We associate authoritarian regimes with certain policies. However, the relationship between regime type and policy is not straightforward – and not all transitions towards authoritarianism bring policy change. To better understand this, Emilia Simison suggests paying attention to differences within authoritarian regimes and how the adjectives of autocracy affect policy

Regime transitions raise fears and expectations of policy change. We expect coups d’état, for example, to radically change the political game and bring deep changes in public policy. After all, dictators have different governing styles and goals than democratic rulers, right? However, history shows that policy has not always changed following a regime transition. And, in fact, the evidence linking regime type and policy is far from conclusive.

To explain such inconclusiveness, we must turn our attention from the differences between autocratic and democratic regimes to the differences that exist within each of these broad regime categories. As Hager Ali and Catherine Owen argue in their contributions to this series, there are multiple types of authoritarian regime and autocratic public policy. Thus, we cannot always expect the implementation of an authoritarian regime to have the same effect on policy.

Instead, the specific characteristic of each authoritarian regime determines how – and to what extent – the regime affects public policy. The vast academic literature on regime type and policy identifies a range of mechanisms linking the two. For instance, the existence of elections, political competition, and popular mobilisation have been used to demonstrate policy differences between authoritarian and democratic regimes.

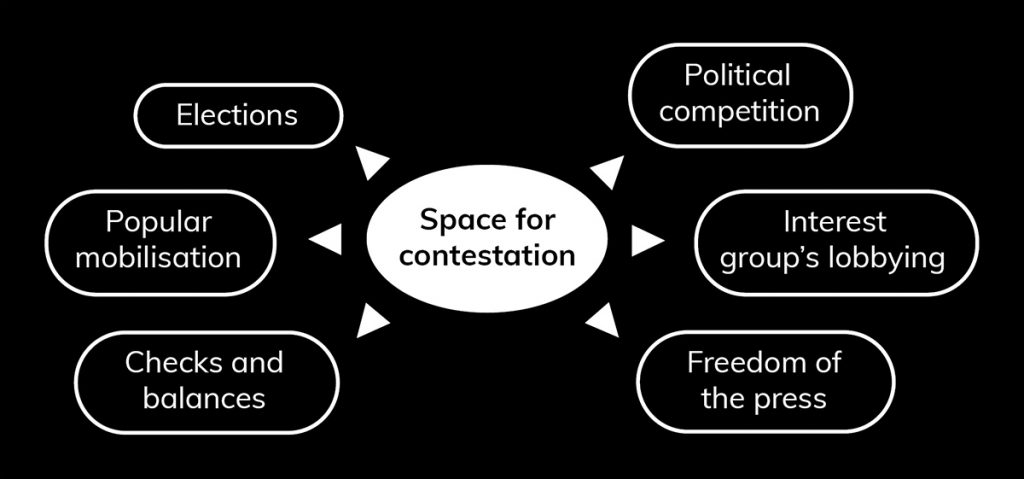

My work argues that the characteristics of the regime determine which of these links affects policy. When analysing policy, we can describe a regime using six different dimensions of what I call the space for contestation over policy – see the graphic below. Authoritarian regimes tend to constrain such space for contestation. However, they do so in different ways and to different extents. Hence the adjectives. There are electoral authoritarian regimes, single-party regimes, personalistic regimes, mobilising authoritarian regimes…

To explain policy differences across autocracies, we should examine the ways each authoritarian regime constrains the space for contestation

I argue that the adjectives of an authoritarian regime affect the evolution of policy. If elections are held, they will likely affect policy; if some level of political competition is allowed, that will also likely affect policy. Thus, to explain policy differences across autocracies we should pay attention to the specific ways in which each authoritarian regime constrains the space for contestation.

Let’s explore this idea with some concrete cases. In my book project, I study the evolution of policymaking and outputs in three different authoritarian regimes: the Brazilian military regime (1964–1985), and two Argentinean military regimes, the Revolución Argentina (1966–1973) and the Proceso de Reorganización Nacional (1976–1983). All three regimes held power roughly in the two decades between 1964 and 1985. They were military in nature, and ruled over countries with a similar cultural and historical background. However, they constrained the space for contestation in markedly different ways.

We can explore such differences using the dimensions of the space for contestation. Elections were suspended in the Argentinean cases but remained relevant for subnational and legislative positions in Brazil. The Brazilian regime allowed for some level of legal political opposition, while the Argentinean regimes did not.

The presence of legislatures in authoritarian regimes provides some check on the Executive, as well as an arena for interest-group lobbying

Attempts to constrain popular mobilisation, and their success, were greater in the second Argentinean regime than in the other two. This regime also severely constrained the freedom of the press. By contrast, the Revolución Argentina did that to a far lesser extent, and the attitude of the Brazilian regime towards the press changed over time.

The regime of Revolución Argentina concentrated power in the office of president and allowed for greater personalisation of power. The other two regimes actively prevented such personalisation. The presence of legislatures in these two cases – appointed in Argentina in the 1970s and elected in Brazil – provide some check on the Executive, as well as an arena for interest-group lobbying.

Do these differences matter? They do if we care about policy. Housing policy offers a clear example. In both Argentina and Brazil, the military coups took place in contexts characterised by emergency legislation on urban leases. Policies such as rent freezes and bans on evictions had been the norm for decades. The three military regimes had among their explicit goals to put an end to such policies. Despite the shared goal, the resulting policies varied widely.

In the 1970s, the Argentinean military regime implemented a new urban lease law shortly after the coup. This law eliminated rent freezes and eased evictions. It also restricted future interventions by the Executive.

In Brazil, the Executive drafted a similar legislative proposal. However, given the institutional design of the regime, such a draft needed to be discussed in Congress. This implied a longer lag between the coup and the implementation of the policy. More importantly, the proposal was modified in Congress by legislators worried about elections and / or standing in opposition to the regime. The resulting law was less restrictive than the Argentinean one. Elections and checks and balances mattered.

Popular mobilisation, in turn, explained the failure of the previous Argentinean military regime in enacting its preferred legislation. Faced with popular discontent and mobilisation, the regime only implemented partial laws and was even forced to backtrack shortly after implementing them.

Studying how, and how far, an autocracy constrains the space for contestation over policy helps us refine our expectations regarding policy change

As this blog series shows, autocracies differ from each other. Such differences matter. They matter not only for mere purposes of academic classification, but because of their concrete empirical consequences. The evolution of policy in an autocracy depends on this autocracy’s adjectives. Paying attention to the way and the extent to which an autocracy constrains the space for contestation over policy offers us a way to refine our expectations regarding policy change. More importantly, it gives us tools to affect the evolution of policy, even in authoritarian regimes.