Minority governments are generally disdained in most parts of Europe. They're seen as a second choice to majority governments which are assumed to be more stable and effective in policy-making. Yet, argue Svenja Krauss and Maria Thürk, there is more than one type of ‘minority government’. Some variants can match majority governments in both stability and effectiveness

After the 2017 German federal elections, Angela Merkel dismissed the idea of forming a minority cabinet. She claimed her goal was to build a stable government with capacity to enact policies. In so doing, she tapped into one of the great conventional wisdoms among most European publics and politicians, as well as of political science: that minority governments are less stable and less effective in policy-making than majority governments.

Scepticism about minority governments has especially deep roots in Germany, Belgium, Austria, or the UK. This is often linked to historical legacies (in the German case, the instability of the Weimar Republic). But scepticism can be an important driver in government formation.

conventional wisdom says that minority governments are less stable and less effective in policy-making than majority ones

It is high time we challenge conventional wisdom on minority governments. And that's what we do in our new article in West European Politics.

In the article, we make a distinction between different types of minority cabinets. When you think of minority governments, you usually think of the 'classic' or 'genuine' type. That is, a minority in office looking for partners on an ad hoc basis for (almost) every policy proposal, to build parliamentary majorities. This is what Strøm called substantive minority governments. It's reasonable to assume that such governments are less stable than majority ones insofar as they are prone to regular parliamentary defeat.

However, there is another type of minority government that, in contrast with substantive minority governments, works with permanent support partners. These formal minority cabinets work on the basis of long-term support agreements that provide the minority cabinet with legislative security. This is because their partner(s) vow to support the minority cabinet on crucial votes (e.g. confidence votes and budget votes). In exchange, the minority cabinet makes policy concessions to its support party.

We argue that these support relationships stabilise the minority cabinet if they are based on a public and written agreement since it is the most institutionalised form of government-opposition cooperation.

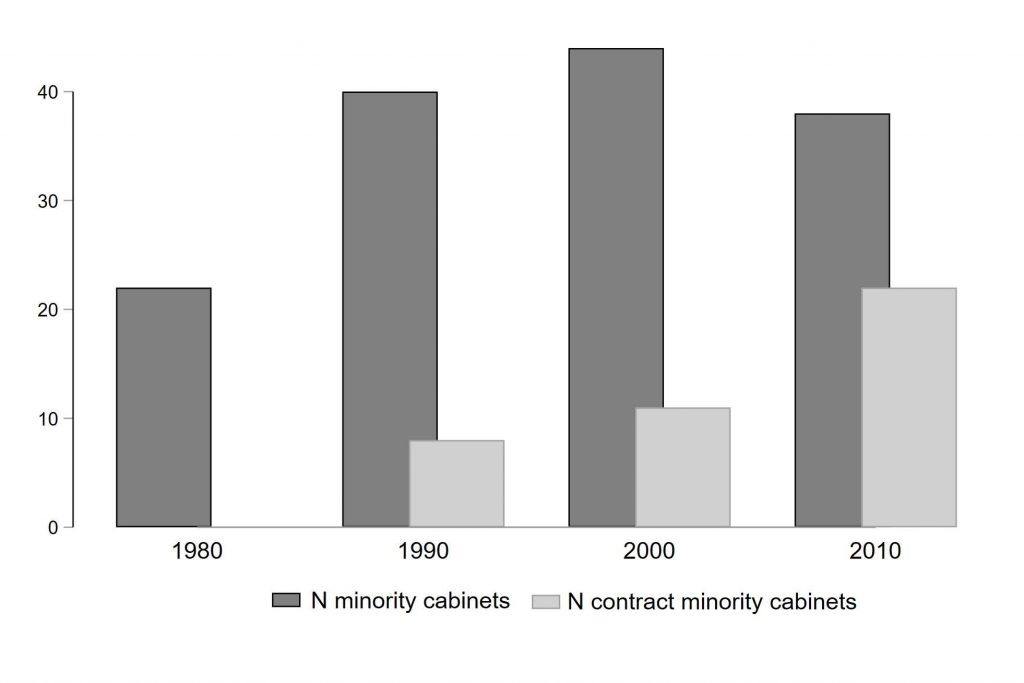

Our data show that this type of contract-based minority cabinet has become more popular over the decades (see Figure 1). In fact, more than half of all minority cabinets in the 2010s were contract minority ones. While written support agreements were the exception 30 years ago, nowadays we even find them in Denmark – the textbook example of substantive minority governance.

