What happens when political elites claim their opponents are simply mad? A proposed Bill on 'Trump Derangement Syndrome' shows how politics can spill into psychiatry. This, argues Ela Serpil Evliyaoğlu, threatens to turn dissent into pathology

On 25 March 2025, five Republican senators introduced a Bill to the State of Minnesota proposing to add Trump Derangement Syndrome (TDS) to the state's list of recognised mental illnesses. Their Bill defines TDS as a condition of paranoia, hysteria, intense hostility towards Donald Trump, and aggression towards his supporters.

This is not the first diagnosis of a 'presidential syndrome'. It is, however, the first time a president has pathologised his opponents. In 2003, conservative columnist and psychiatrist Charles Krauthammer, who helped create the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), judged that the people who claimed George W. Bush had hidden secrets about 9/11 were suffering from 'Bush Derangement Syndrome'.

During Barack Obama’s presidency, the term 'Obama Derangement Syndrome' briefly circulated, based on the mistaken belief that Obama was not born in the USA. Some even suggested that Obama's cheeseburger condiment choice – Dijon mustard, not ketchup – was another sign of 'foreignness'.

Trump Derangement Syndrome is not the first diagnosis of a 'presidential syndrome'. But what differentiates Trump is that he has embraced it – and weaponised it to his advantage

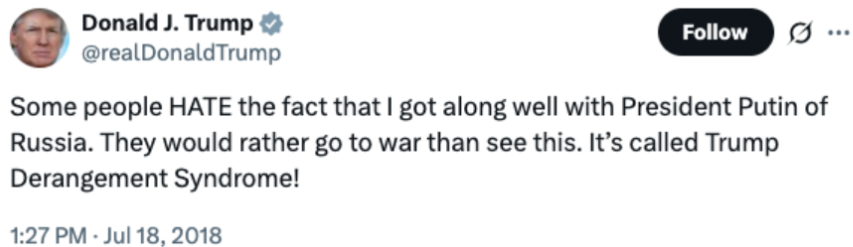

What differentiates Trump is that he and his allies have embraced the TDS label, weaponising it to their advantage. Trump claimed that those who criticised his relationship with Vladimir Putin were suffering from TDS:

Elon Musk then declared that heated Trump-related arguments with his friends revealed they too suffered with the syndrome. Trump 'diagnosed' actor Robert De Niro, Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor, and several TV hosts with the condition. After calling Trump a fascist, even John Kelly, Trump's former chief of staff, was judged (by Trump) to be suffering from TDS.

And after their dramatic falling-out in June 2025, Trump declared that Musk, too, had fallen prey to TDS.

The Musk-Trump spat shows how quickly partisan attachments can shift when elites portray former allies as deranged. Between April and June 2025, partisan views of Musk remained largely unchanged. Yet Republicans’ favourable opinions of him dropped sharply after his disagreement with Trump. Clearly, elite conflict quickly reshapes affective attachments.

Scholarship has not yet examined the effects of psychiatric labelling in politics. Decades of work on polarisation, however, point to worrying parallels. We know, for example, that:

In the past, to delegitimise dissent, political actors have applied psychiatric labels to their rivals. And even in established democracies, politicians use pathological language to portray opponents not merely as wrong, but as irrational and dangerous. Moreover, labelling opponents with a mental illness can serve as a way to detain or silence them without formal arrest, effectively stripping them of their political and legal rights.

Politicians use pathological language to portray opponents not merely as wrong, but as irrational and dangerous

It is the job of mental health experts to diagnose who is sane, who to lock up, and who to absolve from legal responsibility. When the target of such experts' diagnoses is politicians, the consequences are, of course, political.

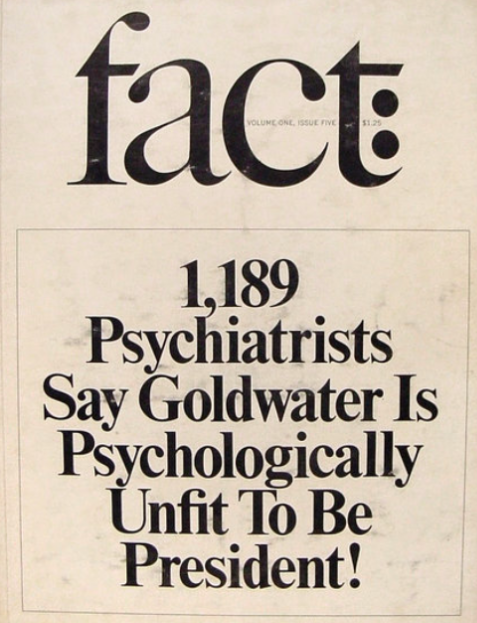

During the nomination process for Republican politician Barry Goldwater in 1964, Fact magazine surveyed 12,356 psychiatrists on his fitness for office. Of the 2,417 who responded, 1,189 deemed Goldwater unfit. They described him, variously, as 'emotionally unstable', 'immature', 'cowardly', 'grossly psychotic', 'paranoid', a 'mass murderer', 'amoral and immoral', a 'chronic schizophrenic' and a 'dangerous lunatic'.

