Georgia is undergoing its most significant mass uprising since the 2003 Rose Revolution. The future of democracy in Georgia – and Georgia’s future in Europe – are at stake. John Chin and Anastasia Kim put this unrest in context by reviewing Georgia’s revolutionary history, and considering the ongoing challenges posed by Russian sharp power

Georgia has recently been rocked by ongoing anti-government protests, triggered by Prime Minister Irakli Kobakhidze’s announcement on 28 November that his Georgian Dream (GD) government – already dogged by allegations of fraud in October’s parliamentary elections – would suspend EU accession talks until 2028, and would refuse EU aid.

The popular mood shifted from resignation to fury. The following 16 days, per ACLED data, saw a record 100 demonstrations across the country.

This is not Georgia’s first revolutionary rodeo. Allegations of electoral fraud in the November 2003 parliamentary elections triggered the Rose Revolution against the decade-old post-communist dictatorship led by Eduard Shevardnadze.

The Rose Revolution’s success was aided by multiple factors, including a weak regime with a fragmented political elite and lame-duck president; the example of Serbia’s 2000 Bulldozer Revolution; extensive youth mobilisation galvanised by the chant Kmara (enough); widespread and disciplined nonviolent protest; independent television; a growing public desire to break with the communist past; and accidental US support.

Following allegations of electoral fraud in the November 2003 parliamentary elections, protestors marched into parliament with red roses

Within three weeks of the election, protestors marched into parliament carrying red roses. While the military remained quartered, Shevardnadze agreed to resign. His resignation paved the way for fair presidential elections in January 2004, which were won by Mikheil Saakashvili.

The Saakashvili government received support from the US – and drew Russian ire. In 2008, the Kremlin initiated a war with Georgia, backing the separatist territories of South Ossetia and Abkhazia that border Russia. One year earlier, in 2007, Saakashvili’s United National Movement (UNM) government had itself been the target of widespread opposition protests. These protests were violently repressed, but did succeed in prompting early presidential elections in 2008. The 'end of the Rose Revolution', however, did not arrive until 2012, with UNM’s electoral defeat to GD.

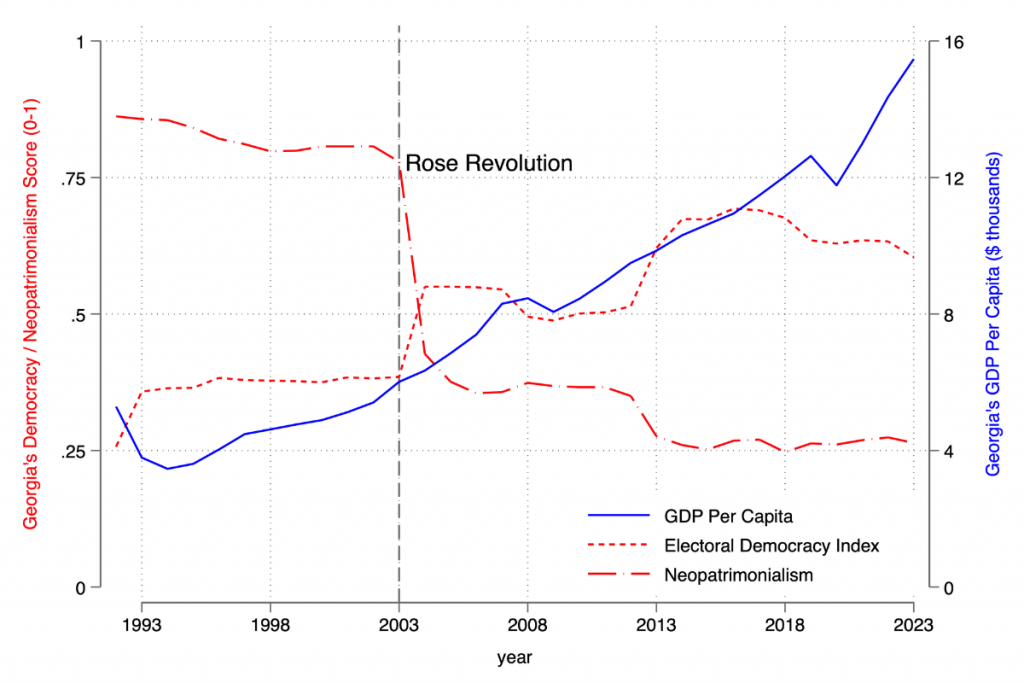

The causes of the current unrest are principally political, not economic. Average incomes in Georgia have been rising for years (see figure below). Two political sources of discontent stand out: democratic backsliding, and disagreement on how to navigate geopolitics between Russia and Europe as East-West Cold War tensions grow.

The Rose Revolution had a real but limited democratic dividend. Neopatrimonial rule declined steeply, per V-Dem data above. Yet democratic regression had begun in 2017, with GD curbing judicial independence, media freedom, and civil society opposition. Since 2012, anti-corruption reforms have stalled, and far-right mobilisation has increased. The opposition refused to recognise the legitimacy of elections in 2020 or 2024, both of which were won by GD. In October, Prime Minister Kobakhidze signed a Hungary-style anti-LGBTQ law.

Protestors also decry GD’s growing pro-Russia tendency. GD was created in 2012 by shadowy billionaire Bidzina Ivanishvili, who has longstanding ties with Russia. After Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Georgia didn’t sanction Moscow, and kept its distance from Kiev. In 2023 and early 2024, mass protests opposed a new 'foreign agents' law that signals rising Russian influence.

