If you’re waiting for the 'big one', it’s probably already come and gone. Tom Johansmeyer brings a new dataset and a fresh perspective to the threat of cyber catastrophe and ensuing economic carnage. With only $300 billion in impact over 25 years, he says, cyber catastrophes are more bark than bite

The spectre of the 2017 NotPetya cyber attack looms large. Launched by GRU, an intelligence organisation in the Russian military, it affected major companies around the world, spreading quickly from its intended target in Ukraine.

NotPetya’s been described as an act of cyber war, 'devastating', and the 'costliest cyber attack in history'. It’s none of those. The fact that it was recent and much bigger than any other cyber attack over the past decade makes NotPetya look much worse than it really was. There was no stock market response, and the headline victims moved on relatively quickly. And it certainly wasn’t an act of cyber war. NotPetya lacks the violence of impact required by the godfather of war himself, Carl von Clausewitz. But was it the costliest cyber attack? That’s a bit tougher to nail down.

Russia's NotPetya cyber attack was recent and much bigger than any other over the past decade. But was it the costliest?

To say that NotPetya had the greatest economic impact of all cyber catastrophes, you’d need to know which other cyber attacks have occurred and how much they cost. Without a central database, that’s virtually impossible. To address this, I’ve pulled together the first database of economic loss estimates from cyber catastrophe events.

The results are eye-popping.

Developing a database of historical cyber catastrophes starts with defining parameters. I set a cutoff of $800 million per event, adjusted for inflation to 2023. I've excluded single-company attacks, because the narrowness of the focus is not catastrophic. This leans on the subjective measure of breadth used by PCS, which calculates industry-wide insured losses from natural and man-made catastrophe events for the insurance industry. (Disclosure: I led PCS for seven years, until May 2023.) For example, the $1.4 billion economic loss for Equifax meets the cost threshold but not the breadth test.

The $800 million threshold may seem odd, particularly given how close it is to a round number like $1 billion. The method to the madness is that lowering the threshold from $1 billion brings in two more events. Only 21 events since 1998 qualify, so increasing the historical record is worth the awkward threshold.

To arrive at 21 events since 1998, I pulled data on historical economic losses from cyber catastrophes from publicly available sources, which is the primary limitation of the study. Unfortunately, many estimates come from popular media sites and corporate blogs. Iterative internet searches for new events and additional estimates revealed events and input data to be used in determining the estimated economic loss for each event.

Methodological information for the publicly available estimates is virtually non-existent, and some sites presumably reference (but don’t link to) long-gone sources. Essentially, I'm relying on judgment and comparison of original estimates without a benchmark to make the best of a bad situation. That said, many of the estimates appear to have been recycled and republished, which offers at least a veneer of respectability. Future researchers should use the full dataset and underlying estimates, which should be published later this year, to advance scholarship in this area.

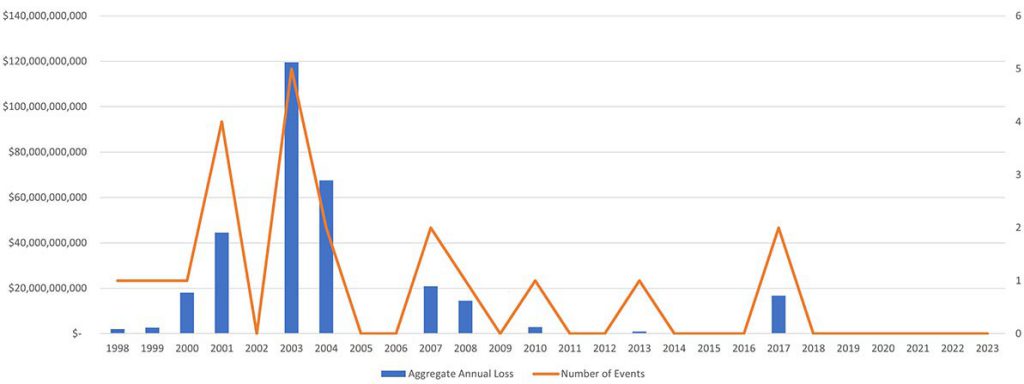

The 21 events identified above occurred in 11 of the past 25 years. Approximately 93% of economic loss occurred from 1998–2008. The busiest years were 2003 and 2004, which together accounted for $187.1 billion of the 25-year period’s $310.4 billion in aggregate economic loss. The two largest economic losses from cyber catastrophes – SoBig and MyDoom – came in 2003 and 2004, respectively. The former generated an economic impact of $65.2 billion; the latter $66.6 billion. The average annual loss fell just a hair short of $12 billion, with the average event loss at $14.8 billion.

Over the past 25 years, approximately 93% of economic loss from cyber attacks was incurred before 2008

Eight events exceed the event average, and NotPetya is not one of them. In fact, the last above-average event was StormWorm in 2007, which generated economic losses that climbed to $16 billion.

So, what of NotPetya?

The official US government estimate of $10 billion in 2017 adjusts to $11.9 billion in 2023 dollars. That does put it well below the event average. NotPetya becomes more interesting, however, when we look at it alongside WannaCry, which came just before it. Estimated by risk modelling firm Cyence to have caused $4 billion in economic losses ($4.8 billion in 2023 dollars), WannaCry was a small event on its own. Taken together, WannaCry and NotPetya bring 2017 more than 30% above the annual average for the 25-year period I studied. In fact, 2017 is the only above-average year for aggregate economic losses from cyber catastrophes since 2008.

The 2017 data does more than lower the bar for the severity of recent cyber catastrophe events, particularly in comparison with brutal years such as 2003 and 2004. It also offers a benchmark for determining realistic disaster scenarios. In that year, two states conducted back-to-back cyber attacks that had widespread catastrophic impact. It sounds like a Hollywood storyline waiting to happen. Yet, the outcome of a scenario that probably sends shivers up your spine was an aggregate $16.7 billion. That’s roughly 20% of the economic impact of Hurricane Ida.

In 2017, two states conducted back-to-back cyber attacks that had widespread catastrophic impact. Yet these attacks caused only 20% of the economic impact of Hurricane Ida in 2021

Alarmist projections on the potential carnage from catastrophic cyber attacks doesn’t imply extreme caution for the common good. Rather, it suggests a misunderstanding of the risk and suboptimal allocation of security resources. It’s better to get it right than it is to be unnecessarily cautious. Cyber security is doubtless important, and the fact that there hasn’t been an above-average economic loss from a cyber attack since 2007 is instructive. The cyber domain has changed, and our attitudes toward the potential cost of catastrophic cyber attacks should, too.