Mirko Crulli questions the cliché that populism thrives only in ‘left-behind’ places. While populist parties, especially radical-right ones, are typically stronger in peripheral and low-density areas, populist strongholds exist within thriving cities. Several factors, including composition, context, and place-based identities, help explain geographic variations in populist support across contemporary Europe

The ongoing rise of populism has redrawn political geography. Nonetheless, accounts of the geography of ‘discontent’ and populism have only gained momentum since Brexit and the election of Donald Trump. Support from voters in peripheral-rural areas played a huge part in both these events. Due to this delayed emergence of literature on the ‘places of populism’, much research has carried out national- and individual-level analyses of the populist wave. Yet this glosses over the significance of places themselves. Indeed, a 2019 editorial in Political Geography lamented the absence of ‘substantive debate about the place of populism in geography’ and ‘how populism should be spatially thought through’.

Happily, scholarship is paying renewed attention to local contexts in studying populist and radical-right politics. There is thus now consensus around the thesis of the places ‘left-behind’ or ‘that don’t matter’. This suggests that populist victories represent a retaliation by lagging-behind towns and regions, which feel neglected by policymakers amid socioeconomic changes brought on by globalisation. The polar opposite of such declining populist-supporting places would be large, vibrant cities, which research depicts as being immune to populism. Therefore, in the 'places left-behind' thesis, the cleavage between populist and pluralist-libertarian orientations corresponds to a territorial fracture. Booming metropolises are pitted against struggling rural or small-town areas.

In the 'places left-behind' thesis, the cleavage between populist and pluralist-libertarian orientations corresponds to a territorial fracture: booming metropolises versus struggling rural or small-town areas

This thesis is appealing, has overall validity, and a major merit: it brings geography into the equation explaining populist success. However, accepting the thesis in toto may lead us to adopt a stereotypical definition of the phenomenon. In fact, the ‘left-behind’ thesis seems to ignore several factors that make the territorial character of contemporary European populism much more complex.

First, populists are successful in certain rural areas but not in others. The same goes for cities. Secondly, most large metropolises encompass not only urban but also suburban/peri-urban and low-density environments. Indeed, globalisation, de-industrialisation and post-industrialisation eroded the historically rigid urban-rural cleavage.

It's no good focusing solely on the division between dynamic ‘big cities’ and lagging ‘non-cities’. A metropolis is not a monolithic territorial unit

In this regard, some authors claim that the mix of proximity and separateness of peri-urbans from proper urban centres can fuel resentment towards the latter. This could explain why some populist parties are strong in such areas, or the ‘suburbanisation’ of radical-right populism. Research also suggests that suburban dwellers support populist parties to ‘reclaim urban space for daily use and as a defensive strategy in view of metropolitan change’. In short, focusing solely on the division between dynamic ‘big cities’ and lagging ‘non-cities’ is inadequate, because a metropolis is not a monolithic territorial unit.

The latest wave of the European Social Survey (ESS) can help explore the nuanced geographical patterns in populist and radical-right support. This dataset comprises questions on populist and radical-right (nativist and authoritarian) attitudes, and on respondents’ vote and residency type.

