International observers generally praise the rise in female politicians in autocracies, but the inclusion of women in politics can also be a means by which autocrats polish their image without real reform. Janina Beiser-McGrath and Eda Keremoğlu caution that authoritarian states do not necessarily become more democratic, even if women gain real power in their cabinets

Women have been gaining increasing access to centres of political power in autocracies. International observers welcome this as a crucial step toward political equality. However, scholars warn that women’s inclusion can serve merely to consolidate authoritarian rule.

Despite women's increasing representation in autocratic cabinets, they still have only limited access to the most powerful portfolios. Autocratic leaders also tend to treat female cabinet members differently. Our research shows that, on average, autocrats are less likely to perceive women as threatening opponents. This changes, however, when women’s threat potential increases, as in situations where they gain access to important cabinet positions.

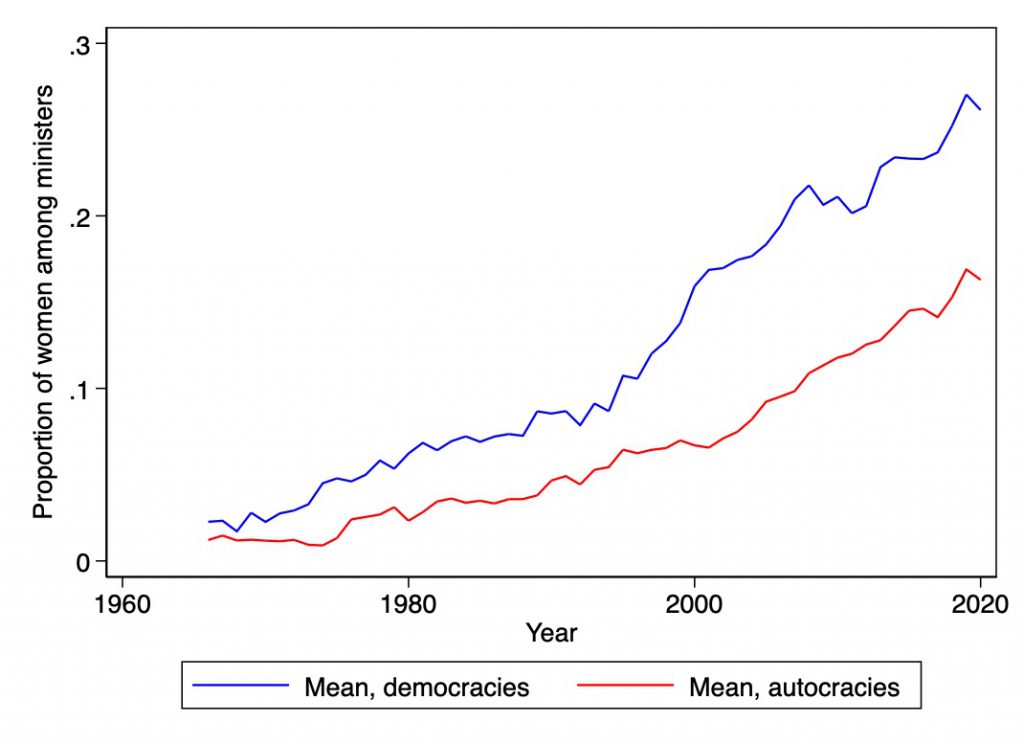

Women’s access to power is increasing, though it is still far from reaching parity with men. Democracies are at the forefront of this trend, but non-democratic states, too, have seen increases in women’s inclusion. Data on cabinet members around the world in the graph below shows the average proportion of women among ministers for democracies and autocracies since 1966. In both regime types, women’s access to cabinets has increased sharply over time. While the average proportion of female ministers is higher in democracies, non-democratic states mirror this trend closely.

In 2020, nearly a third of cabinets in autocratic countries comprised at least 20% women

In 2020, it was uncommon among democracies to see no women in ministerial posts. Indeed, Papua New Guinea is the only democratic exception worldwide. Eight autocracies, including China, Burma, Iran and Saudi Arabia, lacked any female ministers. However, 32% of autocratic cabinets comprise at least 20% women ministers.

