The people of Kazakhstan are still grappling with the toxic legacy of twentieth-century Soviet nuclear tests. Marzhan Nurzhan examines nuclear identity and decoloniality in Kazakhstan's atomic past, through the medium of visual art

In the late 1940s, the USSR picked the Kazakh steppe as the testing ground for its first nuclear weapons programme. Claiming the area was ‘uninhabited’ or ‘sparsely populated’, the Soviets chose to disregard the presence of local communities. Nuclear experiments took place in complete secrecy, and many locals remained unaware that they had been used as test subjects.

Between 1949 and 1989, at the Semipalatinsk test site in northeast Kazakhstan, the USSR carried out a quarter of the world’s nuclear explosions. Their experiments exposed around 1.5 million people to harmful ionised radiation. The result was widespread environmental contamination, and enduring damage to the health and livelihoods of local people.

During the Cold War, the USSR entered into a fierce arms race with the US. Experiments at Semipalatinsk site empowered the Soviets to upgrade their nuclear arsenal. Soviet militarism became nuclear colonisation: Moscow was realising its ambitions at the expense of the Kazakh landscape and the lives of Kazakh people. Magdalena Stawkowski describes how, at Semipalatinsk nuclear test site, ‘science, technology, Soviet Cold War militarism, and human biology intersected’ in an experimental landscape.

In 1989, Kazakhs rose up against Soviet nuclear colonisation. Organising as the Nevada-Semipalatinsk anti-nuclear movement, locals staged peaceful protests calling for an end to extraction, concealment of the truth, and the devastating consequences of nuclear tests. Protesters demanded immediate closure of the Semipalatinsk test site. Civic pressure eventually helped put an end to the tests, and Kazakhstan's government officially shut down the site in 1991.

Scholars have coined the term 'nuclear colonisation' to describe how powerful states test, develop and maintain nuclear weapons on the bodies and lands of marginalised populations. A University of Washington report defines nuclear colonisation as 'the process of acknowledging, intervening, and disrupting narratives and actions reinforcing nuclear violence'.

The movement towards 'nuclear decolonisation' recognises this harm, and takes steps to heal the damage. The same report describes decolonisation as actions that 'disrupt colonial structures and contribute to the repair of colonial harms'. Nuclear decolonisation can take the form of peaceful protest, activism, calls for nuclear justice, and expression through art and storytelling.

Dealing with trauma through the medium of art is helping the people of Kazakhstan resist colonialism, reclaim agency, and reimagine their radioactive legacy

Recent research on decolonial practices in Kazakhstan has focused on resistance to nuclear colonisation and imperialism. But another study, on artistic reactions to nuclear testing at the Semipalatinsk site, remains less widely analysed. Here, I show how art can help resist colonialism, reclaim agency, and reimagine Kazakhstan’s radioactive legacy.

One victim of Soviet-era nuclear tests is artist Karipbek Kuyukov, born in 1968 in Yegyndybulak, 100km from Semipalatinsk. Kuyukov's mother had been exposed to heavy doses of ionised radiation. As a result, her baby was born without arms. Kuyukov now draws and paints using his mouth and toes.

Art can challenge accepted ideas — making it a powerful tool for understanding and resisting colonial history. Kuyukov's paintings show how people, cultural heritage, and nuclear history are connected. He intends them to provoke an emotional reaction; 'to showcase the tragedy of the atomic legacy and reach [people's] consciousness'. His art offers new, culturally rooted ways to remember and deal with historical trauma.

Kuyukov is also a veteran of the anti-nuclear Nevada-Semipalatinsk movement, and an Honorary Ambassador of the ATOM Project. In 2024, the Kazakh Foreign Ministry appointed him a Goodwill Ambassador.

In Kazakhstan, stigma is still attached to people harmed by exposure to dangerous radiation. Tackling this topic remains a challenge

Kuyukov has dedicated his life to painting and activism, raising awareness of the environmental and human devastation caused by nuclear weapons testing. His works draw deeply on personal experience, often visualising unhealed traumas from the Soviet nuclear-test era. Tackling the topic remains a challenge, because in Kazakhstan, stigma is still attached to afflicted people.

