Legislative gender quotas are effecting change in Irish politics. However, argue Fiona Buckley and Mack Mariani, without strong party leadership and political will, advances in women’s political representation can only go so far. To maintain progress, party leaders must prioritise women’s recruitment, nomination, and financial support as well as retain incumbent women

The next general election in Ireland is due to take place by spring 2025. This election represents an important moment for women in Irish politics. It will be the country’s third under a legislative gender quota (LGQ) for candidate selection, and the first to require that political parties meet a 40% threshold for gender balance on their party tickets – up from 30% in 2016 and 2020.

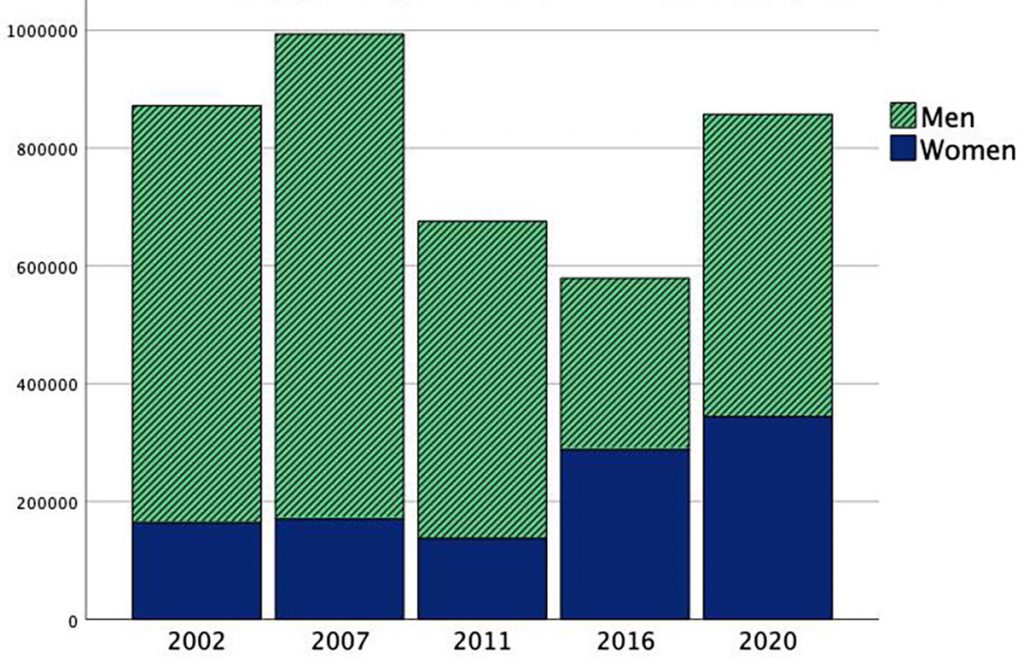

Ireland adopted LGQs in 2012 to address the severe under-representation of women in Irish politics. While Ireland was one of the earliest countries in Europe to grant suffrage to women and men on equal terms in 1922, by 2011, women’s representation in Dáil Éireann (lower house of parliament) stood at just 15%. However, since the law’s adoption, women’s candidacy has increased by 90%. The number of women elected to Dáil Éireann, meanwhile, has increased by 48%. Political parties have incentives to comply with the law through a financial mechanism. Under the Electoral Acts, non-complying parties lose 50% of their State funding.

The LGQ was first applied in 2016. After its introduction, the proportion of women candidates selected by political parties increased dramatically, from 18% in 2011 to 33% in 2016. The proportion of women elected also increased, from 15% to 22%.

In 2011, women's representation in Ireland's lower house of parliament stood at just 15%. After legislative gender quotas were applied in 2016, the figure increased to 22%

In the 2020 election, however, similar rates of progress were not observed. In that election, the percentage of women nominated by political parties remained largely unchanged (from 33% to 34%). The proportion of women elected, meanwhile, increased by just half a percentage point, to 22.5%.

Preparations are now underway for the next general election and with that comes questions such as: Will women’s representation stagnate again – or worse, experience a setback – despite the increased gender quota? Or will this election mark an important milestone toward gender equality in political representation?

The answers depend on party leaders making it a priority to recruit, nominate, financially support, and retain the women already there.

In relation to recruitment, experience matters. In 2020, for example, candidates with prior local experience were four times as likely to win election at the national level as candidates without such experience. The LGQ does not apply for local government elections. Nonetheless, it is important that political parties use the occasion of the forthcoming local elections in June to identify and recruit women for local office, and ensure that women can build their political résumés, strengthen community connections, and earn the trust of the electorate.

Doing so challenges the charge that gender quotas lead to the selection of inexperienced women. Those who make such arguments, however, often 'ignore the fact that where inexperience exists, it is a legacy of men’s domination of political office' and male incumbency.

It is important that party leaders nominate women who have a fair chance of winning. They can do this by giving women opportunities to contest constituencies where party candidates are well-positioned for success. Our research finds evidence that in 2016, some parties engaged in ‘sacrificial lamb’ strategies, nominating women with little experience or community support to run in constituencies where the party had little chance of electoral success.

In the 2016 election, some parties fielded women candidates as ‘sacrificial lambs’ in constituencies where they had little chance of success

To date, 15 incumbent members of parliament have announced that they will not contest the next general election. Thirteen of these members are men. These seat vacancies present opportunities to relevant political parties to run new candidates. A party that is seriously committed to increasing the number of women elected will seize this opportunity to run and support women candidates.

Though campaign finance is less important in Ireland due to the country’s highly localised and personalised political culture, it can make a difference. Indeed, our study of the 2016 general election found that well-funded candidates were more likely to win.

In 2016, political parties played an important role in helping to level the playing field for women candidates, assisting those who were less politically experienced and less able to raise funds on their own. Parties shifted their fundraising strategies between 2011 and 2016 in response to the gender quota, providing women with an increasing share of party expenditures, even as overall party spending was falling.

In 2020, parties increased financial support to candidates substantially, but almost all additional funding went to male candidates. Whether parties shift resources back towards women may depend on the strategic value party leaders see in the women nominated for the next general election.

A well-established principle in political science is that incumbency matters. Indeed, at the 2020 general election, just 15% of non-incumbent candidates won, compared with 75% of incumbent candidates.

Parties cannot assume that women incumbents, many of whom are relative newcomers to politics, are as safe as their longer-serving male counterparts

Parties should focus energies on retaining the women who have already proven themselves successful candidates. At the same time, women had less re-election success at the 2020 general election in comparison with men: 61% versus 79%. This suggests that parties cannot assume that women incumbents are as safe as their male counterparts. Many women incumbents are relative newcomers to the Dáil, whereas many male incumbents have served for many years and have a higher profile.

Of those elected in 2020, men had an average of 9.5 years of service in the Dáil, compared with 5.2 years of service on average for women. Women were also more likely to be serving in their first term, with 44% of women first-timers versus just 27% of men. Furthermore, our research shows that women are less likely than men to have such well-established networks, which can be crucial for fundraising. Party leadership should thus do more to ensure that newly elected women, as well as female newcomers, receive strong financial and personnel support on the campaign trail.

A record number of 174 Dáil seats will be filled at the next general election – an increase of fourteen seats on the current Dáil. Together with the above-mentioned seat vacancies, this presents an important opportunity for political parties and party leaders in Ireland to fully embrace the LGQ. If they don’t, they risk advances made stagnating further, or worse, subject to reversal.