Women are not a demographic minority, but they are certainly a minority in politics. Laura Sudulich, Siim Trumm, and Iakovos Makropoulos show that a significant gender resource gap remains a feature of contemporary parliamentary campaigns. Women face an uphill battle to get elected

Gender balance in political life is desirable for many reasons. Yet women remain a minority in almost all national parliaments. In the European Union, for example, the proportion of women in national parliaments is, according to the latest data, 33.5%. The picture is mirrored in other parts of the world.

When running for office, women face disproportionally large costs. They face greater harassment, and this forces them to modify their campaign activities in ways that can diminish their chances of gaining office. These women also tend to be newcomers to politics, who do not have well-established patronage networks. This puts them at a considerable disadvantage when it comes to fundraising.

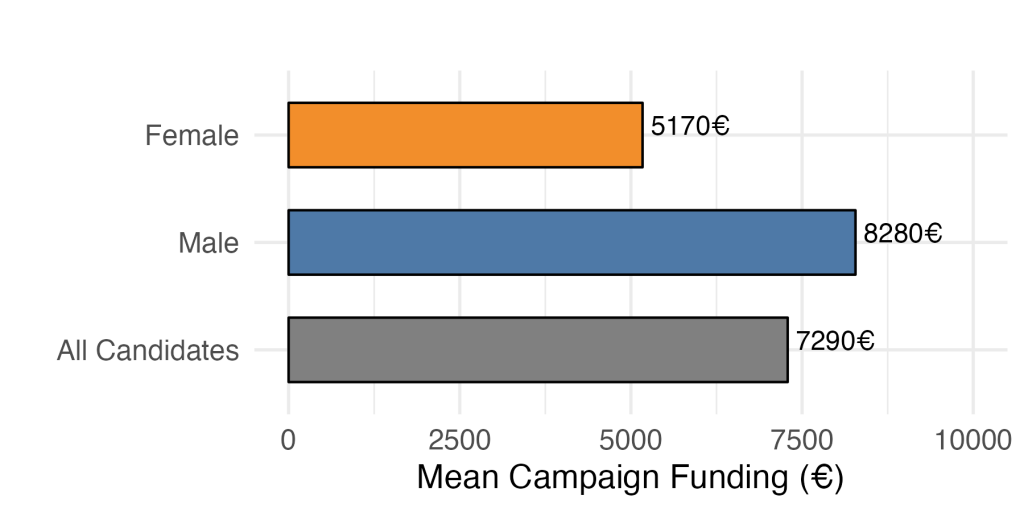

Our recent article in EJPR uses data from the Comparative Candidates Study, encompassing twenty-eight elections in sixteen countries between 2006 and 2017, to evaluate the size of the gender resource gap. The mean campaign spending across all candidates in our analysis is €7,290. What is perhaps even more interesting, however, is the difference between female and male candidates.

Survey data revealed that the average campaign budget for female political candidates is over €3,000 lower than for male candidates

We find the average campaign budget for female candidates is €3,110 lower than for male candidates: €5,170 versus €8,280. This is a notable difference, and gives male candidates a significant advantage. It allows them to pay for more leaflets, online advertisements, staff and the like. Greater campaign spending does not guarantee electoral success, but it certainly makes it that little bit more likely.

We also looked at the role of electoral institutions, partisanship, and candidates’ own political profile in mitigating – or aggravating – the gender resource gap. The two factors standing out here are incumbency and voluntary party quotas.

