Many young people are at the forefront of demanding positive change, such as in the struggle for racial justice. Temidayo Eseonu draws on her research with racially minoritised young people to show how Afrofuturism can help them understand racism and resist its impact on their lives. Tapping into young people’s democratic potential, she says, can give us all hope for the future

We are living through an era of polycrisis. Climate catastrophe looms. Wars and conflicts around the world are precipitating humanitarian crises. Social inequalities abound, and in the UK, where I am based, people face an acute cost-of-living crisis. What kind of a world, I wonder, are we handing down to the next generation? I am particularly interested in Hans Asenbaum’s proposition about the untapped democratic potential in who we are and who we choose to be. And I am especially interested in how this pertains to young people.

Racially minoritised young people bear the brunt of society's persistent racial inequalities. A 2022 report found that in northern England, these children and young people generally experienced more inequality than their white counterparts. The Covid-19 pandemic only exacerbated these inequalities. In the face of these realities of systemic and institutional racism, young people ought to have a say in how we tackle such disparities. But, of course, electoral participation and representative democracy is not an option if you're under 18 years old.

As a result, young people are increasingly turning to youth activism to effect change. Such activism typically occurs because in the digital age, youngsters can access more easily information on issues they care about. Youth educational programmes are therefore important sites of transformation to realise young people's democratic potential in pursuit of racial justice.

How do we get young people, especially those who are racially minoritised, to pay attention to racist structures that affect agency over their lives? How do we get them to imagine transformed societies, free from racial injustice, that would mean better lives for them? And how can we bring young people’s untapped democratic potential to the surface, channelling it into political action that transforms democracy? My research aims to answer these questions.

There are no simple answers, but the community of democracy researchers, practitioners and activists continue to grapple with these questions in their work.

Our community of democracy researchers can create spaces that invite young people to explore their democratic potential

This blog series asks what role the community of democracy researchers, practitioners and activists can play. Well, for a start, it can create spaces that invite young people to explore their democratic potential. In my research with young people, I curate spaces for young people to participate in anticipatory and liberatory world-making. I emphasise understanding histories of oppression, but I also encourage them to imagine alternate visions for a just world.

I use the concept of Afrofuturism in educational programmes with racially minoritised young people, mostly in the North of England. Afrofuturism draws our attention, using aesthetic mediums, to historical patterns of racial inequality and how they manifest in the present. Afrofuturism centres Black people’s subjectivities, inviting them to imagine new futures for themselves. And Afrofuturism as a method of critical qualitative inquiry supports young people's self-transformation. It encourages them to identify racial injustice and to resist racist hegemonic ideas and practices.

Afrofuturism supports young people's self-transformation. It encourages them to identify racial injustice and to resist racist hegemonic ideas and practices

My current project uses a strategy of resistance to deconstruct dominant narratives about Black people and culture, by telling ‘the story’ differently. Emilie Townes calls this 'countermemory'. To explore Black history, I took a group of young people to the International Slavery Museum in Liverpool. There, we examined the history of resistance by Black people in Manchester to centre Black art, literature and oral histories. Following our visit, I asked the young people to produce a piece of art about something they had learned. Here are some examples of their creations:

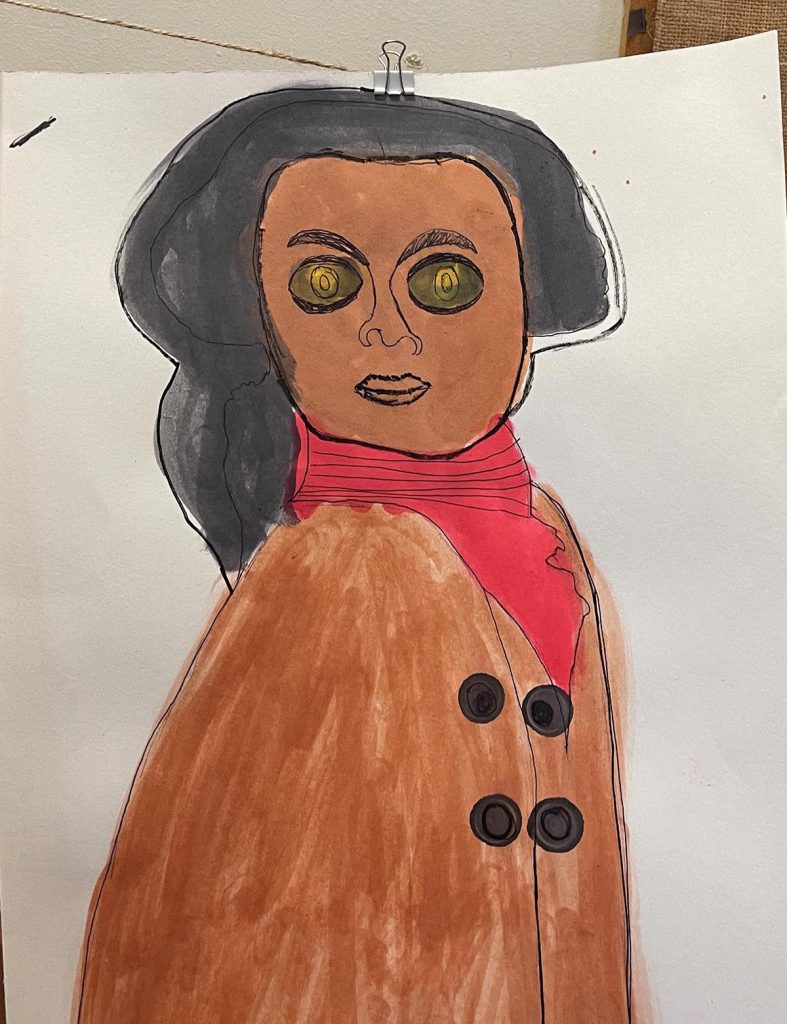

Young person’s drawing of Olaudah Equiano, a Black slavery abolitionist.

