The way people think the economy works shapes public opinion towards progressive taxation. But the 'tax the rich' crowd don't neglect economic efficiency, observes Lucy Barnes

The politics of progressive taxation presents a paradox. Polling on whether taxes on the rich should be increased returns supermajorities in favour, yet the recent direction of travel has generally been away from high top tax rates. Those defending this shift often use a simple description of the economy to do so. High rates on top incomes, they say, thwart economic progress. However, the public continues to support progressivity. Either this message is not getting through, or there's a link missing between that idea and views on taxation.

Public opinion favours high taxation rates on top incomes – despite the argument that this thwarts economic progress

Systematically mapping how people think the economy works points towards the first of these two explanations. A positive-sum mentality that neglects distributive concerns does predict lower support for progressivity. But it is not widely shared. The more common view is not a naive zero-sum mentality. Instead, it's one that remains attentive to questions of growing the pie and sharing it equally.

Understandably, people's interests and values structure their attitudes towards taxing the rich. Those who are themselves richer tend, on average, to be less supportive of large tax burdens on high incomes. Similarly, people who place a high moral value on equality tend to support higher taxes on the rich.

But it should be equally unsurprising that descriptive ideas about how the economic world works also have an impact on the policies people advocate. No matter how strong my egalitarianism, nor how low my income, I will not support progressive taxation if I believe it will stifle all economic activity or lead to massive evasion by the rich.

There are many ways to characterise public thinking about the economy. When it comes to the question of progressive tax attitudes, a useful way to do so is to distinguish between zero-sum thinking – the 'fixed pie' mindset – and positive-sum thinking – the 'growing pie' mindset.

When it comes to progressive tax attitudes, a useful way to characterise public thinking is to distinguish between zero-sum thinking – the 'fixed pie' mindset – and positive-sum thinking – the 'growing pie' mindset

If the pie is fixed, then tax policy is simply about the fair redistribution of resources. But if there is scope for the economic pie to grow, tax policy decisions must also take into account the possibility that they affect the size of the pie. The Laffer Curve theory holds that high levels of taxation on the rich disincentivise economic effort and activity, and so shrink the overall pie. In the tax policy context, the zero-sum mindset does not recognise these implications.

In a recent paper, I describe the links between zero- and positive-sum descriptive thinking and people's preferences regarding the level of tax paid by high-income earners in five rich countries. These countries were the United States, United Kingdom, France, Germany and Denmark.

