Have you ever tried to change your diet based on new information, perhaps after reading about the environmental benefits of plant-based eating or the health risks associated with processed meat –– only to find yourself slipping back into old habits? If so, you are not alone, writes Carolin Zorell

Widely available factual information alone often fails to change people's food choices. As researchers, my colleagues Nicklas Neuman, Ansung Kim and I wanted to understand why. We also wanted to find out whether social cues, such as learning that others around us are shifting their diets, might be more effective. This is not just a question of individual choice; it is a fundamental issue of socio-political relevance.

Governments the world over are striving for net-zero emissions, tackling obesity and malnutrition, and confronting the role of food systems as major polluters. As they do so, however, they are coming under increasing pressure to design effective policies that drive sustainable dietary shifts. But what actually works? Do people change their diets when presented with compelling facts, or when they see others changing? Or do we need more direct government intervention?

In our recent research, published in the Journal of Nutritional Science, we conducted a study over four months. Our research tested an intervention with randomly assigned groups (a so-called randomised controlled trial), to investigate how different types of information influence food consumption. We divided the 237 adult participants from Sweden into three groups:

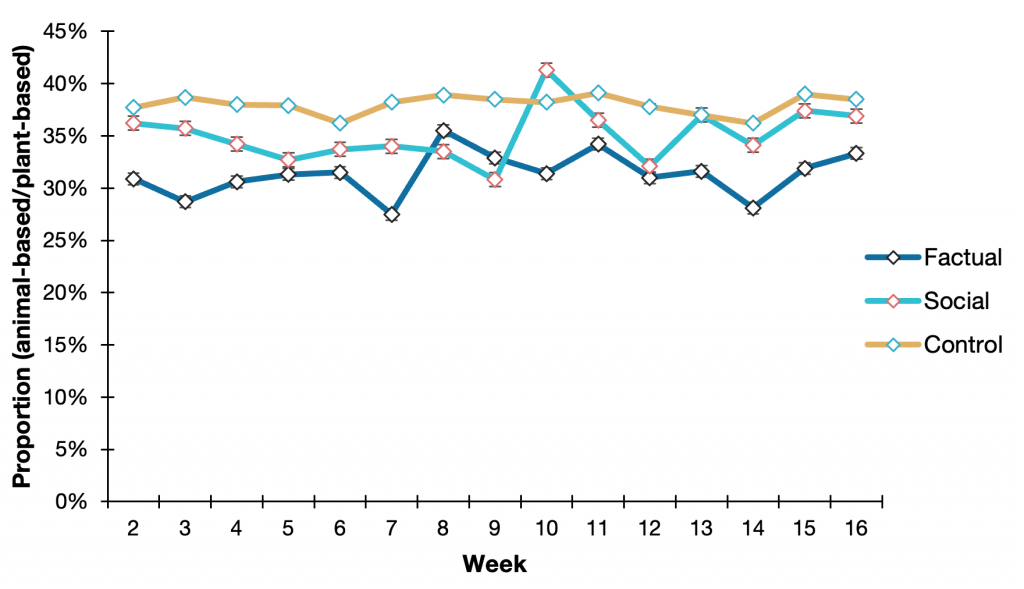

What we found was striking. While those exposed to social information showed a slight decrease in animal-based food consumption, the overall impact on eating habits was limited (see the graph below). Even when armed with compelling facts or made aware that others were changing their diets, most participants did not significantly alter their food choices in the long term.

Even when study participants were given compelling facts about the benefits of plant-based food, they did not significantly alter their food choices

This raises important questions for policy-makers and advocates working on food sustainability and public health. If neither factual nor social cues are strong enough to drive lasting dietary change, what does? Prior research suggests that eating behaviours are deeply embedded in social and environmental contexts, including structures of power, governance, and economic incentives. People are influenced by what is available, what is affordable, and the habits of those closest to them. Institutional factors such as subsidies, taxation, and food marketing regulations also shape food choices.

To force changes in individuals' food choices, policy-makers must alter the structural conditions in which those choices are made

This means that if policy-makers want to influence food behaviour to encourage healthier and environmentally sustainable diets, simply providing information, whether factual or socially framed, is unlikely to be enough on its own. Policy-makers must alter the structural conditions in which choices are made. This resonates with regulatory approaches in public health policy, where direct interventions like tobacco taxes and sugary drink bans have proven more successful than awareness campaigns.

Strategies aimed at shifting dietary behaviours must go beyond information campaigns and voluntary behavioural change, and consider harder policy interventions:

Food policy is deeply political. It intersects with ideological debates over individual choice and responsibility versus government intervention, the role of corporate influence in shaping dietary habits, and the balance between cultural traditions and sustainability goals. Policy-makers must navigate competing interests: environmental advocates pushing for stronger regulations, food industry lobbies resisting taxation, and citizens wary of government overreach.

Those developing food policy must navigate the competing interests of environmental advocates, food industry lobbies, and citizens wary of government overreach

If governments are serious about tackling public health and environmental sustainability, they need to acknowledge the limits of persuasion and start focusing on structural solutions. Our study is just one piece of this larger puzzle, but it adds to a growing body of evidence suggesting that behavioural change requires more than just good arguments – it requires political will, institutional reform, and a policy landscape that makes better choices the easier ones for everyone.