Will Edmonds argues that the UK’s means-tested approach to social housing is permitted by a culture that criminalises poverty, and has enabled tragedies like the Grenfell Tower fire. A look through the history of UK social housing shows that the government should adopt a humane, universalist approach

In the UK, social housing (accommodation rented at below-market price and allocated on the basis of need) is often seen as a last resort for the ‘undeserving poor’. The negative stereotypes attached to such housing are a direct result of its segregated, means-tested provision. A media and political narrative that criminalises those on low incomes strengthens this perception. Negative stereotypes, alongside a culture of cost-cutting, precipitates the organised abandonment of low-income people, and permits tragedies like the fire at Grenfell Tower, which killed 72 people in 2017.

We can look to British history for solutions. Inter-war social housing provided tenants with respectable accommodation, and post-war social housing took a broader, universalist approach. A humane approach to addressing the housing crisis is possible – desirable, even. Governments should set high standards for the private provision of housing, and take a direct role in developing it. Culturally, housing should once again be a right, rather than a commodity to trade and accumulate.

A century ago, my great-grandparents Henry James and Lillian Maud Edmonds were living in Bermondsey, then a squalid waterfront district of London where regular flooding, slum housing and crumbling infrastructure meant disease ran rife. The couple then moved south-east, to the newly built Downham Estate in Lewisham.

My grandad, Ronald Edmonds, was born and raised on the estate, and remained there until he died, aged 92, in 2023. The Downham Estate largely comprises two-storey terraced houses with gardens, of the type pictured below, nestled among tree-lined cul-de-sacs with open green spaces.

In contrast with the squalor of 1920s Bermondsey, the likes of the Downham Estate were a 'paradise' that transformed families' lives with luxuries such as running water, indoor toilets and private gardens.

Inter-war housing estates transformed working-class families' lives with luxuries like running water, indoor toilets and private gardens

However, the estate was selective: tenants had to demonstrate 'good character' and steady income. Local councils offered homes only to the respectable working class; the unfortunate were left to the slums.

After the second world war, Clement Attlee’s Labour government passed the Housing Act 1945, prioritising public housing as a social right for all. It thus abandoned the moralistic prioritisation of accommodation that characterised inter-war housing policy, in favour of a universalist approach. In the words of Aneurin Bevan, then Minister of Health:

We shall persist in the building of new permanent houses until every family in the country has a good, separate, modern home.

Aneurin Bevan, 1949

The Golden Lane Estate in the City of London captured this spirit: it is architecturally interesting, with a striking and memorable façade that hides a concrete labyrinth of courtyards, gardens and walkways. It is a small, self-contained neighbourhood in the heart of the City.

Perched atop one house, a rooftop garden provides city views of St Paul’s Cathedral to its South, and the Olympic Stadium to its East. Nowadays, the garden remains closed because risk assessors are concerned about rot on the wooden pergola. You can glimpse the garden's impressive concrete canopy only from afar:

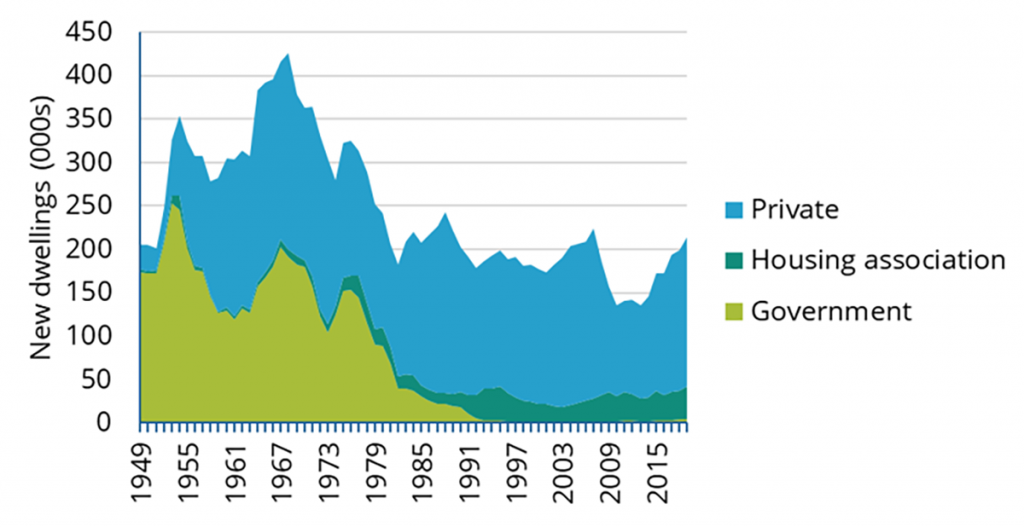

The graph below shows the source of new dwellings in England since 1949. The universalist approach was led by government, which provided two-thirds of all new housing in the 1950s. By 1969, 31% of Britons lived in social housing.