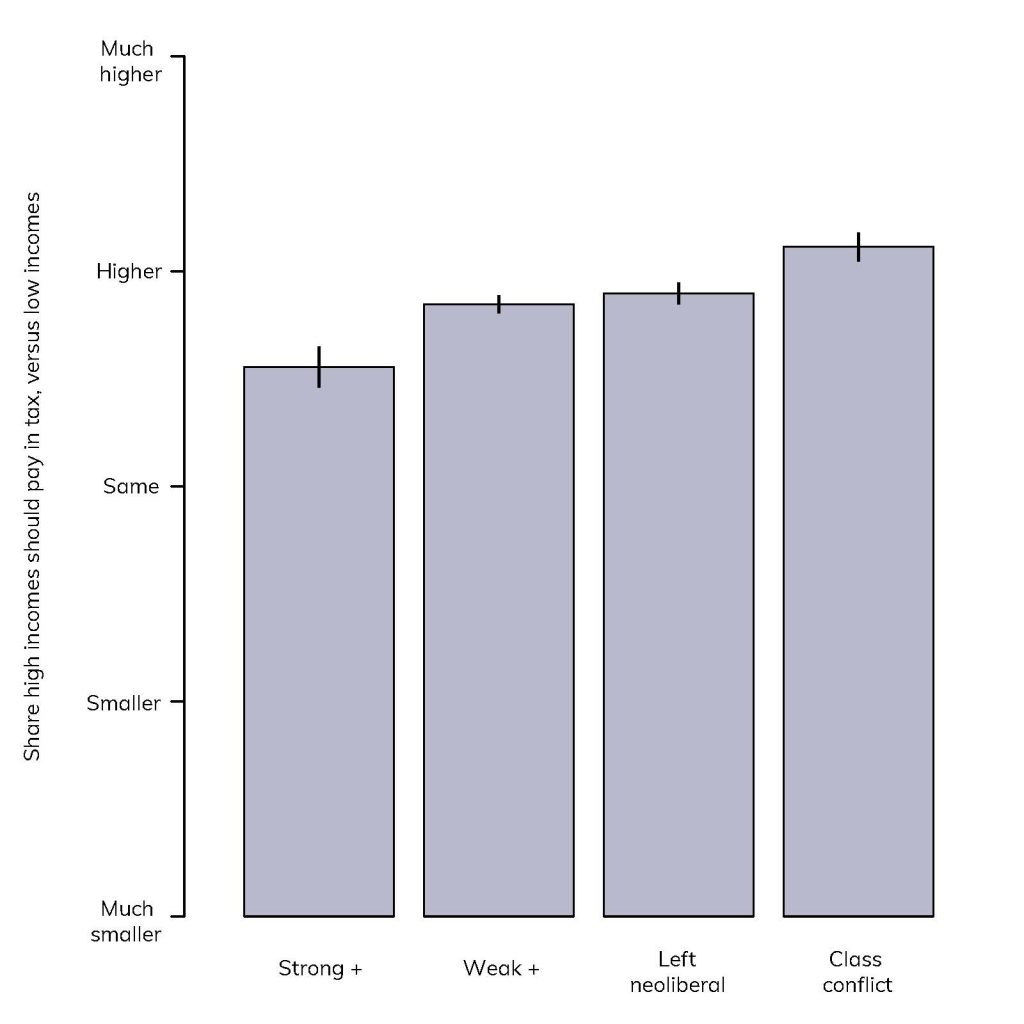

The chart shows the average response to the question of whether the share of income paid in tax by high-income earners should be a smaller or larger share of their income than that paid by those with low incomes. I have split them into four groups of people, categorised by their descriptive beliefs in a zero-sum economy.

In particular, in the first column, those who hold a strongly positive-sum perception propose the smallest differential in tax rates. Their average response is about halfway between the belief that the rich should pay a larger share, and that they should pay the same share as low-income earners. This is a small group, though: around 7% of the survey respondents.

The second column, a group who affirm the growing-pie precepts but less emphatically, are clearly distinct. They make up 29% of the sample and gravitate towards the 'larger' share as their average preference.

The averages in the chart do not take into account underlying differences in the type of people in each group. For instance, we might think that only high-income people see the world as positive-sum. Therefore, the difference in the figure is due to that feature rather than the descriptive thinking of the group itself. But the gaps between groups remain when we compare people who differ in their economic thinking between people who are similar in terms of the most obvious of these factors.

On the bottom right of the chart, we find the labels 'left neoliberal' and 'class conflict', rather than weak and strong zero-sum. What's that about?

It turns out that people who give consistently zero-sum descriptions of the economy are pretty hard to find. In particular, zero-sum views of the labour market were rare. Very few disagreed with the idea that economic policy needs to focus on increasing the size of the pie. Instead, the groups that deviate from weaker or stronger endorsement of a positive-sum view do so through a more emphatic concern for distribution.

People who do not endorse a positive-sum view show an attentiveness to indirect effects and distributive issues

Left neoliberals endorse positive-sum goals and labour market dynamics. However, they agree that the success of the rich comes at the expense of others, and that policy should aim at fair distribution. The class conflict group, meanwhile, strongly agree that the rich succeed at the expense of others. They strongly disagree with the idea that the rich getting richer improves aggregate conditions.

These constellations of descriptive beliefs cannot be said to be a zero-sum mentality. Instead, they show an attentiveness to indirect effects and a need for growth. Simultaneously, they show an ongoing emphasis on distributive issues. Both of these groups prefer much more progressive tax structures than the strong positive-sum group.

Beliefs about how the economy works, not just interests and values, shape public preferences and opinion over taxation. But support for high taxes on the rich is not driven by inattention to efficiency concerns. Inattention to distributive effects is, instead, a distinguishing feature of opponents of progressive taxation.