So, what is the effect of these different types of minority cabinet on government duration? We argue that contract minority cabinets share more attributes with majority coalitions than with substantive minority cabinets. Our rationale is that both sides – minority cabinet parties and their support parties – have committed publicly to their mutual agreement. Hence, the support party is unlikely to risk losing policy benefits by betraying the minority cabinet, or losing institutionalised cooperation by behaving in a way that brings down the cabinet.

contract minority cabinets share more attributes with majority coalitions than with substantive minority cabinets

Consequently, we hypothesise that only substantive minority cabinets are less stable than majority ones. Contract-based minority cabinets, we find, are just as stable as majority ones.

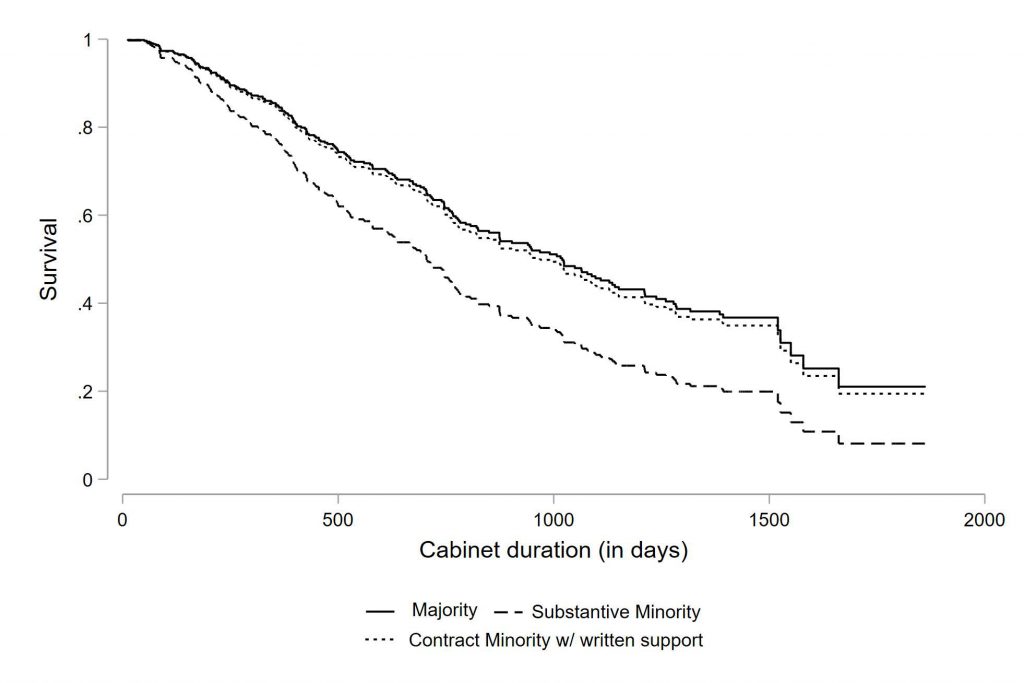

Our analysis of 471 governments in 30 countries since 1977 supports this argument. The data confirms that substantive minority governments are less stable than majority ones. But we find no difference between contract minority and majority cabinets.

Figure 2 displays survival rates for majority, substantive minority, and contract minority cabinets. Survival rates for majority and contract minority governments are virtually the same; those for substantive minority governments significantly lower. This suggests that minority governments can essentially work in a similar way to majority governments if they have a permanent support partner, at least from the perspective of their prospective duration. In such cases, they are effectively 'majority governments in disguise'.

What does this tell us, then, about the practicability of minority governments? What kind of advice would we give to policy makers?

Minority governments should be considered more seriously as a viable option. They can be not only as stable as majority governments, but also effective with regard to policy-making and pledge fulfilment. Formalised written support agreements can provide a stable environment for minority cabinets, even if a country has little experience of minority governments.

Minority governments should be considered more seriously as a viable option

However, there is one important caveat to consider, especially in countries with little or no experience of minority government: it takes a specific kind of political culture to work. A certain level of willingness to cooperate is necessary from most (if not all) parties in parliament. Parties in government must be prepared to make policy concessions, and those in opposition parties must behave constructively.

Are you listening, Angela?