Goldwater sued the magazine and won, though the claims still damaged his campaign. In response to the scandal, the American Psychiatric Association introduced the Goldwater rule, which banned mental health experts from evaluating public figures without personal examination.

Yet the rule has not prevented experts publicly speculating about politicians’ mental health; most notably, Donald Trump's. At the same time, no comparable ethical boundary exists to prevent politicians from deploying psychiatric labels to advance their political narratives.

The US is not alone in politicising psychiatry. To silence dissent, authoritarian regimes have long dismissed opponents as mentally deficient:

At the time of writing, nobody has yet been institutionalised for TDS, because it isn't a recognised disorder. But, worryingly, as the Minnesota Bill demonstrates, elites in the US continue to exploit the language of psychiatry for political gain. The US leads global psychiatric norms and political trends. Its politicised diagnoses thus carry serious implications.

Weaponising psychiatric language to polarise public opinion doesn't merely deepen disagreement; it signals that opponents are irrational, dangerous, or socially and politically defective. It legitimises hostility, dehumanisation and even aggression. When a political leader with enormous influence uses such language, it can normalise the same among citizens, encouraging people to pathologise one another in everyday interactions.

Weaponising psychiatric language to polarise public opinion doesn't merely deepen disagreement; it legitimises dehumanisation

It is essential that people in political life distinguish between pathology and moral or political opposition. Political actors should never respond to dissent as they would to a genuine security threat. And normalising the language of psychiatry has damaging consequences for people genuinely suffering from psychiatric disorders.

If politicians continue – with little evidence – to dismiss their opponents as mentally deficient, this exacerbates division in already polarised societies, and even risks triggering violent conflict.

TDS is an active stimulation of the amygdala resulting in triggering of the flight or fright system blocking the normal frontal lobe rational thinking process leading to a mob reaction in the political mindset promoted by nazi like zealots who fund a national campaign campaign to undermine Tump and MAGA and the constitution/ justice system

Please explain the difference between criticism of Trump (for his policies, personality…) and TDS. Or is any criticism of Trump TDS?

Because it is not an actual disorder, there are no diagnostic criteria, unlike those established for recognized mental health disorders. Recognized disorders are supported by an established body of research covering prevalence, symptomatology, effects, and progression. Since it is a mock disorder, in Trump's case for example, any criticism against him might mean TDS as he declared in some examples shared in the piece.

Trump Derangement Syndrome (TDS) began June 15, 2015 when Donald Trump announced his candidacy for president in 2016 at Trump Tower in New York City. In that moment in history, a switch was flipped in the Obama Oval Office in Washington and almost overnight TDS emerged with a viciousness rarely seen in any population in history and millions of people began exhibiting a pathological hatred of Donald Trump. Why? Because they were told to be afraid of him and what he would do as president...again.

The most amazing symptom of TDS is that it invokes a pure Pavlovian response in millions. I know many people who are Democrats. When I mention Trump, their faces instantly contort with anger, their voices drop an octave into an animal like guttural growl as they spew the foulest curse words followed by labels like fascist, racist, dictator. I love mentioning Trump to these afflicted Democrats. All I have to do is say TRUMP and they instantly go off into their madness. Pavlov would recognize that involuntary response. It would be funny if it wasn’t so tragic to see otherwise normal Americans so consumed with hate for one person and those who support him. How did they become so conditioned to act with such hatred?

Thomas Paine wrote "The slavery of fear had made men afraid to think". Fear manifests itself in hateful behaviors. Fear has been be used throughout history to control people and stifle freedom and reason? COVID anyone....anyone?

Paine believed that fear can be a form of mental slavery that prevents independent thought and critical inquiry. Those that do think and reason become a threat to those that need to control large populations with fear.

