Romania’s Constitutional Court has annulled the country's recent presidential elections, alleging Russian meddling. John Chin, Mirren Hibbert and Staten Rector argue that its decision raises profound questions about the legacy of Romania’s 1989 revolution, and the future of democracy and Western influence in this frontline state

On 6 December 2024, Romania’s Constitutional Court, citing newly declassified disclosures of ongoing Russian electoral meddling, annulled the presidential election just two days before second-round voting was due to take place. The first-round elections had catapulted the pro-Russian populist candidate Călin Georgescu into first place ahead of the pro-European reformist candidate Elena Lasconi. The court declared these elections would have to be re-run.

Romania’s current political crisis began to deepen in the month of the 35th anniversary of the 1989 revolution. Were Winston Churchill alive today, he might again decry Russian efforts to exert 'sharp power' and make its influence felt from Belarus to Bucharest.

Some claim a new Cold War is dawning, pitting the West against an anti-liberal 'axis of upheaval'. If so, Romania will be critical to making Eurasia safe for democracy.

Romania was an unlikely site of revolution in 1989. Unlike Poland or Hungary, the country's regime faced little opposition from reformists or liberals, who kept their heads down for fear of retribution from a police state. Nicolae Ceaușescu, Romania’s personalist dictator, had held power for 34 years, and had managed to achieve some autonomy from the Soviet Union. In March 1989, Ceaușescu's regime paid off the substantial foreign debts it had accrued during the 1970s.

Yet Romania’s autocratic stability was a product of preference falsification, not legitimacy. By 1989, the economy was on its knees. Austerity policies led to declining living standards and shortages of basic necessities. Meanwhile, across Eastern Europe, other communist dominoes were falling.

The trigger for Romania’s revolutionary unrest, however, came from an unlikely place – Timișoara – and for an unlikely reason. On 15 December, the forced eviction of outspoken Hungarian Reform pastor László Tőkés triggered the first protests by Tőkés' parishioners. On 17 December, security forces opened fire, killing 100 protestors.

In 1989, the state's attempts at repression backfired, and a small protest movement soon exploded into a nationwide anti-communist campaign

But the state's attempts at repression backfired, and this small movement soon exploded into a nationwide anti-communist campaign. On 21 December, while Ceaușescu delivered a speech, angry crowds began to boo, and eventually stormed the building, forcing him and his wife to flee. By 22 December, hundreds of thousands of Romanians had joined in the protest. Romania’s security forces split; the more personalised Securitate fired on protestors and clashed with defecting army units that sided with the revolution.

Bucharest descended into chaos. Defectors led by former Romanian president Ion Iliescu and commanded by army General Nicolae Militaru coalesced under the banner of the National Salvation Front (FSN) to fill the vacuum. Nicolae and Elena Ceaușescu were executed on 25 December 1989.

Violent transitions from personalist dictatorship rarely lead to democracy, and many post-communist states failed to transition to or consolidate democracy. Yet, after the Cold War, Romania did have some success in establishing democracy and capitalist development.

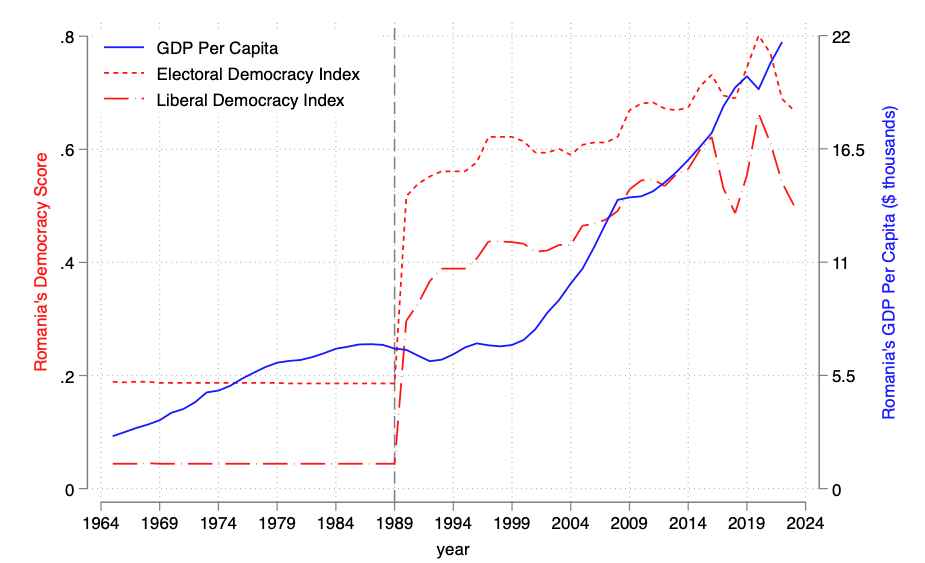

According to V-Dem data, between 1990 and 1992, Romania’s transition to electoral democracy was swift. Iliescu won the 1990 and 1992 elections, and in 1991 a constituent assembly crafted a new constitution. The FSN morphed into the Social Democratic Party (PSD), which became one of Romania’s leading parties. Several peaceful transitions of power have taken place since 1996, and after the stalled economic growth of the 1990s, since the 2000s, the economy is rallying once again (see figure below).

