Fabio Bordignon explores the relationship between pseudoscientific beliefs and support for populist parties. This link, he argues, changes according to the political trajectories of populist actors and their paths toward institutions

The spread of science-related populism expands and reframes both classic opposites of populist ideology: the pure people and the corrupt elites.

While exalting the natural, uncontaminated wisdom of the people, populist narratives promote the pseudo-expertise of alternative scientific authorities. In parallel, science and scientists find growing prominence among the corrupt elites targeted by populist actors. During the Covid-19 pandemic in particular, and given the increasing salience of issues such as (anthropogenic) climate change, science has become a political battleground.

In light of the recent pandemic, and the increasing salience of climate change, science has become a political battleground

This Loop series launched by Mattia Zulianello and Petra Guasti aims to reinterpret the complex and changing nature of populism. I argue that such a reinterpretation necessarily involves considering the role of science.

Is there an empirical link between the popular spread of pseudoscientific beliefs and the electoral performance of populist parties?

Research findings support this idea. My recent article in the Journal of Contemporary European Studies draws on existing literature on science-related populism. In it, I investigate the relationship between pseudoscientific beliefs, the spread of epistemological populism, and electoral preferences, using survey data collected by Demos&Pi and Unipolis in France, Germany, Italy, The Netherlands, and the United Kingdom (May 2021). I constructed a Pseudoscientific Beliefs Index (PBI) to study the social and political determinants of such beliefs.

Results show that exposure to scientific information does not ‘protect’ against unsound scientific claims, unless it is complemented by a correct understanding of the division of labour between expert scientists and laypersons. As one might expect, there is a strong association between pseudoscientific views and distrust of official science. But pseudoscientific views also correlate with reliance on alternative sources and alternative scientific authorities. Survey subjects took their advice from non-mainstream sources of scientific information. These sources were a mixture of ordinary people, and ‘authorities’ (and celebrities) from other domains.

My study suggests an association between the embrace of ‘alternative’ scientific views, science-related conspiracy theories, and the rejection of traditional categories of left and right

The study also suggests an association between the embrace of ‘alternative’ scientific views, science-related conspiracy theories, and the rejection of traditional categories of left and right. But the main political pattern detected consistently across Western Europe links the adoption of pseudoscientific views to support for populist parties. The relationship with party proximity is positive and statistically significant for 10 of the 11 parties PopuList classifies as populist.

Among the national cases in this study, the Italian one was particularly interesting for at least two reasons.

Italy was one of the European countries most affected by the first wave of the pandemic.

The 2018 general election saw double populist success for the radical-right Lega and the post-ideological or valence populist Movimento 5 Stelle (M5S). This particular election therefore configured a relevant ‘populist experiment’.

In 2021, four of the five major Italian parties were classified as populist: M5S, Lega, and the two centre-right parties, Silvio Berlusconi’s Forza Italia (FI) and Giorgia Meloni’s Fratelli d'Italia (FdI). For all four, party proximity emerged as significantly associated with pseudoscientific beliefs. My survey results detected no relationship for the centre-left Partito Democratico (PD).

The multi-country survey took place while Mario Draghi’s newly established technocratic government (2021–2022) led the country. His tenure followed the fall of the yellow-green (M5S-Lega: 2018–2019) and yellow-red (M5S-PD: 2019–2021) governments. Draghi, a former President of the European Central Bank, enjoyed the support of an extra-large majority excluding only FdI and other minor parties.

The Draghi administration's most important Covid-related measure was the so-called Green Pass. This was a vaccine passport imposing restrictions on travel and access to (indoor) public spaces. In the months following its introduction, even parties belonging to the government majority expressed doubts, or open criticism, of these measures. In general, M5S and Lega increasingly felt the call of the (populist) wild, amplified by the approaching end of the legislature and the booming rise of FdI.

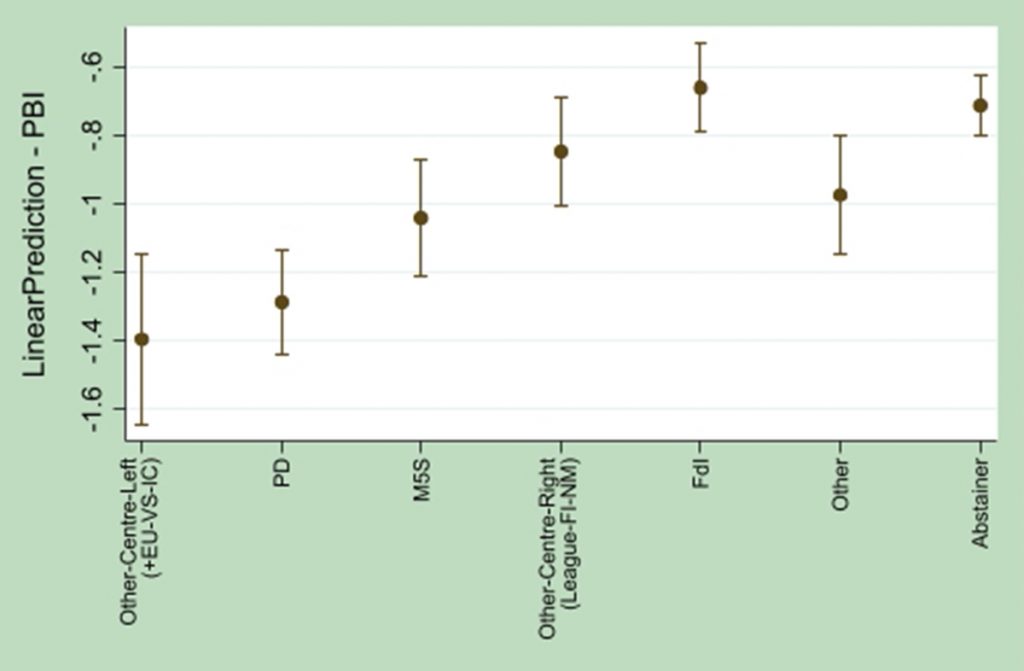

Examining the electoral pattern of pseudoscientific beliefs at the end of the legislature thus offers important insights into populist parties' evolution. A LaPolis-University of Urbino Carlo Bo survey immediately after the September 2022 election allows us to update the relationships between the PBI index and voting choice. It recorded significantly higher values for FdI and the other parties of the (winning) centre-right coalition.

M5S still displayed higher values than the PD and other centre-left parties. Its estimated value, however, was approximately the PBI average. This trend is particularly notable when examined in light of M5S's overall trajectory toward institutionalisation. Its current leader, Giuseppe Conte, led the government through the harshest phases of the pandemic, which required the implementation of a national lockdown. Preliminary results in the graph suggest a partial loss of M5S's populist traits and populist appeal. Voters sharing pseudoscientific views appear to have aligned themselves predominantly with centre-right parties, or chosen to abstain from voting.

The unprecedented abstention rate in the 2022 Italian elections suggests that science-related populism may find different electoral outlets in different political phases

The 2022 elections saw the unprecedented growth of abstention, which reached an all-time high of 36%. We can read this as an effect of the partial exhaustion of the populist political supply after 2018. It seems to suggest that science-related populism – and perhaps the demand side of populism in general, in Italy and elsewhere – may find different electoral outlets in different political phases. Alternatively, it may even remain dormant (and then explode again).

Of course, these preliminary findings are not enough to assert a direct effect of pseudoscientific beliefs on the 2022 vote. However, they emphasise that populism is a moving target. It comes in different degrees and kinds, continually finding new social triggers and electoral avenues.

59 in a Loop thread on the Future of Populism. Look out for the 🔮 to read more