TDS may have worked backed in 2020 but it’s not working anymore and the Democrats persecution of Trump has backfired magnificently. Millions of Americans saw what they'd done and the Democrats worst nightmare came true and Trump is back in the White House despite all their best criminal efforts.

Their party's approval rating is at a historical low and they have fractured as a party with no clear leader. They have descended in chaos. We haven't seen this level of hatred since the Democrats ramped up the hatred of the first Republican president to the point where a delusional actor assassinated him. Know any delusional actors today that have TDS?

Arthur H Nimz: You ignore basics, like Trump provoking an insurrection on Jan 6, 2021. It is not irrational to think that a convicted felon is unfit to be POTUS: it is irrational to argue that TDS is a real diagnosis of anything, other than a flawed justification for your own political viewpoint.

It is perfectly rational to consider Trump's actions as counter to the US Constitution and therefore, to detest (with a passion) his re-election to the presidency (when we all know he is a convicted felon facing additional charges thereafter). It is perfectly rational to oppose (vehemently) a criminal's election to the Presidency. Only a fool would argue otherwise. People who have anger towards a violation of the spirit of our own laws do not have TDS: this is a fool's diagnosis. In fact, arguing that TDS is to blame -- instead of an understandable anger towards Trump's own actions and crimes -- is the only thing irrational in the discussion regarding TDS.

When one believes wholeheartedly what the media tells them, despite the nown or researchable facts, they appear to be a sufferer by way of delusion that permits them to persist. Then, they insist that what they have been told is the absolute truth, without any actual discernment in play. The majority of tidbits you cite, are false and proveably so.

THey claim it is a "Mock Diagnosis", which it may well have been, but currently many are showing up in mental health offices seeking therapy for many various afflictions they say are caused by their irrational hatred of Donald Trump. So I ask, Mock Doagnosis for how long?

Arthur H Nimz I believe it is a wholly manufactured illness. I am 61 and I never payed any attention to politics whatsoever. After 2017 I noticed an awful lot of hatred spewing forth from my TV, ... and it made me curious. So I engaged in what some seem to call a total waste of time because I am not an "Expert", ... Research.

I watched to the clips taken out of context, I listened to ful speeches. I jotted down claims and looked into them and found them to be false. It all started to make sense to me that these people were merely low information because they trusted the post Smith-Mundt Reformation Act media propaganda and outright lies. Now, of course, there are many showing up on therapists sofa's, comlaining that they can no longer cope with everyday life and they themselves say it is because they cannot stop thinking of how much they despise Donald Trump. What I wonder now is, at what point is it no longer considered a "Mock Diagnosis"? And will retractins be made?

Luckily for me, I do not know nor am I related to any sufferers, so I do not "Trigger" anyone, but I do see it played out from afar, as people flip ot and go into tirades yelling strings of outright falsehoods in defense of the delusion. It is not always weaponization as is claimed so often in these psychoanalytic screeds, ... sometimes it is purely observation.

What about Deranged Trump Syndrome? Is he deranged?

Any idea about treaties? How about the slave promises? Any idea how much money Trump still owes for fines and non payment of services? It’s not angry truth.

I just finished a lengthy comment on Facebook on this same subject. I hadn't read this article until after I made my comments and it's fascinating to me to see how extremely similar my comments are to the person that wrote this article. TDS might not be an official psychological diagnosis but it sure describes the craziness of those consumed by it.

I have read several articles by (alleged) psychiatrists, most of them liberals themselves who are biased, while trying to teach COPE. One thing they all have in common is claiming it is always a slur and that it has been weaponised by Trump himself, or his supporters. What all these articles mindlessly overlook, is Pure Observation. People who are not engaging whatsoever with anyone afflicted as such, but merely observing their actions, attitudes, words and reactions. It is not weaponization, it is observation of irrational behavior.

surely it is Trump's Derangement Syndrome, where the subject believes any negative reporting is Fake news, where anybody who isn't in his control is a dangerous liability requiring social ridicule and replacement with a sycophant, where media decay provides the necessary nutrients to thrive.

Perhaps, in the future, when Mr Trump is gone, so will the syndrome? Will it morph into JDDS or EMDS?

TDS is already covered under DSM-5-TR code 300.29 as Cacophobia. It affects many who just look at him.

People with TDS don't live in reality. They believe the world is much different and more dangerous than it is. TRUMP GETS REALITY and understands how the world actually works. TDS sufferers believe incredible lies, living in a false reality stemming from ignorance leading to paranoia/derangement. Consequently they (incorrectly) think everything he does is WRONG. It's NOT.