In May, Venezuela’s President Nicolás Maduro visited Moscow to sign a 'strategic association' agreement with Russia. John Chin and Justin Lee argue this is one manifestation of a larger trend of rising sharp power in Latin America, which has major implications for US strategy and autocratisation in the region

The United States needs a strategy to address two interrelated geopolitical challenges in Latin America: reversing democratic stagnation and erosion and countering the rising influence of extra-regional non-democratic major powers led by China and Russia.

Two-thirds of Latin Americans still live in liberal or electoral democracies. Yet the latest V-Dem democracy report notes that democracy across Latin America has weakened in recent years. Venezuela, Nicaragua, and El Salvador have seen the largest declines in electoral democracy scores. Since 2019, Nayib Bukele has become the region’s newest and most popular autocrat. Since 2023, Mexico has entered the 'democratic grey zone' at the gates of authoritarianism.

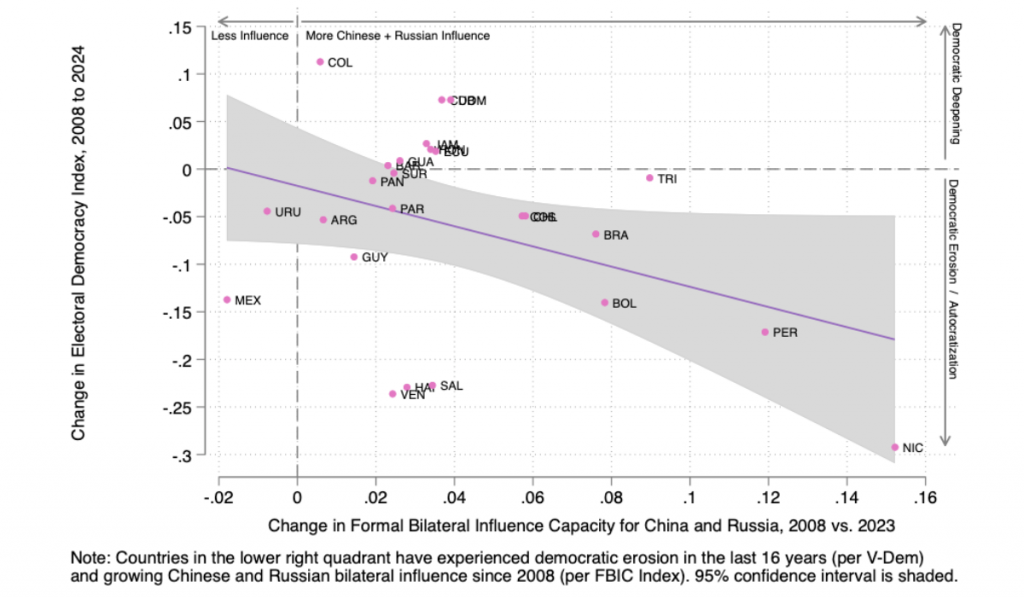

Most countries in the region underwent democratisation between the 1980s and early 2000s during the height of the so-called third wave of democracy. Now, however, the region has been swept up in the third wave of autocratisation. The number of countries in the western hemisphere undergoing autocratisation has exceeded those democratising each year since 2008, per data on episodes of regime transformation. By 2024, seven countries in the region were autocratising. The most recent to join this list are Peru, since 2020, and Argentina under Javier Milei since 2023.

Popular support for democracy declined in Latin America a decade ago and hasn’t recovered. Political polarisation has since created opportunities for populist leaders to grab executive power

The region’s democratic crisis is multifaceted, driven partly by endemic local corruption and organised crime. Bolivia’s democracy briefly collapsed due to a 2019 'coupvolution'. But, unlike during the Cold War era, praetorian militaries are not driving the current regional wave of democratic backsliding. Instead, democracy faces pressures from above and below (and without). Popular support for democracy declined in the region a decade ago and hasn’t recovered, according to AmericasBarometer surveys. Rising dissatisfaction with democracy and political polarisation have created opportunities for populist leaders to grab executive power.

The US has longstanding hegemonic influence in the western hemisphere, born of proximity, economic importance (from aid to trade), and the Monroe Doctrine legacy (including a sordid history of military and covert interventions). Today, the US retains more formal bilateral influence capacity (FBIC) in Latin America than any other country. In recent years, however, its lead has shrunk, while China's has skyrocketed to become the second most influential country in the region, per FBIC.

China’s approach to wielding influence relies on leveraging goodwill born of economic engagement, such as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). China is South America’s largest trading partner; Brazil trades twice as much with China as the US. Yet critics accuse China of pursuing 'debt-trap diplomacy'. Indeed, this spring, Panama became the first Latin American country to quit the BRI. Yet China’s activities have increasing strategic implications. US military leaders worry that China’s newfound access to 'dual-use' facilities and ports near chokepoints could be a stepping stone to naval bases.

Russia’s influence pales in comparison to China – mainly because it has less market power, though Russian military and diplomatic support has propped up anti-American dictatorships in Cuba, Nicaragua, and Venezuela. Russian military contractors deployed to Venezuela in 2019 to protect Nicolás Maduro amid rising fears of a US-sponsored coup. The Kremlin likewise supplied arms to suppress pro-democracy opposition to Nicaragua’s Daniel Ortega.

Since 2008, rising Chinese and Russian 'sharp power' has fuelled democratic backsliding and authoritarian consolidation

Russia and China also have extensive Latin American propaganda operations. These amplify narratives favourable to anti-American, autocratic governance. In 2019, Russian-owned nuclear corporation Rosatom hired spin doctors to support Evo Morales' re-election in Bolivia. That year, nearly 10% of tweets supporting mass protests in Chile originated in Russia. Both countries also export surveillance technology to repressive Latin American regimes. Since 2008, rising Chinese and Russian ‘sharp power' has fuelled democratic backsliding and authoritarian consolidation.

After decades of 'benign neglect', Latin America is a US foreign policy priority early in the second Trump administration. Yet the Trump administration’s early hemispheric policy, like Biden’s before, lacks a coherent strategy for defending democracy amid great power competition. The main impetuses for the region's rising importance are reducing illegal immigration and flows of illicit drugs. But it is short-sighted to overlook rising authoritarian influence in Latin America in favour of a purely transactional policy.

The Trump administration’s early hemispheric policy lacks a coherent strategy for defending democracy amid great power competition

Democratic renewal – including combating corruption and organised crime – is critical to the long-term success of efforts on immigration and drugs. Reducing extra-regional autocratic influence and bolstering democratic partnerships in the region is therefore a US national interest and reflection of American values.

A new hemispheric strategy could borrow from the Cold War Kennedy administration playbook after the Cuban revolution. Such a strategy would seek to negotiate a new 'alliance for progress' that would benefit the US and its democratic American partners. It would also seek to counter growing Chinese economic influence not by raising tariffs, cutting foreign aid, and ignoring human rights abuses in the region but by promoting intra-regional trade and supply chain networks – and committing to greater US aid and investment and cooperative multilateralism – to promote trust in American leadership. The Trump administration’s proposal to increase Development Finance Corporation funding to 'make the Americas grow again' is a welcome step.

For better or worse, democracy’s fate in the Americas is tied to great power competition. Whether or not the Americas can be made 'safe for democracy' remains to be seen. To give democracy a chance, the US must commit to resist sharp power in the Americas.