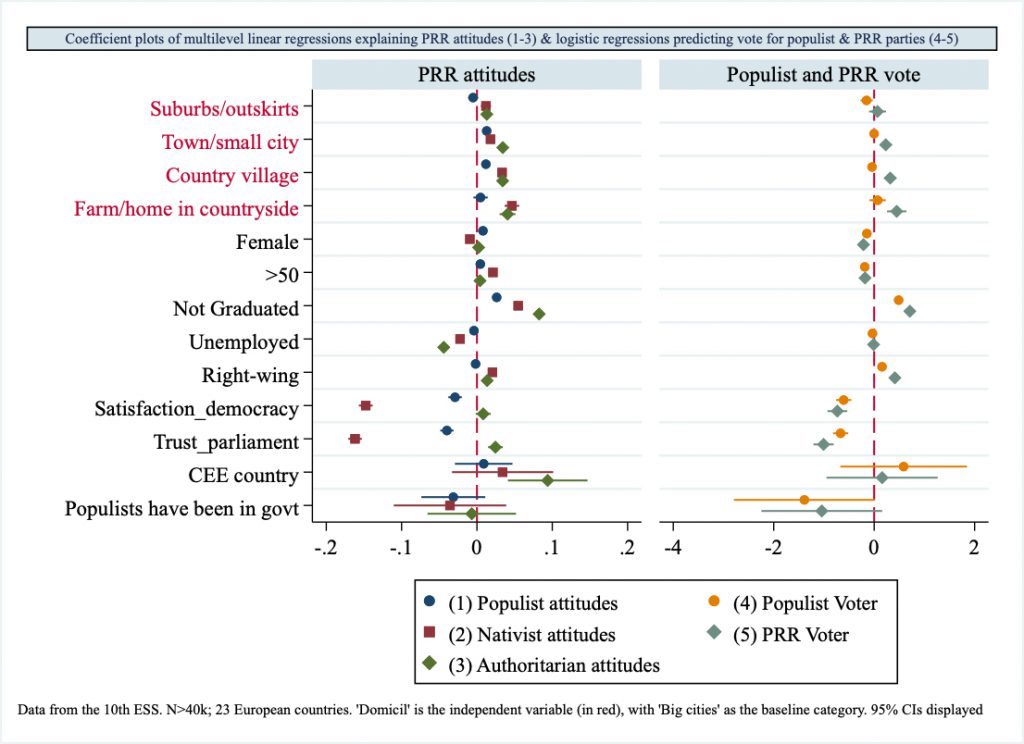

Using the ESS, I conducted a regression analysis, displayed in the figure below. My analysis revealed that the distinction between cities and suburban-rural areas in populist attitudes and votes is not clear-cut. Populism exists across various types of residences, and there is no continuum running from alleged less-populist cities to alleged more-populist urban or rural peripheries.

However, a greater divide emerged concerning radical-right attitudes and votes. This divide becomes stronger the more we move toward less densely populated places. In short, radical-right orientations appear to have a much stronger association with territorial rifts compared with populist ones.

Following the ‘places that don’t matter’ leitmotiv, the focus in populism geography literature has mostly been on regional and city-towns/villages comparisons. Scholarship has paid less attention to how populist support varies within municipalities. But recent works relying on fine-grained electoral data emphasise that populist pockets exist within clearly not-left-behind metropolises, including Vienna and Milan. For instance, a study on the ‘urban roots’ of populism found that a populist party has won general elections at least once in roughly 35%, 55%, and 80% of the precincts in Milan, Turin, and Rome, respectively.

What are the mechanisms driving this geographic heterogeneity in populist support? Two classical explanations relate to compositional and contextual effects. Compositional effects assume that ‘the people make the place’. That is, it is an individual's socioeconomic background — not where they live — that primarily determines their behaviours. Contextual effects suggest that the experience of residing in a certain place can also influence people’s orientations. Therefore, socio-economically similar people may think differently depending on their daily life context.

Many studies have highlighted the role of compositional factors — especially age, education, income, and occupation — in shaping the rise of populist and radical-right actors. But there is also evidence that local contextual factors matter. Populism geography cannot be explained entirely by voter composition. Therefore, a budding strand of research has stressed the relevance of contextual factors such as house price deflation, lack of public services and transportation, and the degradation of socio-cultural hubs.

Recent research suggests factors such as house price deflation, lack of public services and the loss of community centres and pubs play a role in the geography of populism

Finally, scholars have started uncovering more sophisticated mechanisms. Among these, ‘place resentment’ — the perception that one’s area and its dwellers are ignored, misunderstood, or disrespected — seems decisive in explaining geographic variations in populist radical-right attitudes. Studies on Germany and the Netherlands show clear evidence of this.

Except for a Dutch agrarian populist party — the Farmer-Citizen Movement — contemporary European populism does not normally target specific urban or rural voters; its socio-territorial bases are variegated. And while populists are overall stronger in remote places ‘left behind’, they have also reaped successes in highly urbanised contexts. Therefore, we should avoid giving both no and too much importance to geography in explaining populism. Territorial polarisation characterises radical-right phenomena more than purely populist ones.

No.60 in a Loop thread on the Future of Populism. Look out for the 🔮 to read more