It is now a year since the Greens formed an unprecedented government coalition with the centre-right in Austria. There are lessons for Green parties elsewhere in Europe, writes Marcus How

The coalition formed between the Greens and the People’s Party (ÖVP) in Austria in January 2020 is the first of its kind on the national level in Europe, combining the centre-right with the ecological left in an exclusive two-party marriage.

It was formed on the back of a snap election caused by the 'Ibizagate' corruption scandal and the collapse of the governing coalition between Chancellor Sebastian Kurz’s ÖVP and the far-right Freedom Party (FPÖ).

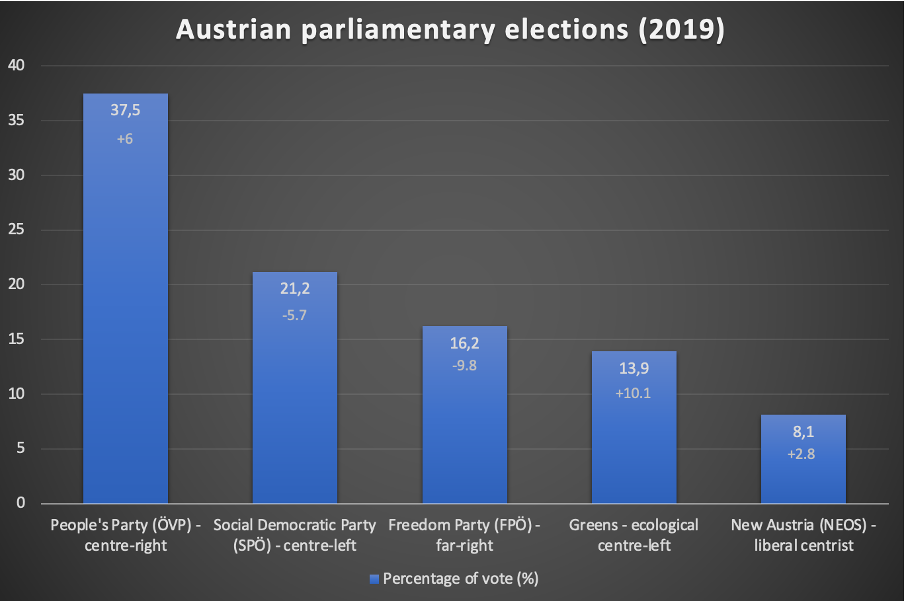

Until then, the Greens had been languishing in the doldrums, with ruddy-faced party veteran Werner Kogler taking the reins of a divided party that in 2017 had failed to secure parliamentary representation for the first time since the 1980s. Kogler restored internal discipline but, ahead of the snap election in 2019, was aided by growing public awareness of climate change as well as corruption. Indeed, the Greens saw their vote rise from a measly 3.8% to a record 14%.

Meanwhile, the ÖVP had emerged as the clear victor, winning 37.5% of the vote. President Alexander Van der Bellen – himself a former leader of the Greens – lobbied hard for the two winners of the election to join forces.

This was a tall order because the two parties are politically so disparate. Under the personalised, PR-savvy leadership of Sebastian Kurz, the ÖVP had subsumed many of the themes of the FPÖ – migration, for one – and with it, many of their voters. The Greens, meanwhile, identify with exactly the opposite.

The solution to this impasse was to negotiate a coalition based on the principle of cohabitation, rather than a common vision; or, what Kurz and Kogler described as 'the best of two worlds.' In other words, the two parties were to be granted ownership over their respective policy briefs in exchange for circumspection on issues that fall outside of these ringfences. For their part, the Greens secured four cabinet portfolios: health, justice, culture – and a supersized hybrid of climate, energy and infrastructure.

As it happened, the Covid-19 pandemic changed the nature of this arrangement, which has in any case proven a poisoned chalice for the Greens. On policy, the ÖVP has, for example, refused to take up asylum-seeking minors from Greece and, following a jihadist terrorist attack in November, pushed through legislation that allows for monitoring of Muslim organisations.

a coalition based on the principle of cohabitation, rather than a common vision

The Greens have kept their peace, with Kogler and parliamentary faction leader, Sigi Maurer, maintaining the support of the party’s delegates. Yet the ÖVP has few qualms about undermining its coalition partner, not least through its relentless comms operation. Unlike the Greens, Kurz and the ÖVP are not squeamish about exploiting the Austrian boulevard media model, which effectively offers favourable coverage in exchange for the state advertising contracts extended by ministries.

As such, the ÖVP has been able to brief against individual ministers. The health minister, Rudi Anschober, enjoyed higher approval ratings than Kurz at one point – to which the ÖVP seemingly responded by reducing Anschober’s ministerial role to that of a glorified manager, while often contradicting him. After a terrorist attack in November, Interior Minister Karl Nehammer blamed the Justice Ministry – led by his Green colleague, Alma Zadic – for allowing the future perpetrator early release from prison, omitting to mention that the ministry had been controlled by the ÖVP at the time.

Politically, the Greens are in a strange place. Their ministers’ approval ratings reveal them as among the more popular in the coalition. They have cashed in several policy successes, demonstrating a grasp of realpolitik. Alma Zadic implemented some politically difficult reforms of the Justice Ministry, enabling greater separation of responsibilities, but disrupting ÖVP-aligned networks in the process. The Greens secured a sharp increase in humanitarian funds in response to the ÖVP refusal to take up asylum-seeking minors. Soon they will be able to channel large amounts of earmarked stimulus funds into green projects.

Yet this is insufficient. The polls are not yet cause for alarm, but public discourse suggests that there is increasing discontent with the Greens, not least among left-liberal voters. For now, a deeper slide is being prevented by the internal crisis in which the Social Democratic Party (SPÖ) finds itself.

Part of the reasoning for cohabiting with Kurz in the first place was to act as a bulwark against the FPÖ

Although this gives the Greens more space in which to throw their weight around, the leadership is unlikely to destabilise the coalition. Part of the reasoning for cohabiting with Kurz in the first place was to act as a bulwark against the FPÖ. If the coalition collapses, Kurz may form a minority government or call new elections. It may be a bluff, but both scenarios threaten the Greens’ relevance. Better to chalk up some wins and ride out the pandemic than fight an uphill battle.

But the current situation is unsustainable. On 25 January, the police detained three schoolchildren with illegal migrant status in order to bring them to a deportation centre. The Greens, their base restive, condemned the action, but beside the ÖVP their objections ring hollow.

The position of the Greens in Austria is unenviable, but it provides a lesson to its sister parties elsewhere in Europe, not least Germany where the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) and Greens are expected to form a coalition.

Coalitions invariably necessitate policy trade-offs that tend to be especially painful for junior parties. Focusing exclusively on core policies is a way around this but, equally, this is not an excuse to disengage. Publicly drawing lines is therefore necessary, if risky. Empty threats serve only to hurt the party that makes them. At some point, the Austrian Greens will need to call Kurz’s bluff.