Politicians communicate with their constituents every day, but what are they saying? E-newsletters allow MPs to send direct, unfiltered messages to their desired audience. Daniel Casey and Adam Ozer examine new datasets which allow researchers to access every e-newsletter sent by MPs in Australia and the UK

During election campaigns around the world, including in Australia, the US and Greece, people complain about the flood of spam emails from politicians. One US journalist complained 'Democracy doesn’t have to be this annoying,' but one person’s trash is another person’s research treasure. Here, we introduce CanberraInbox and UK MP Inbox, two revealing new datasets of all e-newsletters sent by members of the Australian and UK Parliaments.

Democracy requires a connection between the public and their representatives. Legislators need to listen to their constituents, but constituents should also listen to their representative(s). While there is significant literature on what political executives (Presidents and Prime Ministers) say, what ordinary legislators say to their constituents is often harder to study.

Traditional media largely ignore backbench MPs, and while social media offers MPs more control, their communication is nonetheless subject to the whims of the platform’s algorithm and business incentives. In contrast, e-newsletters allow MPs to send direct, unfiltered messaging and information to their desired audience.

E-newsletters allow MPs to send direct, unfiltered information to their desired audience, yet in an age of misinformation, the lack of any official public repository is cause for concern

What politicians say, and how they use their time or resources, is of public interest. However, there is no official public repository of legislators' e-newsletters. This is of growing importance in an age of mis- and disinformation; while social media can label or remove posts that are dangerous or misleading, this is not possible for emails.

Both datasets are inspired by the American repository DCInbox, which contains more than 200,000 US Congressional e-newsletters. CanberraInbox launched in March 2024 and has so far accumulated around 1,800 e-newsletters. UK MP Inbox started in December 2023 and has 5,400 e-newsletters. Both are updated roughly every week.

Strikingly, most MPs don’t send e-newsletters. In the UK, between November 2023 and May 2024, only 209 MPs (32% of the total) had sent at least one newsletter. There were similar patterns in Australia, where only 79 legislators (35% of all MPs) sent e-newsletters. Australian analysis shows that legislators in their first term, those in marginal electorates, and those elected under a candidate-centric system (House of Representatives) are more likely to communicate via e-newsletters.

In the UK and Australia, centre-right parties were more likely than centre-left parties to send e-newsletters

Both countries showed similar party differences. Centre-right parties (Liberal/National coalition in Australia and the Conservatives in the UK) were more likely than centre-left parties to send e-newsletters. In the UK, nearly 50% of Conservative MPs have an active newsletter, compared with fewer than 20% of their Labour counterparts.

During the recent Australian election, we closely monitored what MPs were writing. Some – usually those on the extreme right – focused exclusively on niche policy issues. Topics included 'men invading women’s sports and spaces', or anti-vax Covid conspiracy theories. Others focus almost entirely on local issues, ignoring their party and their leader as national polling kept getting worse.

As Liberals realised their leader (Peter Dutton) was unpopular, they sought to distance themselves from him and their party brand. Around 65% of coalition e-newsletters did not mention their leader at all! Labor MPs, by contrast, seemed happy to name Dutton. Indeed, Australian Labor Party (ALP) e-newsletters were more likely to mention him than they were their own leader, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese.