In the 1980s, then UK prime minister Margaret Thatcher began dismantling the postwar consensus characterised by an interventionist government. Housing associations (government-contracted private companies providing social housing) gained importance at the expense of direct government provision. Thatcher argued that competition would improve the quality and reduce the cost of housing, with oversight provided by a regulator, the Housing Corporation. All social housing was to be provided through housing associations; the government-built social house was dead.

Thatcher’s Right to Buy scheme, which still exists, has so far seen 1.7 million social homes sold off into private ownership. Following the scheme's introduction, UK citizens no longer regarded housing as a right, but as a commodity to earn, own – and trade. The aspirational poor could own their properties; social housing was what remained for those left behind.

The Thatcher government's Right to Buy scheme transformed British people's perception of housing from being simply a place to live into a tradeable commodity

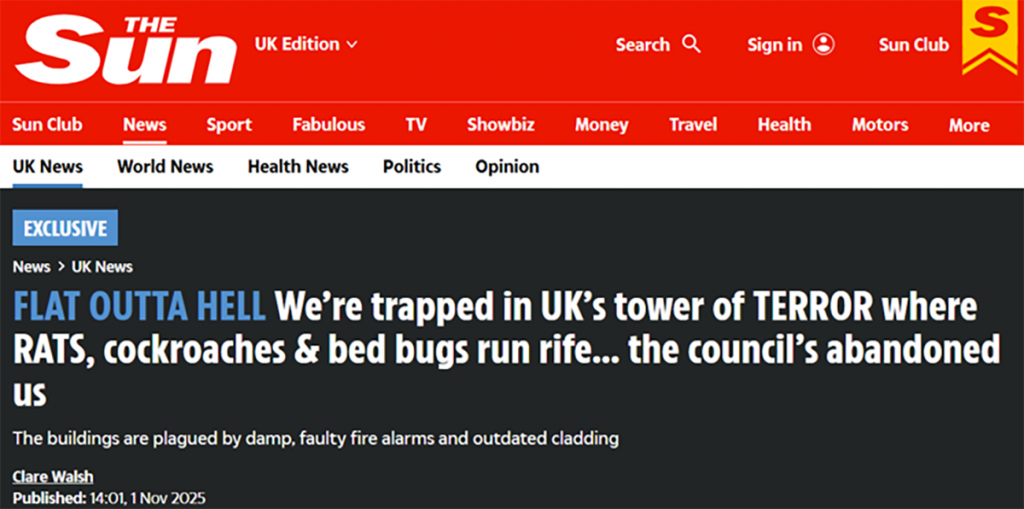

Social housing therefore became 'poor housing for poor people'. As this study from Durham University demonstrates, those in social housing are seen, and see themselves, as second-class citizens. The government, media and society reinforces the perception that social housing as dangerous, dirty and drug-ridden, and its tenants lazy, undeserving and criminal.

In the early hours of 14 June 2017, a fire broke out at Grenfell Tower, a 1970s high-rise owned by the London Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. The fire, which killed 72 people, was not merely a regulatory failure, but the result of the ‘organised abandonment’ of low-income people. Meanwhile, the landlords of Grenfell Tower, Kensington and Chelsea Tenant Management Organisation, paid its senior staff £800,000 in 2016–17, rising by 23% to £987,000 in 2017–18.

The landlords had installed the building’s cheaper, flammable cladding to comply with cost-cutting measures. The safety of its tenants was an acceptable corner to cut. Tenants had raised fire safety concerns, but they were ignored or – worse – pursued legally with claims of defamation. Their voices were silenced in life, and extinguished in death. Now, the mummified remains of the block still stand, minutes away from the affluent neighbourhoods of Notting Hill and Kensington.

The UK housing crisis is not just market failure – it is a social failure that casts people on in receipt of welfare, as undeserving, lazy and criminal. This unrelenting narrative permits the abandonment of those living in poverty. In the tragedy at Grenfell, it directly cost lives.

My grandad was none of these things. He worked hard to save and provide for his wife, children and myself.

History teaches us that a universal housing approach can provide homes that anyone would be grateful for. A humane housing policy would treat homes as a right, not a commodity. It would empower local authorities to build mixed-income, high-standard estates, and enforce minimum standards in the private housing market.

A decent home should never be a privilege. It should be a public promise.

"After the second world war, Clement Attlee’s Labour government passed the Housing Act 1945, prioritising public housing as a social right for all. It thus abandoned the moralistic prioritisation of accommodation that characterised inter-war housing policy, in favour of a universalist approach."

Complete nonsense, no such Act.

Section 1 Housing Act 1949 removed the 'references to the working classes from certain provisions of the Housing Act, 1936.' Pure gesture politics that made no diffeence to any local authority's housing policy. No local authority had restricted the provision of housing to the 'working classes', and no authority changed its policies as a result of that part of the 1949 legislation.