Party-based regimes are the most durable autocracies. Although there exist stronger and weaker ruling parties depending on the elite-leader relationship, the attitude of party-based regimes towards citizens also matters to their nature. Fabio Angiolillo argues that ruling parties’ recruitment strategies in autocracies can facilitate a much deeper understanding of party-based autocracies

Political parties are one of the fundamental institutions in any political system. In studying autocracies, previous literature has highlighted ruling parties’ importance for elite-leader bargaining power. There is general agreement on their importance for autocracies. However, to understand authoritarian ruling parties’ differences and similarities, we must move away from the popular elite-centric approach. Instead, we should look at the strategies such parties use to engage with citizens. In doing so, we can explore how they institutionalise their authoritarian successes and why citizens support or oppose them.

This Autocracies with Adjectives series shines a light on the political dimensions still underexplored in autocracies. Political parties’ internal structures have been conspicuous by their absence, despite their central role in the stability of dictators’ regimes.

Party-based regimes are the most durable autocracies. Researchers still grapple with questions related to how to distinguish strong from weak ruling parties. The primary debate looks at the origins of such parties and their institutional structure to define their strength from an elite politics standpoint. According to this approach, parties are only functional to power-sharing dynamics among elites. However, the approach struggles to unpack differences in ruling parties’ internal organisation and, consequentially, to define their roles to shape their strengths.

Elites and leaders hold the highest political powers in autocracies, and are therefore important for us to study. Yet they are also the smallest section of the ruling party in absolute terms. Hence, we must explore different levels of the ruling parties’ structures to define differences and similarities within party-based autocracies.

Elites and leaders hold the highest powers, yet represent the smallest section of the ruling party. Hence, we must explore different levels of ruling-party structures

Political parties seek new members, and these come from the population. Thus, the connection between ruling parties and citizens can take different turns depending on how elites outline their recruitment strategies. Party-based autocracies are among the most durable regimes. This is because a ruling party enables repeated interactions between elites to bargain over power-shares.

I argue that this is not the only reason for their durability; party-based autocracies have the most direct contact with citizens because there exists a ruling party actively involved in securing legitimacy and co-optation from the population.

The Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) and the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) in Mexico are among the strongest ruling parties. They share similar origins and efficient institutional structures. CPSU and PRI are both highly durable, and previous literature defines them as 'strong parties'.

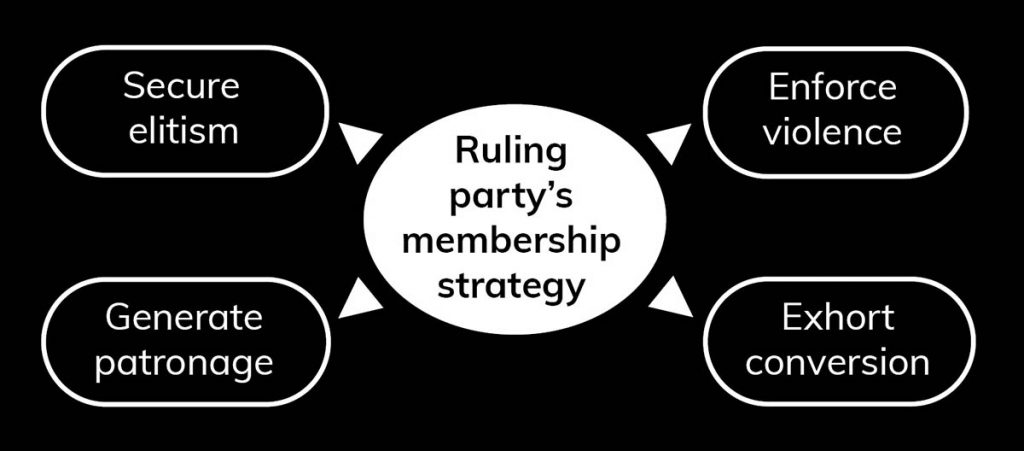

However, looking at their membership strategies, they are divergent cases. Following a Leninist organisational structure, CPSU required high ideological commitment to its members; membership was a privilege that granted considerable returns compared with non-members. CPSU’s membership strategy, therefore, was to secure elitism (or vanguard). By contrast, the PRI lacked a stringent ideological line to its members. Instead, it interpreted its role in society in terms of generating patronage. Access barriers to the PRI were looser, and it had a broader party membership base.

Once we scrutinise these differences, we can spot other strategies for engaging with the population. Ruling parties can inspire loyalty. They can also impose violent rule, and establish armed groups to eliminate potential opponents among citizens. Two such outstanding cases are Germany's National Socialist German Workers' Party (NASDP), their Schutzstaffel (commonly known as the SS), and the paramilitary wing Sturmabteilung, or SA. The Communist Party of Kampuchea with the Khmer Rouge under Pol Pot is another example.

Ruling parties can gain new members through violence or exhortation. The latter relies on subtle mechanisms such as populistic rhetoric rather than physical threat

Ruling parties can also aim to gain widespread legitimacy among citizens by exhorting conversion. Their aim is to get as many citizens as possible to become party members. While the outcome of both enforcing violence and exhorting conversion is a massive membership base, the latter relies on subtle mechanisms such as populistic rhetoric over physical violence. As an example, in 2013, the PSUV in Venezuela engaged in the biggest membership recruitment campaign in any autocracy over the past two decades, in which Hugo Chavez’s face was associated with the slogan 'those loving [our] country, join me!'

What do these strategies imply for authoritarianism? Recruitment strategies define party-based autocracies in different sub-typologies. And this implies that the value of party membership can be different. Citizens living under a ruling party that implements an elitist recruitment strategy would regard a party membership card as a valuable asset. Imposing party membership on virtually every citizen by force, on the other hand, would diminish the value of membership.

Recruitment strategies define party-based autocracies in different sub-typologies, implying that the value of party membership can be different

This logic shapes deep differences in citizens’ perception of ruling parties, which can influence their support for autocracy, too. Citizens’ political behaviours and positions shift in reaction to changes in these parties’ strategies for engaging with their population, possibly shifting their support to opposition. As an example, in the 1970s, an increasing number of party members grew dissatisfied and challenged the CPSU, returning their membership cards to their party branches.

Ruling parties’ membership strategies have implications for how citizens engage with a seemingly identical institution: ruling parties. Previous blogs in this series have already raised important questions about how to classify and measure some institutions. Hence, future research should attempt to incorporate membership strategies in the study of ruling parties. Scholars should measure regime typologies using the ruling party as authoritarian institution.

Through this approach, we will be better equipped to classify ruling parties’ strengths and their effective value for authoritarian regime typologies. This bottom-up view will usefully complement the well-established elite politics perspective.