BBC general election night programmes since the 1950s have become increasingly frontloaded with discussion of projected results. Stuart Wilks-Heeg and Peter Andersen explain how this shift has developed in tandem with exit polling, and consider the implications for how election night politics unfolds

Late on 26 May 1955, a young David Butler, doyen of British electoral studies, sat beside Richard Dimbleby, the nation’s best-known broadcaster, in a BBC television studio. As the results of the general election were announced, Butler commented on the outcome in each constituency. In particular, he noted the swing – a measure of the movement of votes between the two main parties – invented by Butler himself.

Aided by doctoral students using slide-rules, he also offered periodic projections of the overall outcome. This, he explained, was possible because swing was fairly uniform throughout the country. After a single result, from Cheltenham, Butler projected the Conservatives would win 115 more seats than Labour. 'Is that what’s called being a psephologist?' asked Dimbleby.

Much has changed in broadcasting and political science since 1955, but aspects of BBC coverage from that era remain familiar. Butler’s last stint on election night was in 1979. Yet political scientists continue to play a central role in the broadcasts, notably Tony King from 1983–2005, and John Curtice since 1979. Richard Dimbleby hosted the programmes until 1964, with his son, David, anchoring from 1979–2017.

Superficial continuities aside, the content of BBC election night coverage has changed enormously since the 1950s. We recently published research on this subject in the journal Political Studies. Our article reveals that discussion of projected results now occupies a far greater share of the early parts of BBC election night coverage than in 1955. And this shift has consequences.

discussion of projected results now occupies a far greater share of the early parts of BBC election night coverage than in 1955

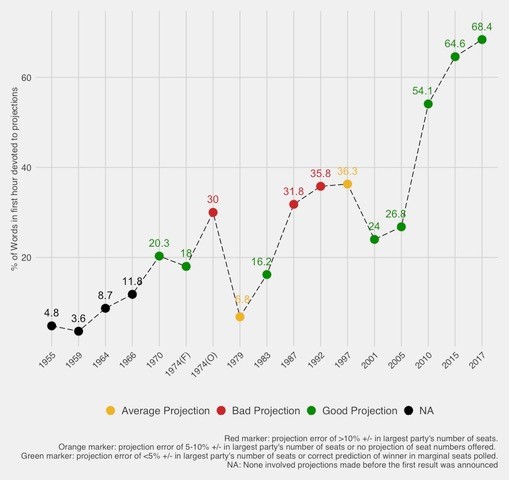

We generated and coded transcripts of BBC general election night broadcasts from 1955–2017. This allowed us to quantify how much attention was paid to different topics in the first hour of each broadcast. The figure below plots how much coverage concerned projected results.

David Butler’s rolling projections based on early declarations comprised 5% of the first hour of the 1955 broadcast. By contrast, presentation and reaction to the exit poll produced by John Curtice and his team accounted for 68% of the first hour of the 2017 programme.

The development of exit polling and the relative accuracy of exit polls in predicting the result helps explain the pattern. In 1970, the BBC piloted a proto-exit poll in the 'average' constituency of Gravesend. Although presented with a large dose of salt, it proved remarkably accurate.

By October 1974, advances in statistics, computing power and BBC ambition combined to create the first fully-fledged pre-results forecast. The BBC devoted almost a third of the first hour of the broadcast to it. But the projection proved highly inaccurate. The forecast suggested a sizeable Labour victory when, in fact, the party won a majority of just three seats.

As confidence in projections waxed and waned at subsequent elections, so did attention to them. In 1992, when the term ‘exit poll’ was first used, the projected result was again wide of the mark. Nonetheless, the BBC continued to frontload its broadcasts with discussion of exit polls, as the accuracy of projections improved in the 2000s and given expectations of close contests in the 2010s.

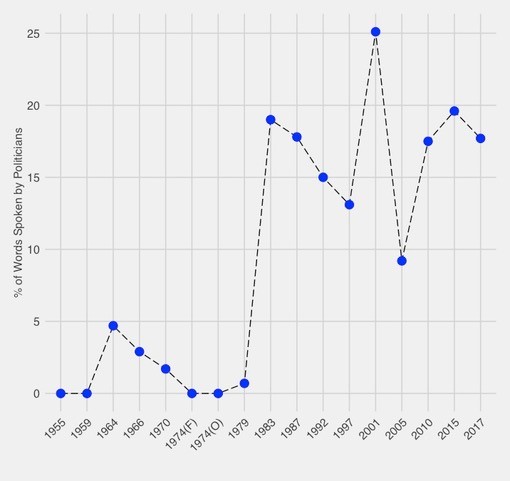

We also coded the transcripts to indicate which passages were spoken by different types of participants, such as broadcasters, academics and politicians. We found the greater attention given to projected results is associated with another clear trend.

From 1955–79, politicians barely featured in the early parts of election night broadcasts. But after 1983, the picture changed radically. Since 1983, around a fifth of the words spoken in the first hour have typically come from politicians’ mouths. In the main, the BBC is interviewing these politicians about projected results.

From 1955–79, politicians barely featured in the early parts of election night broadcasts. But after 1983, the picture changed radically

The airtime devoted to politicians responding to projected results also has political consequences. Presented with an exit poll, senior party representatives usually say it is too early to draw conclusions, but set out their competing ‘if this poll is correct…’ narratives anyway.

After all, between the exit poll and the actual results, there is plenty to play for. This may be to claim a mandate to govern or start a bid to replace a party leader in the face of likely defeat.

between the exit poll and the actual results, there is plenty to play for

In 1992, exit polls suggested Labour would be the largest party in a hung parliament – appearing to confirm pre-election polling. As the night progressed, Labour’s initial confidence in victory melted away, on live television, as the inevitability of a fourth successive election defeat became clear.

Banishing memories of that 1992 defeat is what drove leading figures in the subsequent creation of New Labour. The way election night 1992 unfolded clearly made the memory all the more painful.

In 2010, the exit poll’s projection of a hung parliament dramatically converted several Labour politicians, on live TV, to the cause of electoral reform. It was a desperate overture to the Liberal Democrats, who were set to hold the balance of power, and it didn’t work out.

The Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) enjoyed more success with its televised pitch to the Conservatives in 2017. With the exit poll projecting the Conservatives had lost their majority, the DUP set out its price for keeping them in office, live on the BBC. Two weeks later, the Conservatives and the DUP published a confidence and supply agreement.

Who needs smoke-filled rooms when you can start coalition talks from the comfort of a TV studio?