A constitutional crisis looms as pro-EU President Salome Zourabichvili insists she has not handed over legitimate power to GD-backed far-right politician Mikheil Kavelashvili. Prime Minister Kobakhidze threatened legal consequences if she stayed in office.

Like Romania, Georgia is a frontline state in Russia’s 'near abroad'. It is a target of Russian 'sharp power' but courted by the West. As Ghia Nhodia notes, 'without Western support, Georgia will be at the mercy of Russia'.

Georgia is a frontline state in Russia’s 'near abroad', a target of Russian 'sharp power' but courted by the West

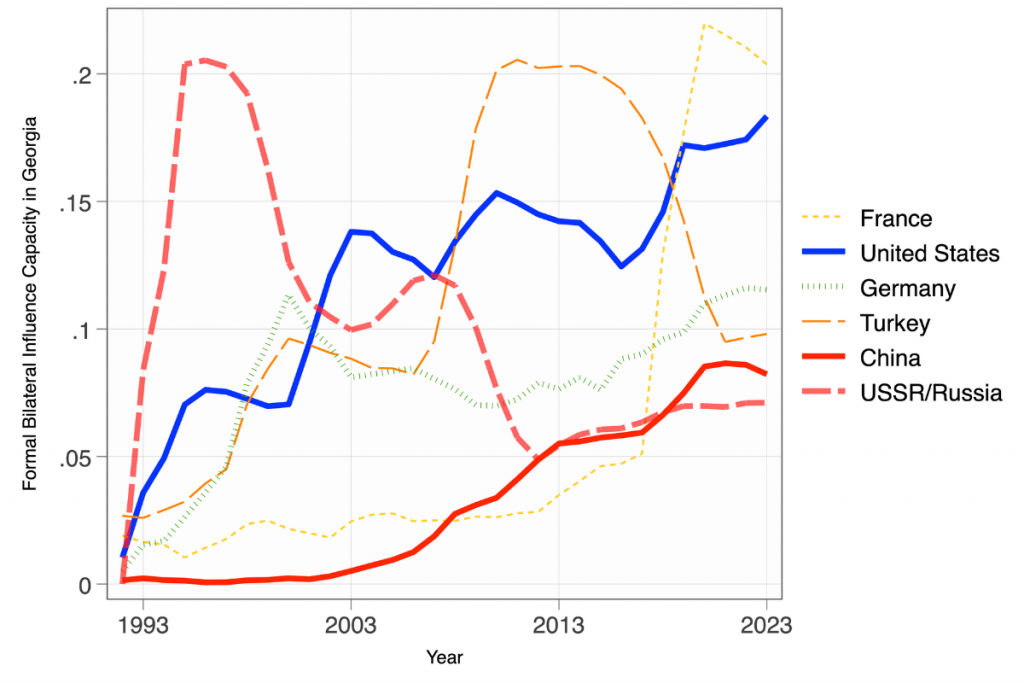

Georgia’s ties remain stronger with Europe than with Russia or China, though China’s influence has grown in recent years, as FBIC data shows. Indeed, in July 2023, the two countries signed a strategic partnership agreement. Russian influence in Georgia peaked in the mid-1990s, tanked after 2008, and has only partially recovered since 2012. US influence, on the other hand, continues to increase:

The goal of joining the EU and NATO is enshrined in article 78 of Georgia’s 2018 constitution. The EU and Georgia signed an association agreement in 2014 (entering into force in 2016), which included the Deep Comprehensive Free Trade Area that opened up the EU market for Georgian businesses and products. In December 2023, the EU officially granted Georgia candidate status. Recent polls suggest that large majorities of Georgians support membership of the EU and NATO, seeing Russian aggression and propaganda as the main threats to the country.

Yet since 2012, Georgia has also bolstered trade ties to Russia, China, and Iran. And since 2022, a record number of Russian-owned businesses have opened in Georgia. Critics worry that appeasing Russian interests risks turning Georgia into a de facto satellite like Belarus, especially if it calls on Russia to help quell domestic protests. But GD leaders insist they are not Putin’s stooges. Given the risks of confronting Russia, and pointing to Ukraine’s fate since the 2013–14 Euromaidan protests, they argue that they are simply being realistic. GD allies, meanwhile, accuse the West of trying to draw Georgia into the war in Ukraine.

The West is banking on protests and outside pressure to restore Georgia's path to European integration

The West is banking on protests and outside pressure to restore Georgia's path to European integration. After Kobakhidze’s announcement, the EU parliament called for parliamentary elections to be re-run under international supervision. The US announced suspension of its strategic partnership with Georgia that dates back to 2009. EU and US representatives have expressed their solidarity with the protesters. The OSCE condemned GD’s repression of recent protests, and the UK and US have imposed sanctions on high-level GD leaders, including the prime minister. On 27 December 2024, the US extended Executive Order 14024 sanctions to GD founder Bidzina Ivanishvili.

Georgian Dream adopted a sophisticated playbook to defeat recent pro-democracy protests. The protests are largely leaderless, which doesn’t bode well based on the outcomes of other recent protests. There have been some civilian regime defections, but the loyalty of security forces – the most important determinant of revolutionary success – has not wavered much so far.

Yet the protestors still have a critical ingredient for success – momentum – on their side. Whatever happens next, Georgia’s democracy, and its future in Europe, are at stake.