Feminist and justice-oriented design frameworks offer pathways to democratic transformations. Jesi Carson draws on her experience as a design practitioner and researcher in collaborative projects, including Participedia and the Global Classroom for Democracy Innovation, to explore the transformative potential of design thinking

We are in a constant dance of transformation as we adapt in relation to the people, beings and world around us. Large-scale societal change in a world in crisis requires radical, democratic transformations of our individual and collective identities. It can be hard to see, practically, how these transformations are possible when faced with wicked problems.

Design thinking offers a way forward.

Engaging in design justice, a critical iteration of design thinking involving collaborative, community-engaged, equity-centred work, can be transformative on many levels. Transformations begin with the individuals involved and echo outward, potentially leading to larger-scale change.

In The Politics of Becoming, Hans Asenbaum describes this phenomenon as the creation of a 'democratic microverse', where small-scale shifts can transform larger systems, setting the stage for more democratic futures. He reflects on identity politics in these spaces, and how identities are malleable and multifaceted as 'identity assemblages' of our values, beliefs and dreams.

Transformation, like design, is cyclical and iterative. As we transform our identities, we transform our worlds. In the process of transforming our worlds, we too are transformed. I explore this potentiality in my work.

As we transform our identities, we transform our worlds. In the process of transforming our worlds, we too are transformed

In the Global Classroom for Democracy Innovation, we engage identity politics by inviting students to become activists. In our programmes, students collaborate in teams over five weeks to address real-world design challenges posed by civil society and grassroots activist community partners. Through course evaluations, summary reports, and interviews, we know most participants do not self-identify as activists prior to joining. But through the learning experience they see the potential for collaborative action at the community level. Thus, they can envisage how they might manifest democratic action in their own lives and communities. The difficult-to-imagine scenario of making change in the world suddenly becomes possible, less intimidating, and even fun! This shift in perspective paves the way for democratic transformations.

Ezio Manzini suggests the defining characteristic of 'emergent design' is the value it places on processes and methods, rather than end products. Similarly, the transformative potential of the Global Classroom lies in the journey, not the destination.

The Global Classroom aims to overcome the blind spots and power dynamics typical of higher education institutions

We use empathy-based activities, taking time and making space for participants to bring their whole, multiple selves to the experience. Early on in the process, we visually map individual and shared matters of concern. In doing so, we are celebrating our multifaceted identities, embracing a diversity of views and ideas, and creating the conditions for collective intelligence to emerge. It is precisely this shift from individuality to the collectivity created in the democratic microverse, while acknowledging the diversity and wisdom of the individuals within these spaces, that seems key to transformation on a larger scale.

Rua M. Williams’ 'fractal mechanics' and Adrienne Marie Brown’s Emergent Strategy describe our very existence as fractal, pattern-based. When society is built on patterns of inequity, the logical result is inequitable existence. Working within institutions and organisations dedicated to social change and justice, it is not uncommon to observe how the structures of these spaces can unintentionally perpetuate the status quo. In the Global Classroom, we aim to address some of the 'borders' — blind spots and power dynamics — typical of higher education institutions. We might make space, for example, for diverse knowledges of participants from the Global South. Supporting individuals doing justice work requires justice frameworks at the organisational or institutional level.

Participedia is a global research community exploring democratic innovations. Working with Participedia has taught me that inclusive, justice-oriented work requires inclusive frameworks. Applying feminist frameworks through participatory design led to better alignment of Participedia’s values to its practices. It also shaped the team’s collective identity.

Founded in 2009, Participedia has grown into a large, multidisciplinary network of scholars, practitioners, activists and students. The crowdsourcing platform Participedia.net was envisaged as a hub and shared database for decentralised, global research on democracy. I was invited to join Participedia’s Design Technology team in 2015 to evaluate and modernise the platform.

Participedia is not only a project about participatory democracy; it is participatory and inclusive in its collective identity

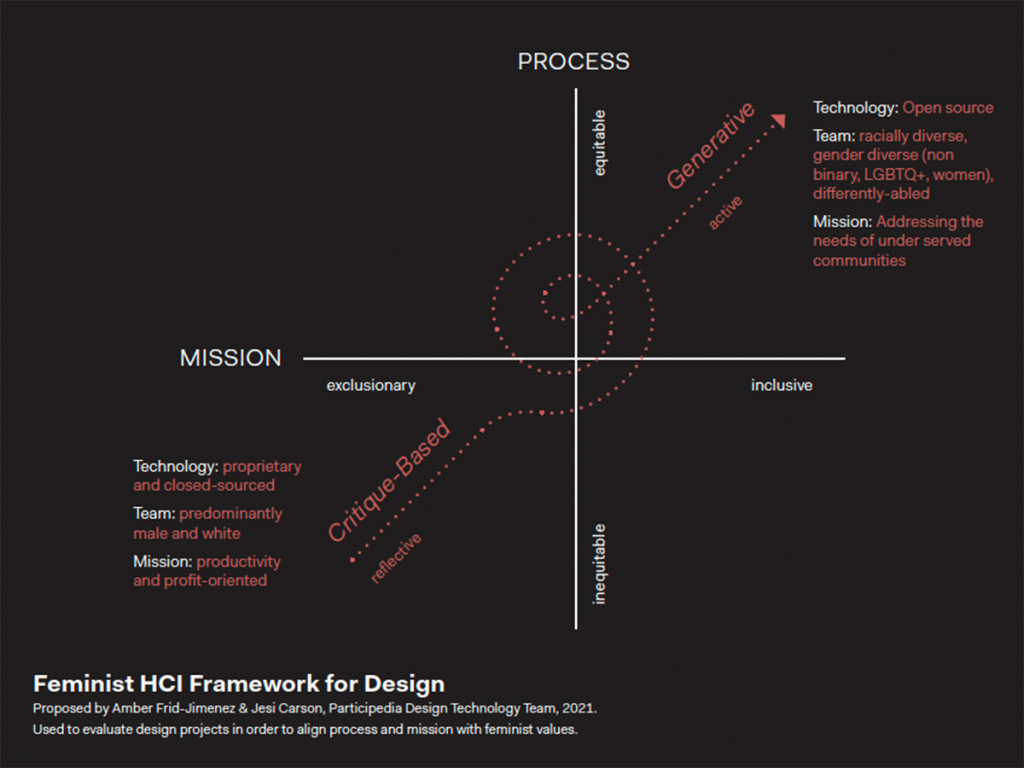

Drawing on feminist human computer interaction (HCI), we identified opportunities for Participedia to actively demonstrate its commitment to democratic values. We wanted it to shift from critique-based to 'generative' technology for social good, as the diagram below illustrates. Applying this theory in practice, we engaged the Participedia community in a co-design process and transitioned the platform to an open-source technology approach with a focus on student mentorship.

Making generative changes at the organisational level has grown Participedia’s potential for impact. For example, high-profile partnerships and experiments have emerged as a result of Participedia’s open source codebase on Github. We also observed shifts in understanding and awareness among Participedia team members. Not only is Participedia a project about participatory democracy; the project is participatory and inclusive in its collective identity.

Participating in design justice projects can be transformative on many levels, including transforming our personal identities. Transformation on a small scale can influence larger-scale democratic transformations. Conditions for these kinds of transformations include creating inclusive, safe spaces where our whole, multiple selves are invited.

How might we continue to create the conditions for transformation in our pluriverse of contexts, in a world in crisis? I see design as a bridge between the many ways change agents can tap into the collective imagination. Leaning into engagement methods that foster collectivity and embrace our diverse identities can help us imagine and co-create alternative democratic futures.