After Romania joined NATO and the EU, the quality of democracy in the country improved, but since 2021, Romania has undergone a second phase of democratic erosion

Romania joined NATO in 2004 and the European Union in 2007, and for several years the quality of democracy improved. However, per V-Dem data, the country has experienced two recent waves of democratic backsliding. From 2016–2018, the ruling PSD politicised anti-corruption, adopted populist rhetoric, and challenged judicial independence. After a brief period of re-democratisation in 2019–2020 under a new government, since 2021 Romania has undergone a second phase of democratic erosion.

Geopolitical tensions loom large in Romanian politics. The war in Ukraine has strengthened establishment parties’ commitment to European integration. In March 2024, construction began in Romania on what is slated to become NATO’s largest European base. In December, Romania became a full member of the Schengen zone, allowing free travel with the rest of Europe.

While war in Ukraine has strengthened establishment parties' commitment to European integration, anti-European sentiment is also on the rise

But anti-European and anti-establishment sentiment is also on the rise. In the annulled presidential elections, Georgescu, running as a 'Romania first' independent, shocked the establishment. This pro-Russian candidate – who vowed to end Ukraine aid and called for 'Russian wisdom' in shaping foreign policy – scored only single-digits in pre-election polls. In this month’s parliamentary elections, far-right nationalists also made huge gains.

Romania’s democracy and pro-Western orientation are being tested by internal polarisation aided by Russian disinformation operations. On TikTok, Georgescu was elevated by paid promotion and recommended algorithms.

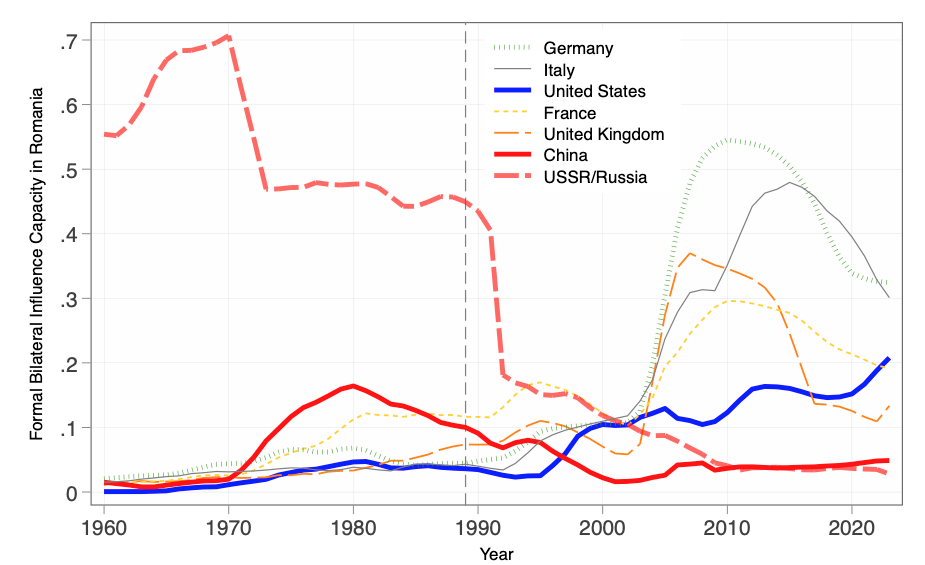

Attempts to assert Russian influence in Romania echo the Cold War but fly in the face of post-Cold War trends. Data on formal bilateral influence capacity show that the era of the Soviets/Russians being the dominant foreign influence in Romania ended after 1991. Romania’s economic and security ties are much stronger with the rest of Europe than with Russia or China, and US influence has increased steadily since the mid-1990s. A recent poll suggests large majorities of Romanians still support membership of the EU and NATO.

The US (non-)response, tolerating anti-democratic behaviour in the name of defending the 'free world' amid competition with an autocratic great power, also echoes the Cold War. US Secretary of State Antony Blinken has drawn parallels with similar incidents of Russian partisan electoral interference in Moldova and Georgia. But using constitutional hardball to overturn alleged election interference may only destabilise democracy further.

For now, Romania’s pro-Western parties have agreed to form a majority government and shut out far-right parties. Romania, though, is once again a Cold War frontline state living in the shadow of Europe and Russia. It is a canary in the coalmine of Cold War 2.0.