British politics has, traditionally, been divided along straightforward left-right lines. But Brexit disrupted this pattern, creating opportunities for a ‘European integration dimension’ to take hold, argues Connie Woollen. The deep rifts in public opinion, within parties and in Parliament, could dramatically reshape British electoral politics

Since the early twentieth century, British party politics has divided along simple left-right lines. Voters vote based on economic preference, and the two main parties fall neatly on that spectrum: Labour on the (centre) left, the Conservatives on the (centre) right.

Brexit, however, awoke the ‘sleeping giant’ that is Europe. It opened a window of opportunity for a new voting dimension to develop, if not take hold.

This new axis takes different names. Some call it the ‘cultural dimension’ or the ‘European integration dimension’. But it brings a whole new world of issues into play: transnationalism, immigration, multiculturalism, the list goes on…

Associated are the new Brexit-related identities: are you a ‘Remainer’ or a ‘Brexiter’? Such definitions cut across the traditional left-right economic dimension and party lines. The rising importance of these new European issues is dividing the parties, the public, and parliament.

Both Labour and the Conservatives have had a fraught relationship with Europe over the last few decades.

Euroscepticism among Conservative MPs rose from the early 1990s. Pressure from Eurosceptics led David Cameron to call the EU referendum which ended his – and, eventually, Theresa May’s – premierships. Grassroots Tories are strongly Eurosceptic: 69% of Conservative party members voted to leave the EU. Tory MPs in Parliament were, however, generally more remain-leaning.

Former Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn’s Eurosceptic reputation as Tony Benn’s protégé raised concerns about Labour’s pro-European views. It was also at odds with Labour's overtly pro-European grassroots and MPs. With Keir Starmer, a vocal Remainer, now Labour leader, views in the party appear mostly to have re-converged (at least on Europe).

Despite this friction, the two parties had broadly constituted coherent groups based on economic preferences. Then Brexit came along, and the parties could no longer ignore their difficult histories with Europe.

Brexit has been such a strain on the two major UK parties that in January 2019 the Conservative Government suffered the greatest defeat in House of Commons history. More than 100 of the party’s own backbench MPs rejected the government’s Brexit plans. Only a month later, multiple MPs from both parties defected to establish the (now defunct) Change UK, motivated in part by their former parties’ handling of Brexit.

Just days before the UK officially left the EU at the end of 2020, polling showed that public opinion stood just as split as it was in 2016, albeit with ‘remain’ coming out on top.

We have seen these Brexit-related divisions play themselves out at general and local elections since. The 2016 referendum vote heavily influenced the 2017 and 2019 ‘Brexit elections’.

In 2017, the economic left-right dimension continued to play a decisive role in voters’ minds. But factors that influenced Brexit attitudes – feelings towards transnationalism and the like – held more sway in this election than ever before.

A huge Tory win in the May 2021 local elections may be a sign that voters wanted to back the party that 'got Brexit done'