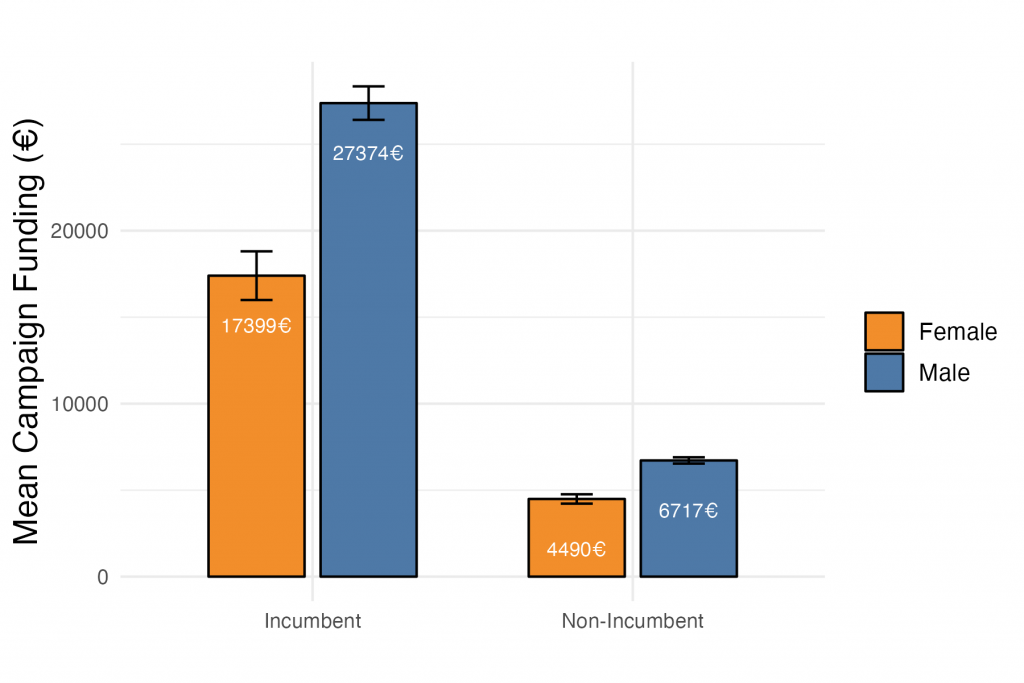

Incumbency aggravates the gender resource gap significantly. Women are clearly at a disadvantage among both challengers and incumbents. The financial gap, however, is particularly wide among the latter. Our multivariate models predict male challengers will spend €2,227 more than female challengers (€6,717 versus €4,490). The resource gap increases to as much as €9,975 when we compare male and female incumbents’ predicted campaign spend (€27,374 versus €17,399).

The benefits of incumbency apply to male and female candidates alike, but they translate into a disproportionately larger financial advantage for male candidates

Incumbency can bring major electoral benefits for candidates. It is associated with greater name recognition, proven track record, and ability to raise funds. These benefits apply to male and female candidates alike, but they translate into a disproportionately larger financial advantage for male candidates.

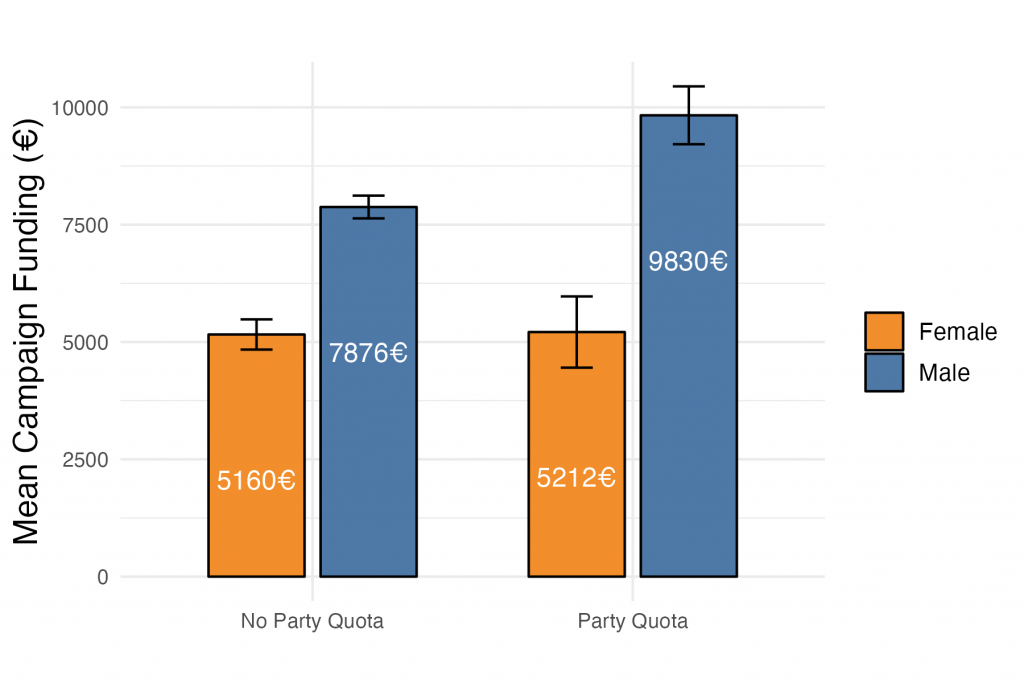

Voluntary party quotas also seem to widen the gap between and male and female candidates’ budgets. When we looked at candidates running for parties that do not use voluntary gender quotas, our multivariate models predicted the gender resource gap to be €2,716. Predicted campaign spending was €7,876 for male candidates and €5,160 for female candidates. The gap, however, goes up to €4,618 when a quota is in place.

