International organisations are being challenged from two sides. Weak and rising states are demanding more influence, while declining Western powers turn away from institutions they helped to create. Benjamin Daßler, Tim Heinkelmann-Wild, and Martijn Huysmans argue that institutional rules can help balance power relations and stabilise international cooperation in times of power shifts

International organisations (IOs) such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Trade Organization (WTO), and the World Health Organization (WHO) often appear to be chess pieces in a grand geopolitical game, manipulated by their most powerful members. It is tempting to conclude that IOs are puppets of great powers, while weaker states are left voiceless.

Our research challenges this view and uncovers how IOs balance the scales. When major IOs were established after the Second World War, their founders implemented legal safeguards into their contracts. In so doing, they created an institutional power equilibrium that balanced the interests of powerful and weaker states. But power is now shifting, and IOs must reform to reflect new realities.

Materially powerful states typically lead the creation of IOs, and shape their operation. Their influence can rest on formal rules, such as weighted votes. It may also depend upon informal channels, such as privileged access to IOs’ bureaucracies or their superior ability to organise majorities.

But why should weaker states then participate in IOs? How can they be confident that they will benefit from multilateral cooperation? We argue that the institutional power equilibrium at the core of IOs’ design offers an explanation. Powerful states incorporate legal safeguards into IOs’ founding contracts to gain the support of weaker states. After all, while powerful states seek to retain as much control over IO decision-making as possible, cooperation without the voluntary participation of weaker states tends to be less effective and legitimate.

Why should weaker states join international organisations? How can such states be confident they will benefit from multilateral cooperation?

Two mechanisms are key in gaining weaker states’ support for IOs. First, veto rights offer states the power to block decisions they view as harmful to their interests. Such rights provide even weak states with the credible option to block IO decision-making and ask for concessions by the powerful. Second, exit clauses allow states to withdraw from an IO if they feel it no longer serves their interests. As exit clauses make membership termination by weak states more credible, they also bolster their bargaining power in IOs.

To illustrate this careful balance between powerful and weaker states, we can look back to 1944, when the IMF was created. When Western powers were discussing the Fund’s constitution at Bretton Woods, they sought to maintain control over its decision-making by claiming higher voting weights for themselves. Weak states, meanwhile, feared that policymaking under weighted voting rules would leave them vulnerable to future policy changes.

At the IMF's founding, Western powers sought to maintain control over its decision-making by claiming higher voting weights for themselves

However, if the IMF was to promote global financial stability effectively, the participation of weaker countries was key. To attract these countries, Western powers granted weak states institutional safeguards in the form of an exit clause. An adviser to the US State Department explicitly recognised this function of exit clauses:

'the damage which can be done to small nations is greatly minimized, since they can withdraw […] if they consider that their interests are being given short shrift. This circumstance, which is well known to the nations with larger voting influence, acts as a brake upon any inclination they might have to wield their voting power in an unrestrained manner.'

