The sometimes inflationary use of ‘populism’ has prompted calls to discard the term altogether. Bartek Pytlas argues that what we need instead is a more differentiated and dynamic approach to populism – one that involves contrasting populism against other ideas, as well as observing how political actors use these ideas in practice

Mattia Zulianello and Petra Guasti invite us to take a fresh look at a long-overdue debate on how to approach the often (over)used term populism. As ‘populism’ becomes a buzzword in public and academic discourse, we should remain wary of its inflationary uses. By overemphasising populism, we risk overlooking or misidentifying other important phenomena behind today's increasingly turbulent politics. These include ‘thick’ ideologies such as nativism, and different ‘thin’ ideas on what constitutes ‘good representative politics’, such as non-political expertise or political will.

The inflationary use of ‘populism’ has revived proposals to discard the notion altogether. While I understand this perspective, I do not think that scrapping populism is the ideal solution. The discursive impact of populism is too extensive, and the related matters such as democracy too relevant, to simply ignore. Populism therefore remains important both as a concept and as part of several parties' rhetorical toolbox.

I suggest we need a more differentiated and dynamic approach to populism. We need to be clear not only where populism begins, but also where it ends

What we need instead, I suggest, is a more differentiated and dynamic approach to populism. We need to be clear not only where populism begins, but also where it ends. Accordingly, we must contrast populism with ‘thick’ cultural and economic ideologies, and different ‘thin’ ideas on representative politics and democracy.

In addition, we must account for the flexible and sometimes paradoxical ways parties use these distinct ideas in practice. It is therefore important to look beyond mere populism and to embrace the chamaeleonic character of anti-establishment politics. By so doing, we might better understand specifically when and how populism can play into contemporary political turbulence.

We have already gained important insights into populism's key features. But we should focus more on contrasting populism with other ideas. There is growing awareness that we must avoid conflating primary cultural and economic ideologies with thin ideas like populism. As Zulianello and Guasti note, overemphasising populism can lead us to underestimate the key relevance of core ideologies. One example is the crucial role of nativism for the radical right.

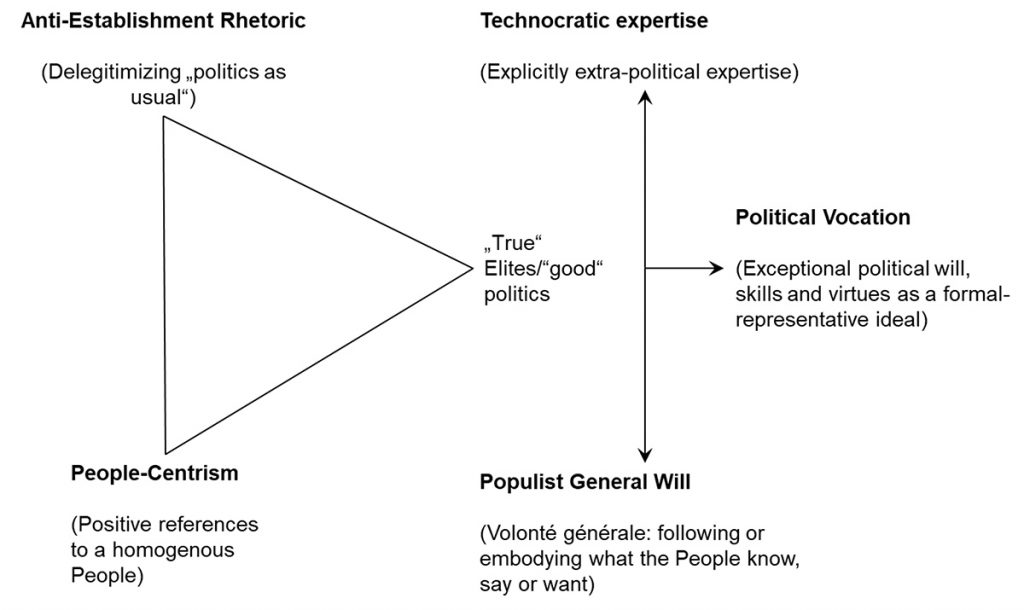

Concurrently, we should also be wary of conflating populism with other thin notions of 'good representative politics' or 'true elites'. While populist politics is always anti-establishment, not all anti-establishment politics is (solely) populist. Political parties do not only link a fundamental ‘people-elite’ conflict to the idea that politics should be bound to or embody infallible popular will.

Once we account for various thin ideas beyond just populism, it turns out that over the last decade, anti-establishment parties across the ideological board have contested conventional politics from different, sometimes surprising, angles. In addition to – or often even instead of – extensive appeals to populist general will and technocratic extra-political expertise, they have increasingly enacted an extraordinary political vocation: exceptional political will, skills and virtues presented as necessary to ‘revive’ formal-representative politics itself.

The Italian Five Star Movement (M5S), for example, stated that: ‘The big difference between us and them is that in M5S there is, and always will be, political will’. In France, Emmanuel Macron called for reinvigorating political life which was to ‘remain a vocation and not a profession’. Particularly after 2015, several other less or more established actors such as the radical-left Podemos in Spain, but also the radical-right FPÖ in Austria, used strong appeals to formal-representative skills and competence, embracing competition logic typically reserved for conventional parties.

So, populism is not the whole story. For example, once we focus on different ideas of representative politics, it turns out that populism is not a universally effective ‘thin’ mobilisation strategy, all else being equal. Anti-establishment parties which use more populism do not perform better electorally than those which rely on it less.

Anti-establishment parties which use more populism do not perform better electorally than those which rely on it less

Instead, anti-establishment parties across the political board benefited more when they emphasised their appeals to political vocation, promising to revive an imagined ideal of conventional, formal-representative politics itself. We should thus be careful not to view the electoral gains of every anti-establishment party as a success of ‘populism’.

Being clearer about populism's contours helps us address another challenge mentioned by Zulianello and Guasti: populism's chamaeleonic character.

Recognising that populism is not the whole story invites us to embrace the populist ‘chamaeleon’. Acknowledging that not all anti-establishment parties are populist helps to grasp the flexibility of anti-establishment and populist politics in parties.

We should see the chamaeleonic character of anti-establishment politics not as a ‘bug’ but as a feature

Rather than simply looking at whether parties use less or more populism, these combined perspectives allow us to assess how parties can combine and meander between distinct thin ideas and strategies in practice. This encourages us to see the chamaeleonic character of anti-establishment politics not as a ‘bug’ but as a feature.

In no way does this question the importance of identifying varieties of substantive ideological and systemic party characteristics. In times when radical-right politics in particular has become increasingly normalised, it is important to contrast parties’ political rhetoric with substantive ideas. Observing how parties combine different ideas and strategies allows us to assess how radical parties rhetorically navigate appeals of both distinctiveness and ‘normality’ behind their often unchanged substantive positions. It can also help us to explore intra-party conflict and competition between ideologically similar actors within a single party system.

A more differentiated and dynamic approach helps to identify specifically when and how populism might play into current political turbulence. Paradoxically, in order to get the most out of ‘populism’, we need to look beyond populism alone.

Fourth in a Loop thread on the Future of Populism. Look out for the 🔮 to read more