During the Covid-19 pandemic, many citizens put faith in the political system to keep them safe. Others were less trustful. Louise Halberg Nielsen argues that such trust, or the lack of it, was a key explanation for pandemic-era political disagreement. Her research findings could help societies navigate future collective crises more effectively

During the Covid-19 pandemic, public attitudes towards political restrictions, lockdowns, and support for voluntary behaviour changes quickly became marked by political disagreement. Government responses to the pandemic relied heavily on citizens’ willingness to comply with restrictions and policies. Understanding the drivers of citizens’ support for political responses to the pandemic was crucial, because it enabled societies to navigate the crisis more efficiently. Such understanding is key to tackling any societal emergency, whether a pandemic, an economic crisis, or the effects of climate change.

A common explanation for individual differences in pandemic-era attitudes and behaviours is the left-right ideological divide. Studies have found that left-leaning people were more concerned about the pandemic, more supportive of government restrictions, and more likely to report having changed their behaviours to slow the spread of infection.

Another factor is one's orientation towards the established political system. A person’s placement on the left-right political spectrum reflects a value-based conflict within the established political system. The divide between those with and without system trust, on the other hand, is a conflict between those who feel like they are inside and those who feel like they are outside 'the system' and the legitimacy of its solutions.

People who view the system’s decisions as legitimate, follow them. Those who do not trust the system are less likely to accept and follow containment recommendations

My research with Michael Bang Petersen in the European Journal of Political Research reveals that whether a person trusts the established political system explains their attitudes and behaviours related to the pandemic quite separately from their ideology. Those who support the system view the system’s decisions as legitimate and, consequently, follow them. Those who do not trust the established system will not view its decisions as legitimate. These people were thus less likely to accept and follow containment recommendations.

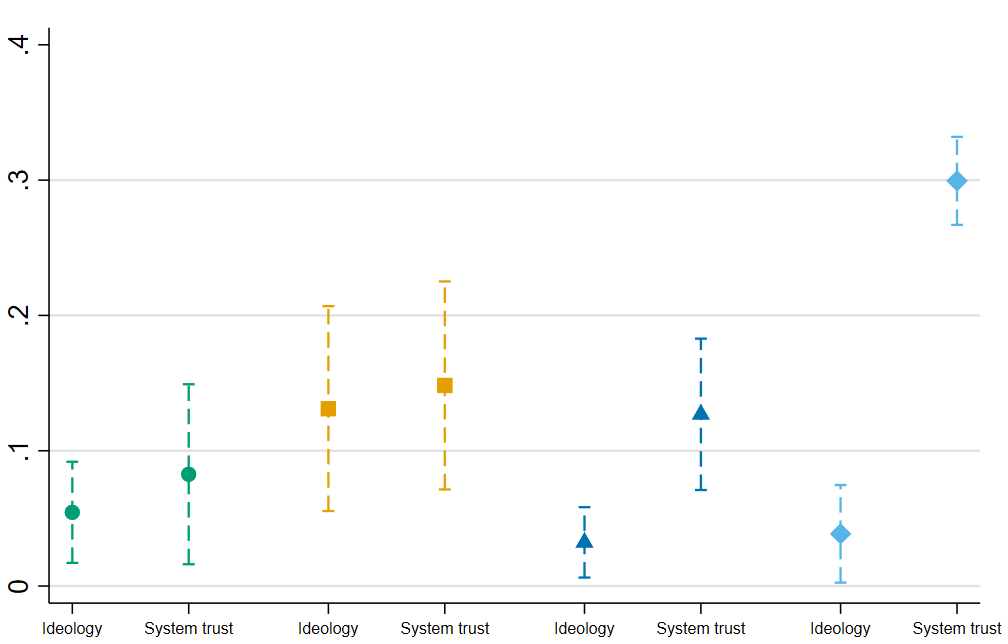

Our research finds large differences in attitudes and self-reported behaviours between those who trust the system and those who do not. Those who trust the system perceived a bigger threat from Covid-19, and were more supportive of their government's Covid-19 containment measures. They were more likely to report having changed their behaviour to slow the spread of the virus, and also report much greater intention to get themselves vaccinated.

As other studies have shown, differences between left- and right-oriented people were also considerable. Left-oriented individuals perceived a bigger threat, and were more supportive of government containment policies. They were more likely than right-oriented people to report having changed their behaviours, and they report being more willing to receive a vaccine.

Behavioural differences between people who trust and do not trust 'the system' were even bigger than those between left- and right-leaning people

Yet, the differences between those who trust and those who do not trust 'the system' were even bigger, especially in terms of self-reported behaviour changes. This highlights the crucial role of trust in a society. Governments rely heavily on citizens to change behaviour voluntarily during crises, and it appears that compliance with recommendations is much higher among those with trust in 'the system':

The pandemic required a massive collective effort to slow the spread of the virus. Government responses such as lockdowns relied heavily on citizens’ support and willingness to comply.

The pandemic will not be the last crisis that requires collective action

The pandemic will not be the last crisis that requires collective action. The climate crisis, for example, requires immediate collective action, too. So, what can we learn from Covid-19 about handling societal crises?

Our findings suggest that to increase public support for collective crisis response, policy-makers must appeal to the entire ideological spectrum. However, they must also try to appeal to those who do not trust 'the system'. Moreover, our findings highlight the importance of building and upholding citizens’ trust in the political system outside times of crisis. System trust is a critical resource in effective crisis response, and it may prove difficult to build once a crisis has already erupted.

What an insightful analysis of how trust shapes crisis responses! The connection between system trust and Covid-19 behaviors offers valuable lessons for managing future emergencies. This research highlighting the role of citizen-government relationships could really help improve crisis communication and policy implementation for challenges ahead.