Austrian parties have finally formed a new government – on their third bargaining attempt. The failure of the previous rounds drew media criticism of timewasting. But Matthew E Bergman and Wolfgang C Müller argue that time spent bargaining is in fact an investment in future government policy productivity

Single-party majorities are rare in European politics. Parties must therefore negotiate before entering office to secure a majority for government survival and the successful passing of legislation. Forming a coalition government is the goal. Yet, some bargains take considerable time to strike. Many dismiss drawn-out negotiations as costly ‘timewasting’. Protracted negotiations may even result in uncertainty in financial markets, which are often forced to wait for signals of government policy.

In our research with Hanna Bäck, we take a different perspective. During the negotiation stage, parties become aware of the issues on which others are willing to compromise, and those which constitute red lines. Before and during an election, parties’ true positions are unknown. True, parties may take positions in their manifestos and during the campaign, but afterwards citizens know that parties must compromise. Parties make a variety of proposals public. Partisans can react and signal to their party leader whether they are willing to accept any such compromise.

Detailed negotiations with potential coalition partners readies parties to govern, because they have already eliminated points on which no party is willing to compromise

A longer bargaining period can also alleviate the difficulties of governing with an ideologically distant partner. Negotiations might make parties realise how detailed their agreement needs to be. Parties then can take office ready to govern, because they have already eliminated non-agreeable policy solutions.

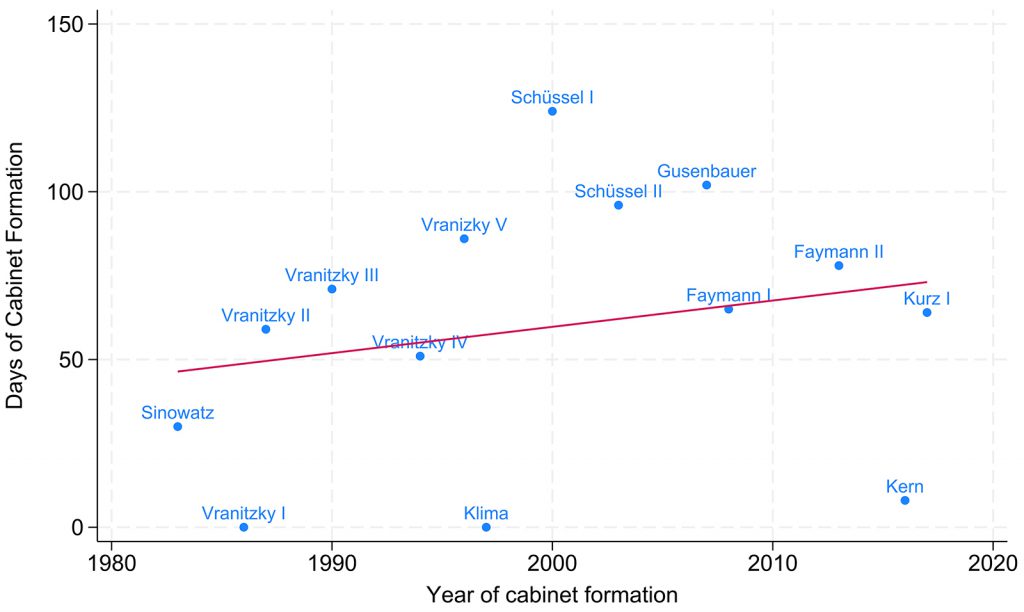

Since 1983 no party has won a majority in Austrian elections. The graph below indicates how long bargaining has taken for each subsequent government. A trend line indicates that bargaining has taken longer since the 1980s. Two aspects of Austrian politics explain this trend: fragmentation and the rise of more extreme parties.

As more extreme parties gained in popularity, this may have forced mainstream parties into protracted negotiations – either to find common ground with the new parties or because the more competitive environment makes compromise between the traditional parties more difficult.

The current election exemplifies fragmentation and extremity. Austria elected a new parliament on 29 September 2024. The outgoing government of the conservative ÖVP and Greens, installed in 2019 as the first of its kind, had led the country through the crises of inflation and Covid, becoming quite unpopular in the process.

The right-wing FPÖ was the main beneficiary of this, having led opposition to Austria's Covid restrictions. The FPÖ gained 26 seats in the election, finishing with 57 of the 183 seats, and 28.8% of the vote.

| Party | Status at election | Seat change (total) | % vote change (total) |

|---|---|---|---|

| FPÖ (Freedom Party) | Opposition | +26 (57) | +12.7% (28.8%) |

| ÖVP (People’s Party) | Incumbent | -20 (51) | -11.2% (26.3%) |

| SPÖ (Social Democrats) | Opposition | +1 (41) | -0.1% (21.1%) |

| NEOS (Liberals) | Opposition | +3 (18) | +1.0% (9.1%) |

| Die Grünen (Greens) | Incumbent | -10 (16) | -5.7% (8.2%) |

Given these results, what possible coalitions were there? Mathematically, the FPÖ and ÖVP could form a right-of-centre majority; the ÖVP and SPÖ a one-seat centrist majority. The more likely outcome, however, would include another of the centrist parties, to ensure a stable legislative majority. Each bargaining possibility has occurred, and each has informed future government policy, enabling the incoming government to focus on policy-making instead of internal deliberations.

An ÖVP-SPÖ-NEOS formation attempt came first, but was overshadowed by uncertainty about the huge budgetary gap any new government would face, which would require tough austerity measures. The parties agreed on many issues, and overcame narrow intra-party differences. But the budgetary problem remained. After two months, NEOS left the table, accusing the other parties of fearing reforms. The ÖVP followed suit.

During the bargaining process, each potential coalition permutation has occurred, and each has informed future government policy

FPÖ and ÖVP made the next attempt. Within a week, the two agreed on an austerity-measures package. These were reported to EU institutions, which agreed that they met Maastricht criteria. This attempt had multiple advantages. The parties were closer economically, the budgetary gap was known from the beginning, and austerity measures had already been worked out. Parties agreed on many issues, and narrowed their positional gaps on others. There were some key polices and portfolio allocations, however, on which they could not agree. After more than a month, the FPÖ-ÖVP formation attempt collapsed amid mutual recrimination.

To avoid early elections, the ÖVP and SPÖ resumed talks. Within days, they invited NEOS to join. The parties were quick to commit to the austerity package agreed by EU institutions, and on the parameters of the next two budgets. The SPÖ capitalised on the ÖVP’s earlier concession towards FPÖ of a special tax for banks. Within little more than a week, the three-party bargaining resulted in a 210-page coalition agreement, and consent on design and allocation of portfolios.

When asked whether politicians felt the first bargaining round could have produced the three-party agreement, representatives from all parties said no. They stressed that all kinds of informational gains were made during the bargaining process: budget issues, for one. Perhaps most importantly, however, politicians felt the various bargaining rounds had clarified possible futures and made choices between them much easier.

Politicians stressed that they had made many informational gains during the bargaining process, and possible futures were now clearer

Austria's most recent rounds of coalition bargaining were the longest on record. But this isn’t necessarily a bad thing. Each day and each new round of bargaining provides valuable information to the government that does eventually form.

Instead of focusing on the failures of such bargaining, we suggest that government parties make informational gains on their partners’ policy positions and objective constraints. Since the parties are now aware of potential bargaining ranges, the incoming government should be able to get to work quickly in addressing the nation’s problems.