Winter is coming to Chișinău. On 1 January, Moscow cut off all gas exports to the former Soviet state of Moldova. John Chin and Noel Overby put this Russian energy embargo in the context of ongoing Moldovan resistance to a protracted Russian sharp power campaign

Moldovans are bracing for a 'harsh winter' and power cuts in 2025. On 1 January, Russia cut off all gas exports to Moldova piped via Ukraine and the breakaway region of Transnistria. Though Gazprom attributed the suspension to a debt dispute, Moldova’s prime minister Dorin Recean accused Moscow of using 'energy as a political weapon' in an attempt to 'destabilise Moldova'.

The people of Chișinău were expecting the gas cutoff. Previously totally dependent on Moscow for natural gas, Moldova has been diversifying energy sources since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022. At her second inauguration on December 24, President Maia Sandu, who won a close election in November, promised that 'light will prevail' over Russian blackmail. To prepare, Moldova declared a 60-day state of emergency on 12 December. Electricity prices have doubled in Moldova since then.

Moldova is a democratic David living in the shadow of Russia's Goliath

Moldova is a democratic David living in the shadow of Russia's Goliath. Like Romania and Georgia, Moldova is a frontline state in Russia’s near-abroad. It is a key target of a protracted Russian 'sharp power' campaign, and of Western counter-efforts at integration.

For the first decade of post-Soviet independence, Moldova’s fledgling democracy faced challenging conditions. Obstacles included a weak civil society, ethno-linguistic tensions between a Russophone east and Moldovan-speaking west, a hostile Russia backing Transnistria, aid dependence and low development levels (Moldova is Europe’s poorest country), no prior democratic experience, and no prospect of entry into the European Union. Yet a weak state and vulnerability to Western pressure resulted in 'pluralism by default'.

After winning the 2001 elections, Moldova’s communist party (PCRM) led by Vladmir Voronin returned to power. Though they increased control over state media and courts, PCRM ultimately failed to consolidate a competitive authoritarian regime. In 2002, pro-Romanian nationalists and students protested the 'Russification' of language policy. The PCRM yielded on language policy but kept office and won re-election in 2005.

The communists were finally ousted in 2009. After PCRM claimed 60 of 101 seats in the April 2009 parliamentary elections, fraud allegations triggered Moldova’s 'Twitter revolution', which was aided (if secondarily) by social media mobilisation. Some protesters raised EU, Moldovan, and Romanian flags outside parliament. Despite repression and lack of Western support, communists in parliament lacked a vote needed to elect a president. An opposition coalition won new elections in July 2009, and the Alliance for European Integration took power until, in 2013, a 'Pro European Coalition' replaced it.

Despite corruption and oligarchic control of politics in the mid-2010s, Moldova experienced a 'democratic U-turn' after 2018

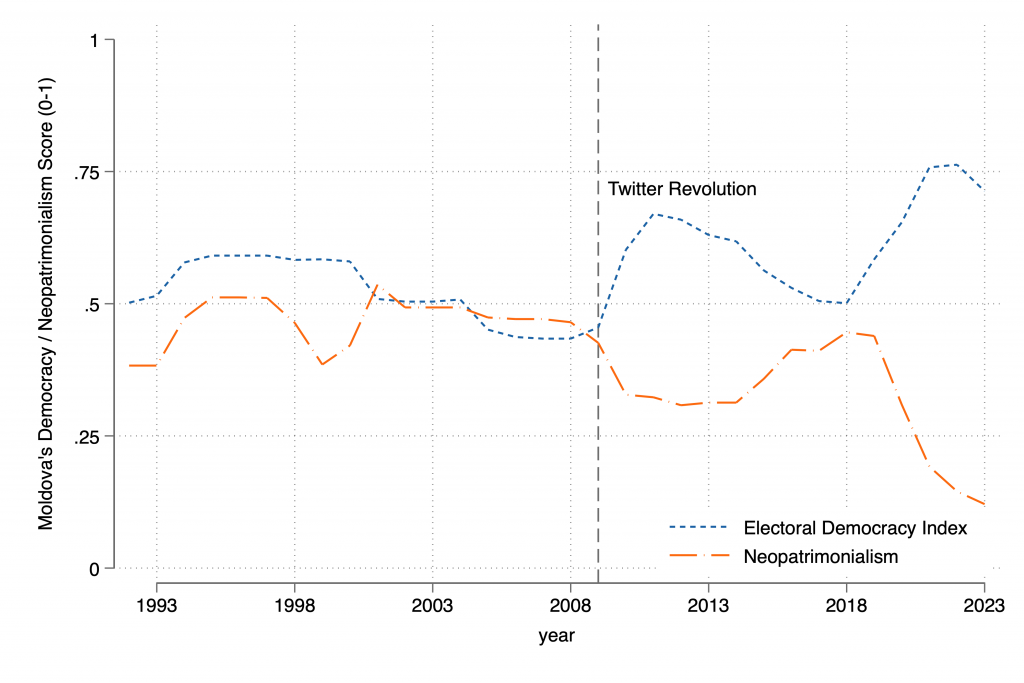

Moldova has experienced two waves of democratisation since 2009, per V-Dem data (see the graph below). Despite 'widespread corruption and oligarchic control of politics' causing democratic backsliding in the mid-2010s, there was a 'democratic U-turn' after 2018. In 2016, Moldova returned to semi-presidentialism. In 2020 and 2024, Maia Sandu of the pro-European Party of Action and Solidarity (PAS) won close presidential elections.

