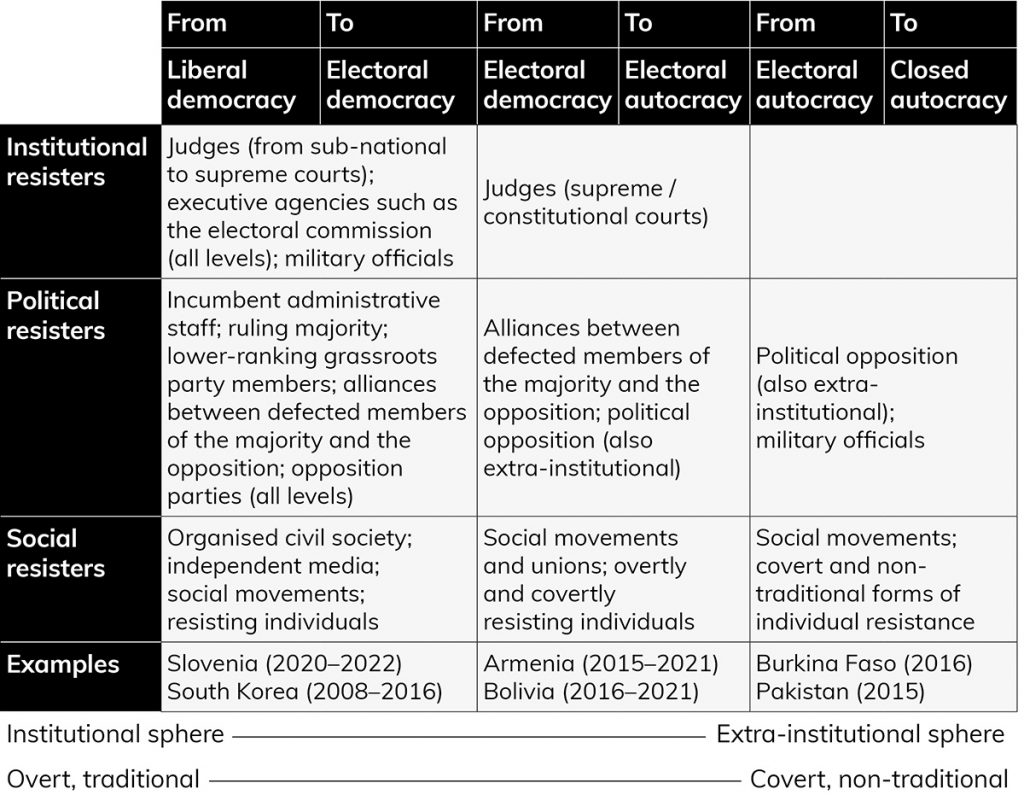

Resistance to autocratisation is not limited to democracies. In fact, Luca Tomini, Suzan Gibril, and Venelin Bochev demonstrate that the main actors resisting autocratisation and their strategies vary across regime types. Analysing resistance strategies from democracy to fully authoritarian regimes can be invaluable beyond academia to practitioners and activists

Scholars have analysed extensively the structural (pre)conditions, modalities, motivations and strategies that empower autocratising actors. Recent literature, however, has begun to focus on other side of the equation: the opposing actors that anticipate and challenge autocratisation.

We are calling for a 'resistance playbook'. Creating such a playbook would provide an understanding of resistance against autocratisation in whatever context it occurs, with updated and exploitable scientific knowledge.

We acknowledge the importance of prevention via strategies of civic engagement. We acknowledge, too, the role of opposition actors and others based on accountability mechanisms. Yet we argue that scholars must also explore in detail strategies that seek to counter autocratisation once the process has begun.

Creation of a 'resistance playbook' would help scholars understand resistance against autocratisation wherever it occurs

Moreover, we suggest that resistance to autocratisation should go beyond institution-based strategies applicable only to Western liberal democracies. Rather, it should analyse various actors in hybrid and autocratic regimes elsewhere in the world.

In our research, we compare strategies pursued by institutional, political, and social actors (hereafter resisters) in the United States, Israel, Ecuador, North Macedonia, Tunisia and South Sudan. This covers regime types ranging from liberal and electoral democracies to transitory and authoritarian regimes.