Here, I present four Kuyukov works depicting varied scenery and characters. They also contain elements of traditional Kazakh culture, including a yurt, kiiz üi; ornaments, oyu-örnek; cattle and horses; the national instrument dombyra; and a baby's cradle, besik.

Resilience in the face of the bomb: a mother, seated on a carpet and surrounded by traditional ornaments, rocks her baby's cradle. In the background, a bomb explodes on the Kazakh steppe.

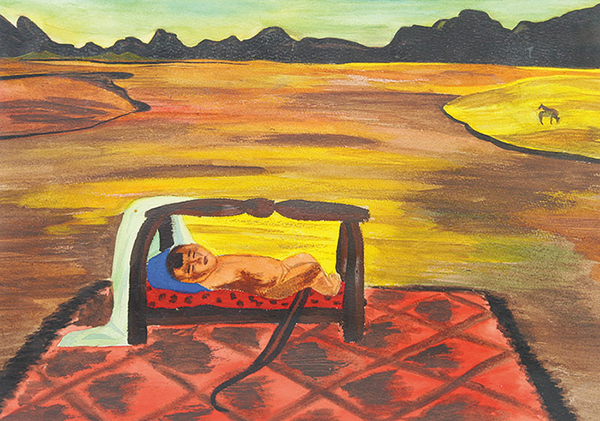

Self-portrait as a baby in a Kazakh cradle on the Steppe. Two atomic craters, the right-hand one with horses, represent the vulnerability of human beings and the natural world.

An atomic bomb explodes, destroying a family's yurt. The mother cradles a baby, protecting it from the blast.

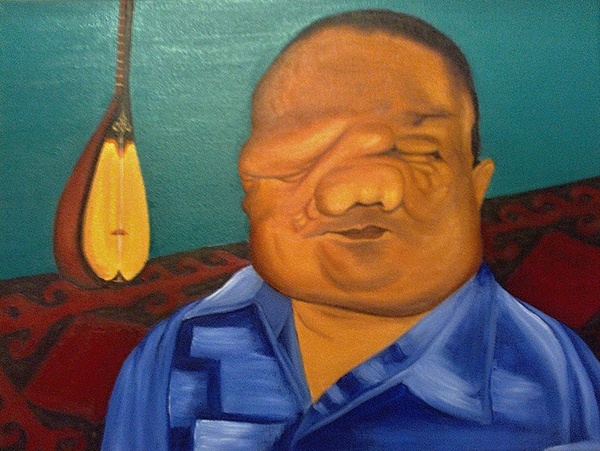

Berik Syzdykov, a friend of the painter is also a victim of radiation, whose eyes are not visible in his heavily disfigured face. In the background, on a Kazakh patterned carpet, is the dombyra Syzdykov played.

Since its independence, Kazakhstan has championed, and advocated for, nuclear disarmament. The country has removed its nuclear arsenal, and fully adopted non-proliferation norms and treaties. Kazakhstan has pushed strongly for a global ban on nuclear weapons. It was one of the first fifty countries to sign and ratify the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW).

Since gaining independence in 1991, Kazakhstan has removed its nuclear arsenal, and fully adopted non-proliferation norms and treaties

The Third Meeting of States Parties to the TPNW took place at UN headquarters in March 2025, under the presidency of Kazakhstan. Kuyukov addressed the meeting, presenting his artworks, reading survivors’ testimonies, and demanding justice for nuclear test victims.

The toxic fallout from historic atomic tests means that public antagonism to nuclear power still lingers in Kazakhstan. Despite this, in a 2024 referendum, the majority of Kazakhstan’s population backed a proposal to build the country’s first nuclear power plant. On 16 June 2025, the government of Kazakhstan announced it had chosen the Russian state firm Rosatom, along with the Chinese National Nuclear Corporation, to lead the project.

Kazakh survivors of Soviet tests are now seeking reparations from Russia. Meanwhile, a new generation of young activists, including the Steppe Organisation for Peace initiative and the Qazaq Nuclear Frontline Coalition, have joined forces to pursue nuclear justice.

Kazakhstan continues the long process of overcoming its pernicious Soviet legacy. At the time of writing, Russia’s hold on Ukraine’s Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant is an alarming reminder that nuclear security threats – this time in the form of piracy – are not yet consigned to history.