Enslaved as a child in West Africa, Equiano was shipped to the Caribbean and sold to a Royal Navy officer. He was sold twice more before purchasing his freedom in 1766.

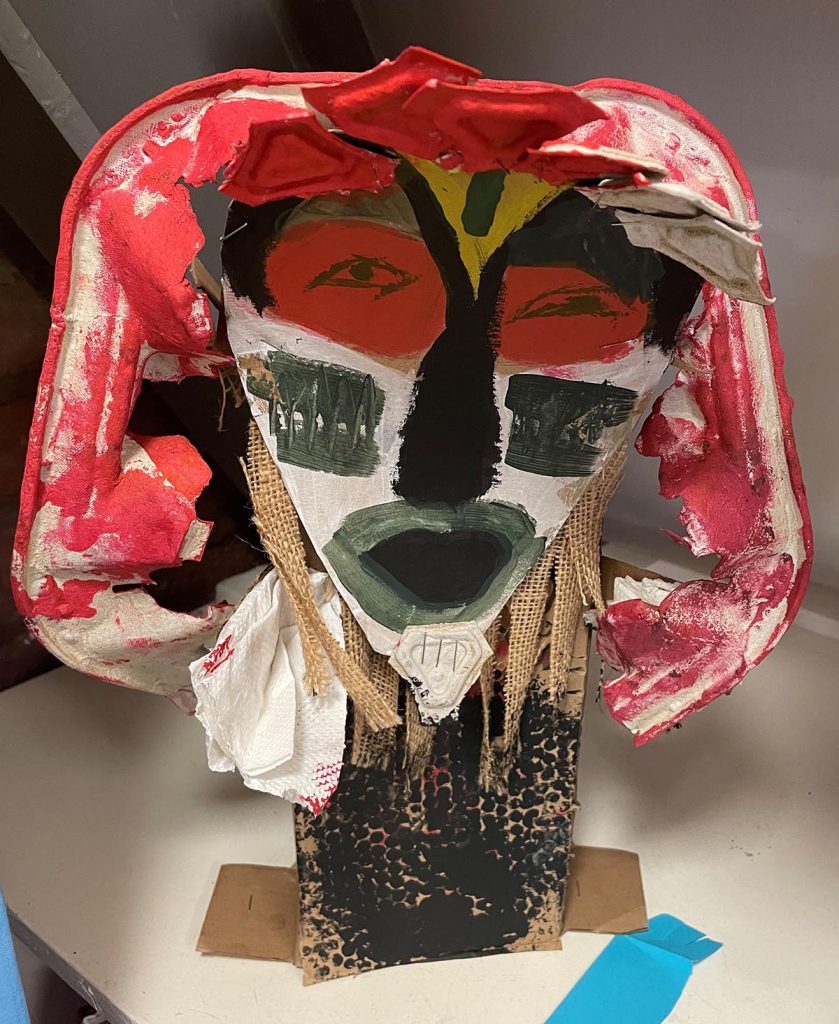

Young person’s creation of an African Masquerade.

Masquerades involve the wearing of masks and costumes to disguise one's identity and participate in performances that often have symbolic meanings.

My research also harnesses creative and participatory methods to inspire young people to imagine better outcomes for themselves – now, and in the future. I used Dixit, a card game that invites people to create imaginative stories, to prompt discussions about experiences of racism. Young people also used photos and videos to tell stories of their experiences, and to discuss the change they would like to see in the world. My hope is that by embarking on this imaginative educational journey, young people will raise their critical-race consciousness in ways that encourage them to start or join social and political action for positive change.

Some people suggest that direct action for change, such as anti-racist movements, are dividing societies. I argue that the division stems instead from the politics of fear and resentment that is ravaging our societies. Contemporary politicians and reactionary social movements are operating from positions of fear. To combat these threats to democracy, we need alternative visions of a better world fashioned from the dreams of young people, who have the potential to imagine a world radically different from the one they are inheriting.

To combat threats to democracy, young people must envisage a better world, radically different from the one they are inheriting

Unleashing young people's democratic potential fills me with hope that we can indeed create this better world. My educational outreach brings young people's democratic potential to the surface. It encourages them to conceive of the world as it might otherwise be. Whether on their own, as part of communities / movements or as institutional agents, young people need to learn that they have the power to bring about a future free from inequality and oppression. I genuinely believe that despite present injustices, such sorely needed democratic transformation remains possible.