Jochem Vanagt and Markus Kollberg show that coalition governments bring voters of different parties closer together only if people believe those coalitions are doing a good job. When voters think coalitions are performing badly, partisan hostility remains high. Their insights have significant implications for efforts to reduce affective polarisation

Coalition governments often attract praise for bridging divides in multi-party systems. The thinking goes that when two or more parties govern together, their supporters create a shared ‘coalition identity’ that dampens animosity between them. This stands in contrast with two-party systems, which can lock politicians into winner-takes-all competition, and intensify partisan hostility.

In countries like Sweden, Denmark, and Belgium, coalition governments have been the norm for decades. Nevertheless, partisan hostility here can be as strong as, or even stronger, than in two-party systems such as the United States. So why do these ‘consensual’ democracies still struggle with partisan conflict?

Our research in EJPR tackles this puzzle. Drawing on data from multiple Western democracies, we argue that simply being in a coalition does not necessarily bring voters closer. Instead, voters have to see the coalition as performing well. If people think their government is failing, any reduction in affective polarisation that comes from governing together vanishes.

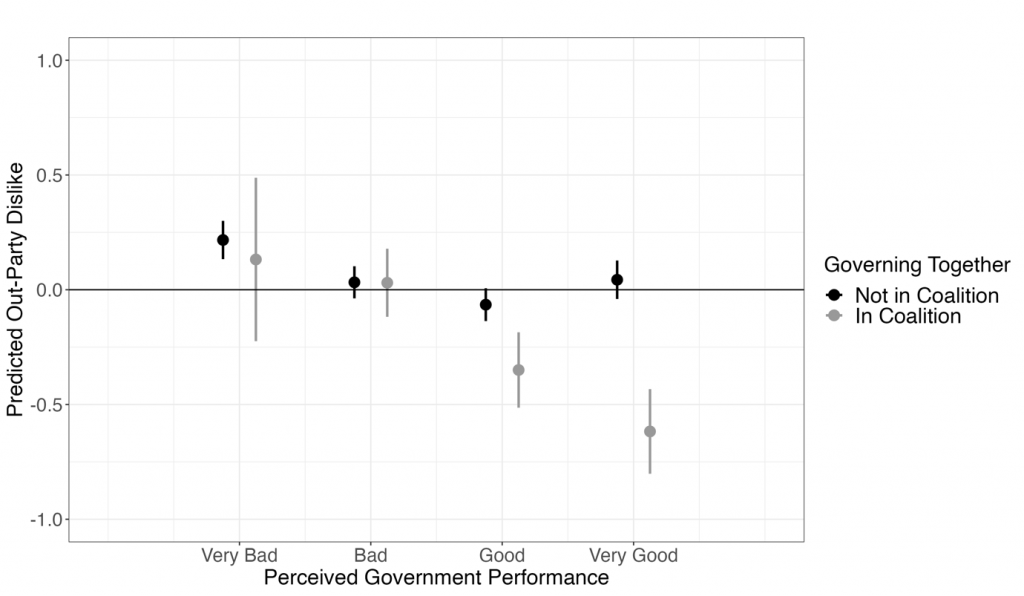

The graph below illustrates this dynamic. It shows how voters’ dislike of other parties changes depending on whether their own party is in a coalition and whether voters consider that government is performing well or poorly.

Among voters who believe the government is doing very well, there is a notable drop in hostile feelings toward other coalition parties. By contrast, if voters think the coalition is performing badly, there is no decrease in dislike. In other words, the positive effect of governing together is present only among voters satisfied with that government’s performance.

The positive effect of governing together is present only among voters satisfied with that government’s performance

We also looked at why a 'successful' coalition might help reduce out-party hostility. One explanation we find is that when voters perceive a government is doing well, they begin to see coalition partners as more ideologically similar. This decrease in ideological distance, in turn, likely leads to the aforementioned decrease in dislike.

These findings hold insights for combatting affective polarisation, wherein party supporters express negative feelings toward one another. Many commentators are optimistic that structural reforms, such as introducing proportional representation to encourage coalition-building, might reduce affective polarisation. But our results caution against expecting too much from such reforms alone.

If voters perceive a coalition as dysfunctional, their partisan biases remain

Even if electoral rules push parties into governing coalitions, such alliances must work in the eyes of the public. If voters perceive a coalition as dysfunctional, their partisan biases remain. Indeed, hostility can remain just as strong as if there had never been a coalition at all. By contrast, when coalition parties convince voters that they are governing effectively, affective polarisation cools down.

Those looking to reduce partisan hostility can take an important lesson from our research: successful cooperation matters more than cooperation alone. It is not enough to form a multi-party government on paper; the public must see tangible achievements and a clear shared purpose.

There is an added challenge for coalitions that include ideologically distant or radical challenger parties. Our research offers preliminary evidence that even if voters think a broad alliance is delivering results, the potential for reducing animosity is more limited than when a coalition is less ideologically diverse.

Successful cooperation matters more than cooperation alone. The public must see a clear shared purpose

Ultimately, coalition politics can lower affective polarisation, but only under the right conditions. In an era marked by fragmentation and political distrust, voters need proof that parties can indeed collaborate. Without it, partisan animosity remains entrenched.

Institutional reforms alone won’t solve the problem. Instead, by focusing on how to govern effectively, leaders can create the shared sense of purpose needed to bring voters closer together, and depolarise society.