Resisters employ diverse strategies. These range from intra-incumbent division to mass mobilisations, formation of anti-autocratiser alliances, parliamentary boycotts, and civil disobedience. They also include military coups with reference to a variety of conventional and alternative tools and forms of resistance.

We show that liberal democracies allow state and local actors in public administration, the judiciary, the legislature, and even the incumbent coalition, to resist autocratising incumbents without restriction.

Accordingly, actors can rely on horizontal accountability. They can dissociate themselves from the autocratiser by splitting from the coalition, and set the tone for other forms of resistance. In electoral democracies and hybrid regimes, mechanisms of checks and balances are unreliable. Resistance, therefore, falls mainly upon the political opposition. Such opposition strategies range from the use of classic oversight tools to unconventional measures such as parliamentary boycotts.

By contrast, in authoritarian regimes, the ‘rules of the game’ are deliberately hazy, while institutions and opposition face significant challenges. Here, informal institutions or groupings that pass under the autocratiser's radar bolster popular mobilisation against the incumbent. And this enables resistance in a variety of forms.

We propose two hypotheses for future research. First, the more authoritarian the regime, the fewer the options for resistance. This, we argue, could also mean fewer chances for success. Consequently, we hypothesise that the more diffuse and transversal is actors' resistance, the greater their chances of success.

From liberal democracy to established autocratic regimes, successful cases of resistance appear to be those in which opposition actors can build synergies and create a 'network' of resistance. Thus, they overcome political and ideological differences and rely on coordination between political, social, institutional and even external actors.

Second, the more authoritarian the regime, the more resistance will slide from being within to being outside formal institutions. In liberal democracies, processes of autocratisation usually encounter effective obstacles in actors within the institutions themselves, and in the incumbent coalition. In electoral democracies, we find key actors of resistance in the political opposition. They act through the classic channels of parliamentary and electoral politics and, sometimes, through extra-institutional means such as parliamentary boycott, among others.

The more authoritarian the regime, the more resistance will slide from being within to being outside formal institutions

In established authoritarian regimes, on the other hand, key actors of resistance are primarily social. They act either through overt dissent and contentious politics or, if that is not sufficient, through non-traditional, covert, and even delocalised forms of resistance.

Hence, our second hypothesis suggests that resistance should be tailored to the context. It should be targeted primarily at its most effective dimension, such as strengthening institutions of horizontal accountability in liberal democracies – and empowering opposition actors in electoral democracies and electoral autocracies – in order for them to be able to contest elections.

Over the last decade, authoritarianism has been on the rise around the world. We have heard few success stories of autocratisation resisters. Yet our understanding of autocratisation remains incomplete if we focus solely on the autocratisers and neglect their opponents.

Effective strategies against autocratisation are invaluable. However, no recipe for resistance is failsafe. In the long term, our research aims to piece together a theory of autocratisation that focuses on 'drivers' and 'resisters'. In the short term, we need a collective theoretical and empirical effort to create a functional resistance playbook. Doing so requires us to overcome conceptual and methodological boundaries. It also needs collaboration between practitioners, civil society organisations, media and journalists, officials, and political actors.

Our understanding of autocratisation remains incomplete if we focus solely on the autocratisers and neglect their opponents

Autocratisation can start in different regime types with different characteristics. Therefore, the study of resistance to autocratisation cannot be limited to democratic regimes. It requires a wider scope, beyond a single type of political regime.

Resistance is a combination of activities by a network of often interconnected actors aiming at curtailing autocratisation in a regime. What distinguishes regime types is the range of resistance tools and strategies these actors can effectively deploy. Better regime classifications matter to this endeavour. The more precise our classifications, the better we can identify how to counter autocratisation in each context.

Resisting autocratisation is closely linked to preventing autocratisation. We must consider multiple actors in the analytical framework, as well as regional comparisons using specific regional expertise. Quantitative and qualitative findings should also feed off each other. If we accept this complexity, the obvious consequence is that we need a collective effort to coordinate between scholars with different distinct skills. In this way, each will discover a missing piece of the autocratisation puzzle.