Evidence shows that young people make productive legislators who work hard and get reelected. With elections to the European Parliament imminent, voters have a chance to significantly boost youth representation in European politics. Michal Grahn argues that youth representation matters because young people are growing increasingly disillusioned with democracy

Young people are significantly underrepresented at all levels of European politics. Although one in five European Union citizens are aged 18 to 35, only 6% of MEPs come from this age group. In contrast, individuals aged 51 to 61 also make up 20% of Europe’s population, yet are represented by 42% of MEPs. Interestingly, the number of MEPs under the age of 30 is the same as the number of MEPs named Martin — six.

In national politics, less than 4% of legislators are younger than 30. With an election superyear underway in Europe, voters have a unique opportunity to enhance the representation of young people in elected office by voting for young candidates. Along with the European Parliament elections, voters are heading to the polls in Iceland, Belgium, Croatia, Austria, Georgia, Lithuania, and the United Kingdom.

| Region | Chambers | Seats | % aged 30 or under | % aged 40 or under | % aged 45 or under |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Americas | 34 | 4,594 | 3.61 | 22.86 | 36.00 |

| Middle East and North Africa | 16 | 2,774 | 2.20 | 16.40 | 29.20 |

| Europe | 64 | 12,699 | 3.56 | 20.60 | 33.92 |

| Pacific | 13 | 679 | 1.62 | 12.96 | 23.71 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 35 | 4,912 | 2.30 | 21.82 | 37.85 |

| Asia | 36 | 6,911 | 2.11 | 12.89 | 24.74 |

Why is the absence of young perspectives from political decision-making a problem? Parliaments that lack young voices are likely to produce policies that fail to consider or advance young people's interests. This oversight threatens to undermine the legitimacy of democratic decision-making. It also risks exacerbating young people's growing sense of alienation and disenchantment with democracy.

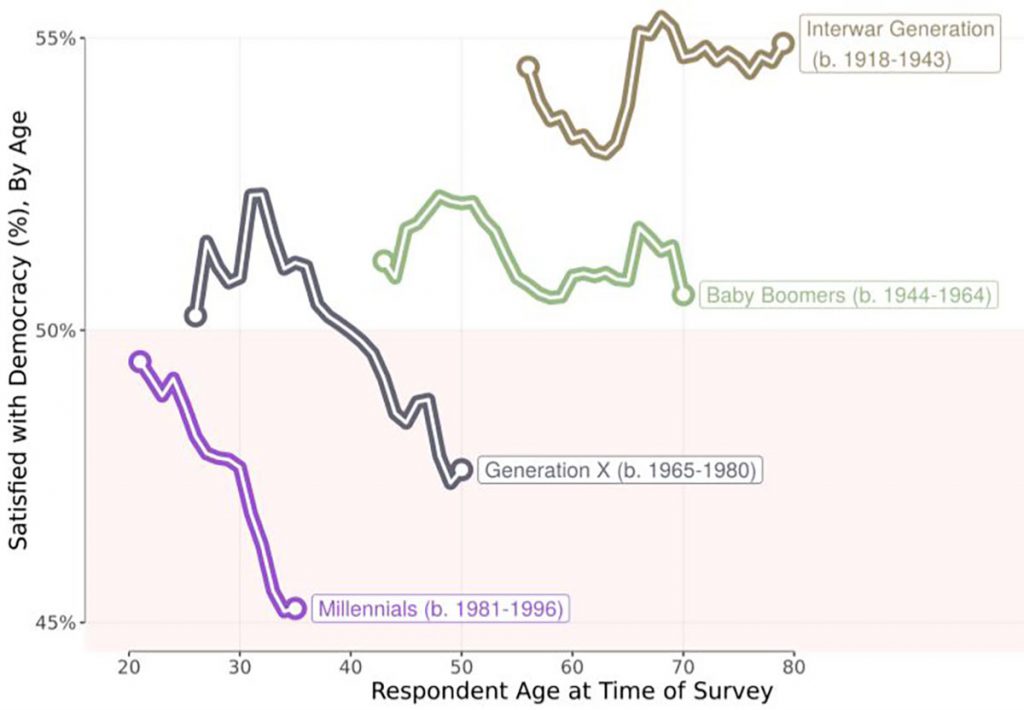

A 2020 University of Cambridge report shows that, across the world, satisfaction with democracy is in steepest decline among 18–34-year-olds.

Recent analysis by The International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance suggests that young voters may be fuelling the growth of far-right movements. This may be, in part, because they feel mainstream parties do not represent the interests of their age group.

Electoral disillusionment among young voters may be inadvertently fuelling the success of far-right movements

The absence of young candidates and legislators signals that politics is ‘off limits’ to young people and their perspectives. The lack of young politicians thus has symbolic effects among young people on their disillusionment with democracy.

A new wave of research is investigating why young people are often absent from the corridors of power. Importantly, this research finds no evidence that voters are inherently biased against young candidates. Instead, it seems the scarcity of young politicians stems from a reluctance among political parties to nominate young candidates.

Young aspirants often do not fit the traditional image of an ideal politician: a middle-aged, white-collar, married man of the majority race and religion. Voters also tend to regard young candidates as being more ideologically extreme. This, of course, can raise concerns about their adherence to the party line. Such stereotypes may therefore complicate matters for the few young candidates who do get elected.

There is no evidence that voters are biased against young candidates – there is, however, a reluctance among political parties to nominate them

Political parties are the primary gatekeepers to essential sources of political capital and political career opportunities. This includes access to setting the political agenda, positions on influential committees, and resources like skilled staff, polling data, and peer mentoring opportunities. The allocation of this capital is crucial for determining an MP’s success or failure.

In essence, the impact that young MPs can have in the legislative domain, particularly in advocating for policies that affect young people’s lives, depends significantly on the support and opportunities provided by their parties.

My recent research analyses data from all MPs elected to the Czech Parliament over the last three decades. As is the case in many other countries, young people are underrepresented in Czech politics. On average, legislators who are 35 years or younger comprise only 12% of the legislative body.

Some young individuals, against all odds, do manage to navigate the candidate recruitment process and get elected. My findings show that these individuals often receive apprentice-like treatment from their party peers.

Young Czech MPs are treated to a kind of apprenticeship from their more experienced party peers

In the Czech Republic, young MPs receive privileged access to tasks and responsibilities that improve their understanding of the legislative arena and its intricate rules. They participate in more select committees and co-sponsor more bill proposals than their more experienced colleagues. Thus, they benefit from a form of peer mentorship that nurtures their political careers.

I also find that young MPs are more likely to be renominated and reelected by their parties. By the time young MPs enter the legislative arena, they are well positioned for successful political careers. Political seniority, a critical prerequisite for agenda influence, is within their reach.

As the EP elections approach in early June, voters have a chance to advance young candidates. Twenty-one of the EU’s twenty-seven member states use electoral formulas that allow voters to indicate preference for individual candidates, regardless of where they appear on the ballot. By indicating preference for young candidates, voters can significantly boost the presence of young people in the EP. Given the generally low voter turnout in many EU member states, even a marginal coordinated vote can make a difference.

Once elected, young MPs are unlikely to disappoint.