Yet Moldova’s democratic consolidation is incomplete, despite efforts to implement reforms needed to open EU accession negotiations. Moldovans lack trust in government institutions and remain divided over the Twitter revolution’s legacy. Sandu hailed it, while pro-Russian ex-president Igor Dodon has decried it for turning Moldova into a 'colony'.

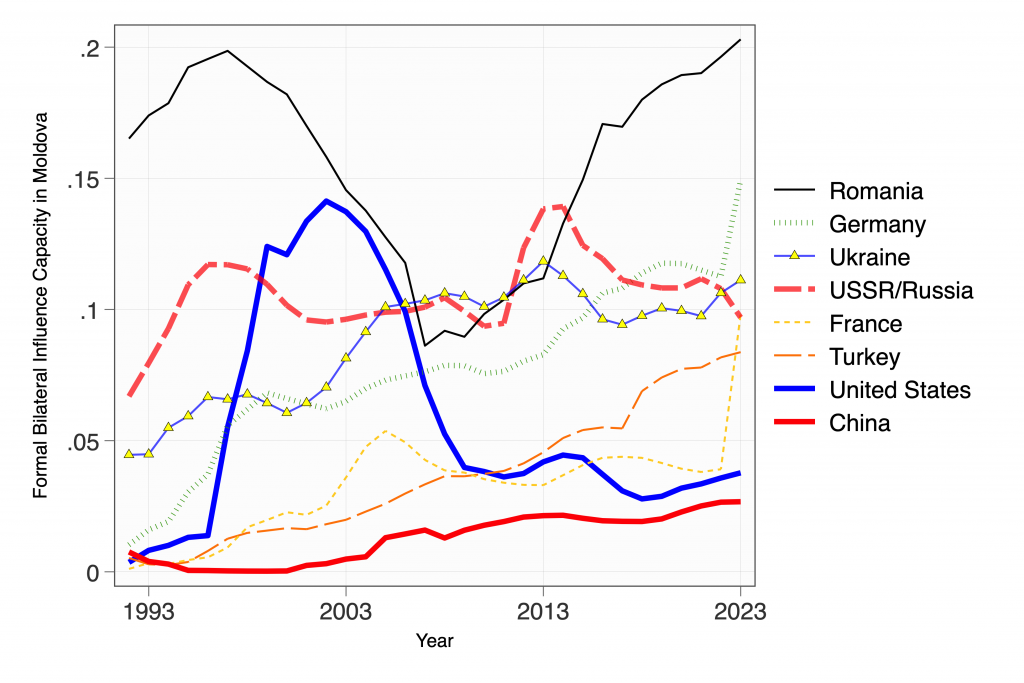

Moldova is pulled in multiple directions. Neighbours Romania and Ukraine have the most influence capacity in the country, as do European powers Germany and France. Yet Russia has retained significant, if reduced, influence capacity in the country since 2014, per FBIC data. US influence capacity in Moldova peaked two decades ago; China’s has gradually increased from low levels as trade has increased:

A significant portion of Moldova’s population shares cultural ties with Russia, and Russian influence in Moldova has its roots, in part, in ethno-linguistic affinity. Russia also gives financial and political support to separatist Transnistria, including maintaining troops in the region and (until last week) providing free energy that could be sold to the rest of Moldova. Russia’s strategic goals include undermining Moldovan support for NATO and the EU. As Moldova integrates west, Russia has responded with disinformation campaigns, cyber-attacks, and election interference. In early 2023, Ukrainian intelligence uncovered a coup plot in Moldova masterminded by the Wagner Group.

Russia’s strategic goals include undermining Moldovan support for NATO and the EU

After Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Moldova’s PAS government applied for EU membership and has resisted Russian sharp power. In March 2024, France and Moldova signed a defence pact amid fears of Russian aggression. President Sandu then scheduled a referendum on EU accession in October 2024, to coincide with presidential elections. As evidence mounted of a Russian plot to interfere, Moldova responded by blocking access to over 20 Russian websites and Meta dismantled a network of fake news accounts targeting Russian-speaking Moldovans.

The West has helped Moldova counter Russian sharp power through assistance diversifying energy resources, providing non-lethal aid, supporting counter-intelligence operations, and expressions of diplomatic support. For example, US Secretary of State Antony Blinken visited Chișinău in May, and the US committed $135 million in aid. Then in June, the now-defunded State Department Global Engagement Center helped uncover a Russian disinformation campaign in Moldova, including Russia Today’s covert support to pro-Russian oligarch Ilan Shor. Shor, one of Moldova's most popular politicians, was accused of recruiting people to vote for minor candidates against EU integration.

In the landmark October 2024 referendum, a slight majority (50.4%) of Moldovan voters backed inclusion of EU membership in Moldova’s constitution. A joint statement of support for 'Moldova’s success in thwarting Russian destabilisation efforts' and commitment to taking 'its rightful place within a free and democratic Europe' was signed on 8 November by the leaders of France, Germany, Italy, Poland, Romania, the United Kingdom, the European Council, and the European Commission.

Moldova, which does not yet meet EU membership criteria, has targeted joining the EU by 2030. EU membership appears a strategic necessity for both Moldova and the EU.

Whatever happens, Moldova’s democracy and future in Europe are at stake in the ongoing battle over whether a European spring follows Moldova’s harsh Russian winter.