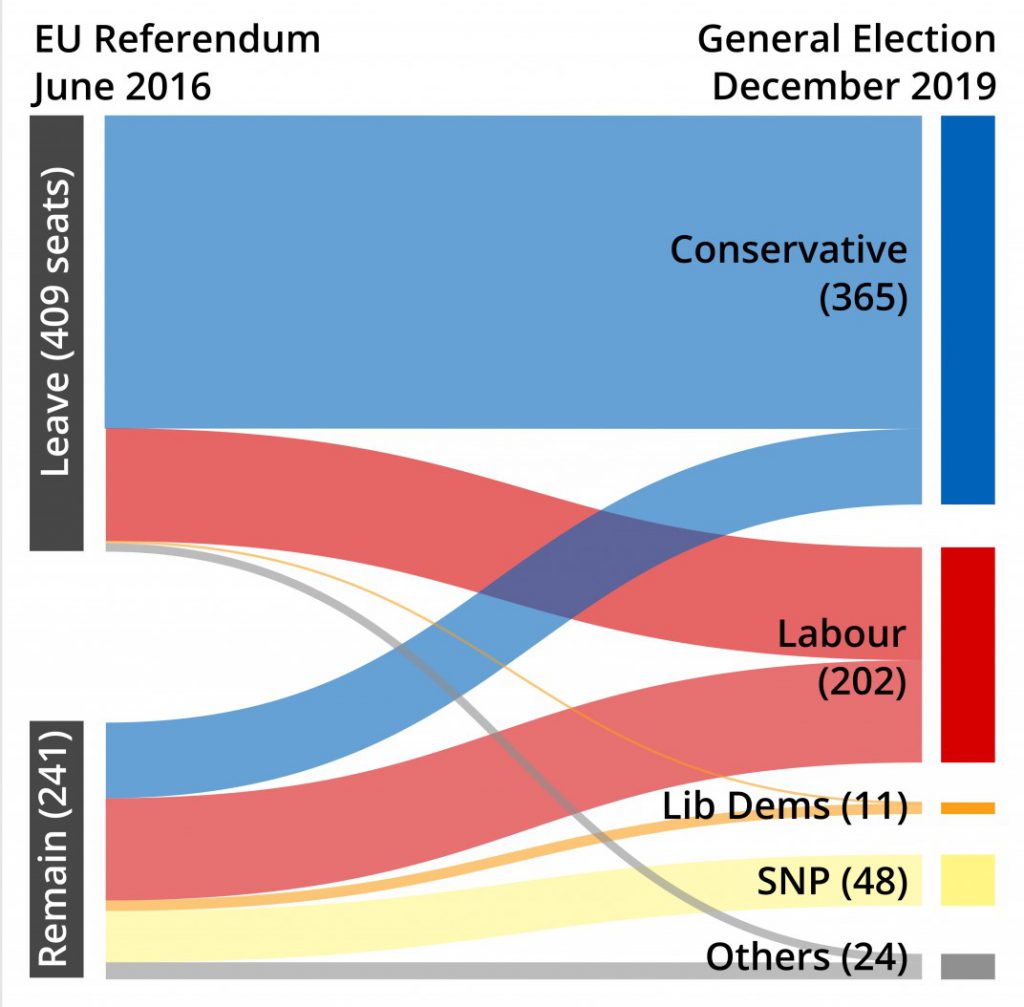

In 2019, Brexit was still central to both Labour and Conservative voters’ decisions. The graph below shows how the issue of Europe continues to cross party lines: while most leave voters backed the Tories, some voted Labour. Remain-voting constituencies were also split, but across an even greater number of parties.

Most recently, the Tories enjoyed huge wins in the May 2021 local elections. We can read this as a sign that voters wanted to back the party that ‘got Brexit done’.

My recent article in British Politics found similar patterns among MPs in Parliament as exist in the public at large. For the three years that followed the Brexit referendum, Labour and Conservative MPs were split along leave-remain lines, rather than by those traditional left-right economic preferences.

Contrary to assumptions that the Brexit division is binary, I found that many positions exist along the leave-remain spectrum. In fact, I identified six clear clusters of MPs falling between the two poles.

Brexit was too divisive across too many issues for MPs on either side to pull together as a homogenous group

That explains why a majority in line with the remain- and soft-Brexit-leaning Parliament never materialised: Brexit was too divisive across too many issues for MPs on either side of the EU debate to pull together as a homogenous group. It’s particularly significant that the two main parties with strong histories of party discipline couldn’t hold their own MPs together during such a critical period in British political history.

Brexit has moved away from the front and centre of political life. We see fewer headlines and the public and the media are experiencing Brexit fatigue. Many people don’t want reminding of the arguments and divisiveness of the years that followed the vote. And, of course, the Covid-19 pandemic has rightly taken a lot of airtime.

But Brexit still haunts the country. It continues to divide the parties, people and parliament, signalling that the European integration dimension is growing ever more salient.

Has Brexit become so definitive of Boris Johnson’s premiership that we’ll see a third Brexit election in 2024?

The increasing salience of this new voting dimension has the potential to continue its disruptive impact on party competition in Britain, at least when it comes to the issue of Europe. Only time will tell if Brexit causes lasting changes to British politics or whether we’re witnessing the end of the Brexit storm.

Will Kier Starmer’s radio silence on Brexit help brush Brexit under the carpet? Or will it become unignorable, as it did for Cameron, as Labour MPs and party members push for a stronger stance? Has Brexit become so definitive of Boris Johnson’s premiership that we’ll see a third Brexit election in 2024?

Many questions remain unanswered. What is clear, however, is that we are yet to return to business as normal in British politics – and it might be a while before we do.