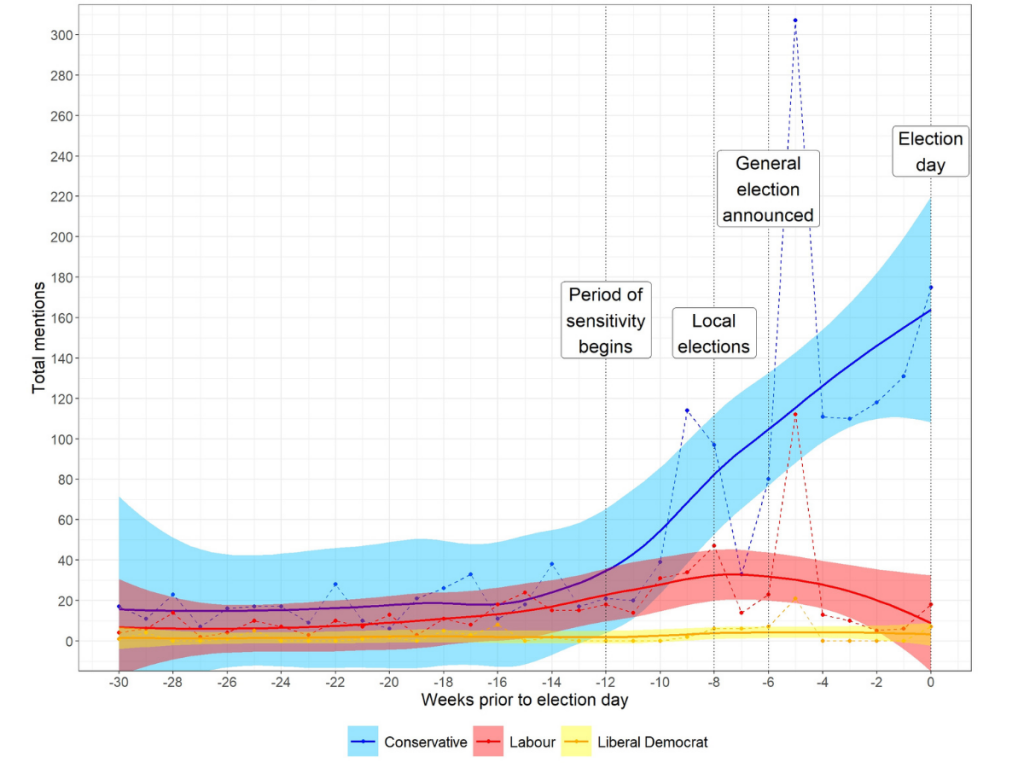

In the UK, uses of the word 'election' in e-newsletters show an interesting divergence in strategy. In the graph below, the dotted lines represent the total number of mentions of the 2024 elections per week. Solid lines represent the smoothed conditional mean (with a 95% confidence interval).

For all three parties, there was a pronounced spike in election discussion in the immediate aftermath of the general election announcement. However, while election discussions among Labour and Liberal Democrat MPs quickly return to their pre-election mean, Conservative MPs continued to discuss the election quite frequently until election day. This pattern fits with the prevailing narrative: while the Conservatives were seeking a key message that would minimise their electoral losses, Labour and Liberal Democrat MPs were content to remain relatively quiet to avoid anything that might undermine their projected success.

E-newsletters also allow MPs to express a little of their personality – not to mention their graphic design and Photoshop skills! They know that a funny Instagram picture or reel will get them more publicity than explanations of carefully designed policy. In Australia, Dan Repacholi (ALP, Hunter) is the master of this.

In one e-newsletter, Repacholi talked about a grant to upgrade facilities at a local Gymnastics Club, accompanied by this picture.

Repacholi is actually a former five-time Olympian – but in pistol shooting, not gymnastics!

Image source: CanberraInbox

And in one video, from which this is a still, he channelled the Austin Powers baddie Dr Evil to promote additional mental health funding and free vocational training.

Unfortunately, we are yet to find a UK MP who provides the same level of comedic entertainment.

Image source: Instagram

These datasets are growing, real-time corpora of elite political communication. Almost any political communication research questions could benefit from them. Policy scholars could use them to explore agenda-setting and framing, as well as differences between parties in communication and emphasis across specific policy areas. Such datasets could, for example, help analyse how different parties responded to the election of President Trump.

Our goal now is to explore the readership of e-newsletters to better understand how our democracies work. It is not clear how many constituents subscribe to these e-newsletters, although evidence from the USA indicates that 19% had signed up for an e-newsletter from their representative. Are subscribers more likely to participate in politics and write back to the legislator? Does it change their policy opinions or policy priorities? And most importantly for the legislator, does it influence their vote?