club to merely a vaccine donation funnel

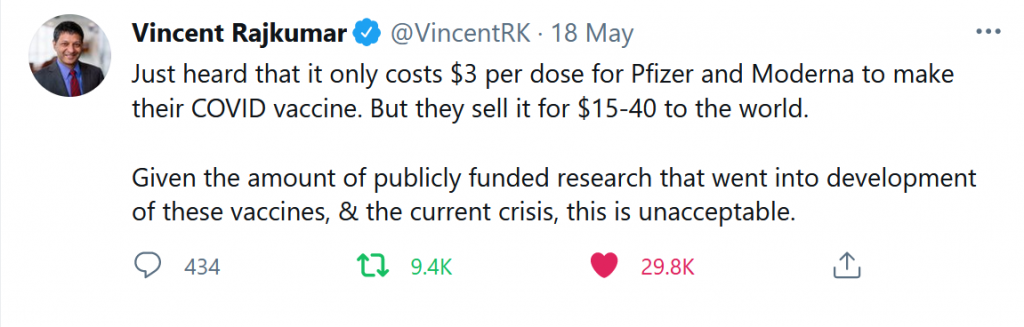

As they attempt to outbid each other on the global vaccine market, pharmaceutical companies increase their market power. We can already see this in the stark price differences between vaccines. Pfizer estimates its Covid vaccine revenues may amount to $26 billion in 2021. The company's profits will probably lie in the high 20% range, and it is taking tough stances in procurement negotiations.

The question of how much governments should pay for Covid protection is likely to remain important for years to come. Coronavirus cases are still at record highs, and barely 1% of people in low-income countries have been vaccinated. Countries privileged enough to roll out vaccines in large numbers risk needing booster shots for their citizens. What's more, Pfizer, Moderna, Johnson & Johnson and AstraZeneca have all suggested they may raise vaccine prices in the medium term.

The world’s leading Covid-19 vaccines were developed with the help of universities and public subsidies worth tens of billions of dollars. Pharmaceutical companies downplay such unprecedented public support, but it is nonetheless emphasised by public health scholars and news outlets.

people are paying twice for vaccines: once with subsidies and once when buying doses

So people are paying twice for vaccines: once with subsidies and once when buying doses. Taxpayers therefore deserve clarity about what they will get in return for subsidising the world’s most profitable industry.

The current situation is reminiscent of the 2008 financial crisis. During that last global emergency, vast sums of public money bailed out key financial institutions on both sides of the Atlantic. These institutions had become so large and interconnected that the credit they provided was considered essential to the economies in which they operated.

The size of bailouts, lavish executive pay in the financial industry, austerity politics and a lack of government and corporate accountability ended up fuelling a global politics of resentment. This resentment continues to shape the world’s political landscape today.

2020 is worse than 2008. The current crisis has claimed between 3.3 and 13 million lives. It has brought economies around the world to a standstill. To avoid the mistakes of 2008, policymakers need to negotiate fair vaccine prices. Where exactly these may lie is currently unclear.

Should vaccine pricing be based on manufacturing costs? Or should it include a profit margin to keep the pharmaceutical industry motivated during the next pandemic? Should prices reflect the social value of vaccines because only that can set the right long-term incentives? And should similar rules apply in normal times and times of crisis?

Answering these questions means contending with a pharmaceutical industry that is essential to the world, but that wields increasing power. Half-hearted participation in a global buyers’ club, combined with substantial corporate subsidies and generalised secrecy around procurement contracts, is not working. Steps in the right direction include an intellectual property waiver on Covid vaccines combined with technology transfers. But much more needs to be done.

the pharmaceutical industry is essential to the world, but it wields increasing power

Policymakers should publish all details of vaccine contracts – at least while we are still in this acute crisis phase. They may also want to insist on receiving and publishing manufacturing cost estimates from vaccine producers.

These steps would allow policymakers to engage in public discussion of how much they aim to pay for vaccines during public health emergencies, and how they hope to achieve target prices.

Only by tackling Covid vaccine pricing head on can we stop it becoming a political powder keg.

This blog is based on research funded by the Research Council of Norway, as part of the PANPREP project (grant number 301929)