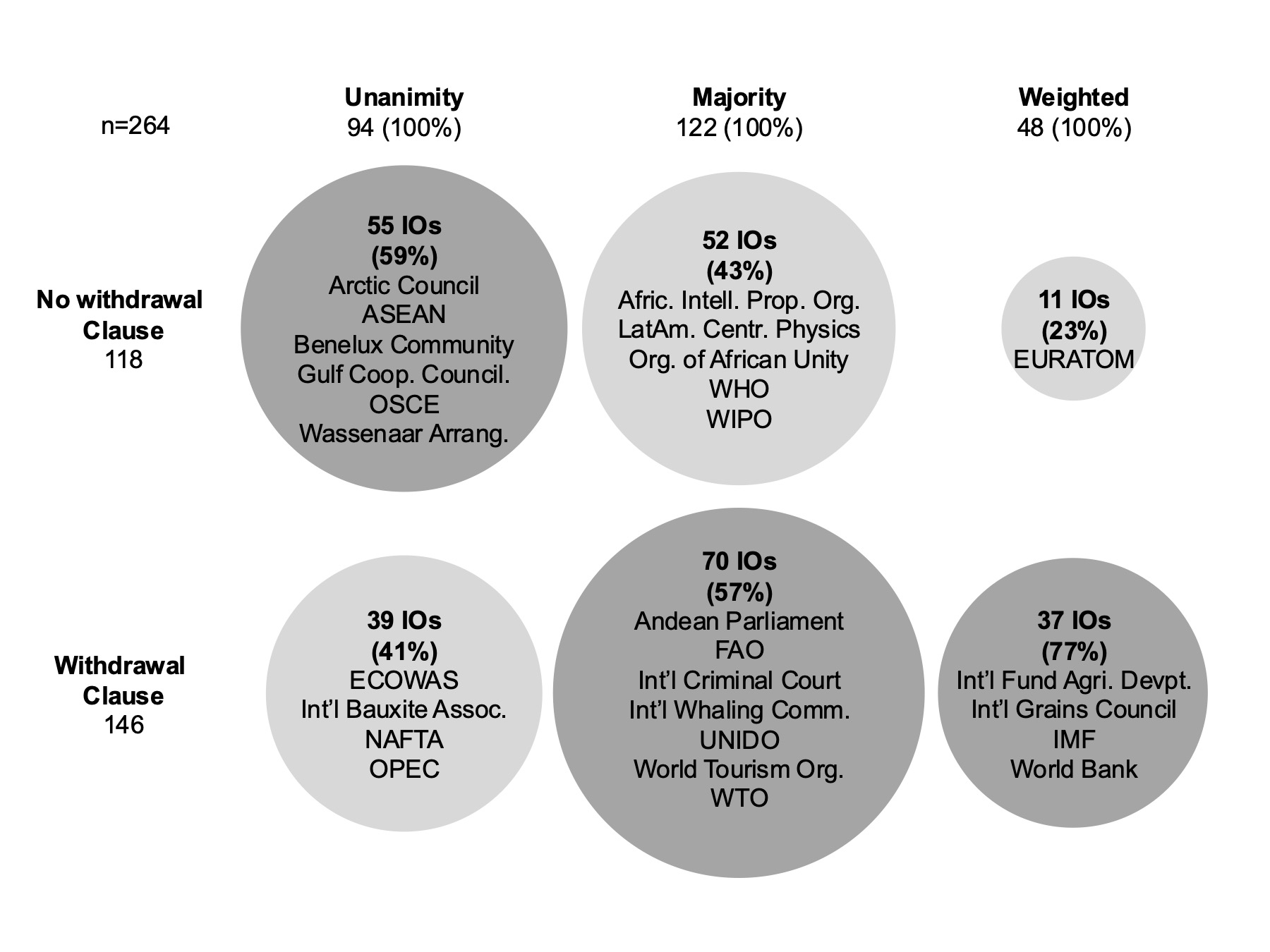

Our analysis of IO constitutional treaties reveals a correlation between power asymmetry among founding members and the inclusion of legal safeguards such as veto rights and exit clauses. The greater the power disparity, the more likely these safeguards were to be present. We also found support for our expectation that veto rights and exit clauses function as substitutes. If a treaty grants veto rights to member states, there is less need for exit clauses, and vice versa.

The graphic above shows that in IO constitutions which prescribe unanimous decision-making (i.e. have veto rights), exit clauses are less common (41%). When IOs take majority decisions following the one-state-one-vote principle, we observe more exit clauses (57%). And when votes are weighted, usually privileging the materially powerful, exit clauses are frequent (77%).

The institutional power equilibrium at the heart of postwar IOs has helped stabilise international cooperation. Rather than promoting gridlocks, veto rights have helped dissatisfied states remain IO members and promoted deliberation among their membership. Rather than leading member states to leave, exit clauses do not increase the likelihood of withdrawal.

But as power diffuses among member states, the institutional power equilibrium enshrined in IOs’ constitutions is upset. Western powers that have created most IOs, like the US, are declining. As they do, they lose control over ‘their’ institutions. Declining powers lose weighted voting shares, they are less able to organise majorities, and their special relationships with IO bureaucracies erode. Meanwhile, rising powers such as China and India gain leverage within IOs.

Reforms to international organisations – such as institutional privileges or special veto rights – could help maintain the participation of the most relevant states

As member states’ power and formal rules shift out of balance, major powers increasingly use veto rights and exit clauses. Unable to push through their preferred policies, declining powers abuse the institutional rules intended to ensure weaker states’ participation to extort or sabotage IOs. This, in turn, destabilises international cooperation.

IOs thus require reform to recalibrate the institutional power equilibrium. It remains important to provide safeguards for weaker members. But to ensure their continued participation, major powers require compensation for their loss of influence within IOs. One solution could be to grant institutional privileges, such as special veto rights or positions in an IO’s bureaucracy, to declining and to rising powers – both of which are essential for effective cooperation. At the same time, exit clauses could incorporate special penalties for powerful members. This would limit withdrawal – or at least cushion its effect on the IO.

Institutional reforms such as these promise to maintain the participation of the most relevant states. In a swiftly evolving geopolitical landscape, they would ensure IOs remain fora for constructive cooperation.