Quotas increase the number of women running for office, but many female candidates still lack the campaign finances available to male candidates. This creates a larger resource gap in parties using quotas. Clearly, this widening of the gender resource gap is an unintended consequence of party quotas. Parties adopting, or willing to adopt, such a mechanism need to look more closely at this.

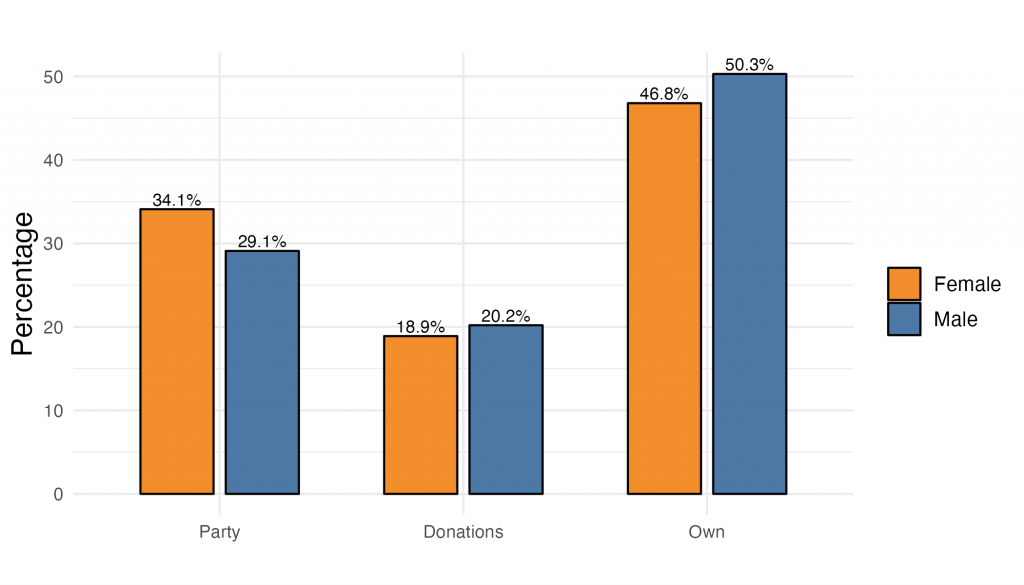

Candidates tend to rely most heavily on personal funds, followed by party contributions, and then donations. This holds for male and female candidates. The relative importance of these funding sources, however, is somewhat gendered.

Female candidates tend to receive a larger share of their campaign budgets from party contributions than their male counterparts: 34.1% compared to 29.1%. Personal funds make up, on average, a smaller proportion of female candidates’ campaign budgets than they do for male candidates: 46.8% compared to 50.3%. The extent to which donations make up candidates’ campaign budgets, however, is very similar for male and female candidates: 20.2% versus 18.9%.

The gender resource gap exists across electoral systems and irrespective of party ideology. Given that campaign spending can influence the likelihood of electoral success, the persistence of a gender resource gap in electoral campaigns is likely to keep hindering efforts to close the gender representation gap.

It is clear that parties can play an important role in supporting female candidates. Party contributions already tend to constitute a bigger part of female candidates’ campaign budgets than they do for men. This is of course a positive, but we must bear in mind that female candidates’ budgets are, on average, smaller than those of their male counterparts. Equitable party contributions are, sadly, not enough to level the playing field and create gender parity in campaign resources. These interventions will need to be even larger to make up for differences in fundraising capacity and access to personal funds.

Gender quotas alone are not enough to close the representation gap: more work is needed to create an equal campaign field

Campaign finance reforms might also help reduce the gender resource gap. One such reform could be the tightening of existing campaign spending limits. Our evidence suggests that the gender resource gap is pronounced in higher-cost environments, such as among incumbents versus challengers. Lowering the overall cost of election campaigns for individual candidates is likely to help reduce the financial disparity between male and female candidates.

Gender quotas alone are not enough to close the representation gap. They may increase the number of women candidates, but more work is needed to create an equal campaign playing field.

Addressing the gender resource gap requires structural changes, greater party support, and additional policies designed to provide women candidates with equitable financial backing. Political equity requires more than encouragement – it demands a firmer financial foundation that enables all candidates to run fair campaigns.