While gaps in social, economic, and political equality persist, international organisations have highlighted the progress made over recent decades. The growing inclusion of women has generally attracted praise. Yet at the same time, gender and autocracy scholars have sounded the alarm about autocrats’ strategic use of gender equality reforms.

By appointing women to their cabinets, undemocratic leaders can burnish their reputation without the bother of introducing meaningful democratic reforms

With genderwashing strategies, undemocratic leaders can burnish their reputation without the bother of introducing meaningful democratic reforms. Studies show that the inclusion of women in politics can cloud Western judgements about how authoritarian some states are. In certain cases, the push for women’s inclusion only entrenches ruling parties’ power, by promoting regime-loyal women and marginalising the opposition. So, while women’s presence in positions of power in non-democratic states is on the rise, we still lack insight into what roles these women play, and whether they hold similar influence to men in those states.

Autocratic regimes strategically exploit women’s political empowerment to their advantage. It is therefore crucial to understand how much influence women in political offices truly wield.

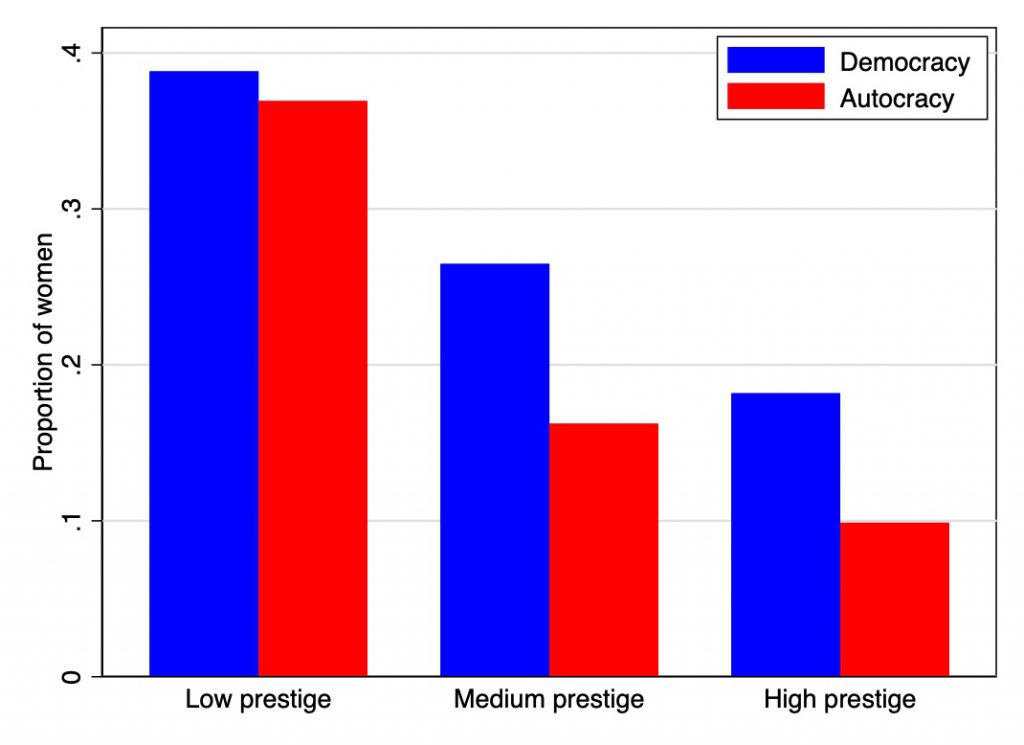

The graph below shows which types of portfolios women tend to hold in autocracies and democracies. The data distinguishes three different types of portfolios, depending on prestige and influence: high-prestige portfolios such as foreign, interior and finance, medium-prestige portfolios such as justice and education, and low-prestige portfolios such as women or tourism.

Regardless of regime type, women have most access to low-prestige portfolios. In democracies and autocracies, respectively, 39% and 37% of ministers in those portfolios are women. Women’s access to medium- and high-prestige portfolios is lower across regime types, but especially in autocracies. In autocracies, 16% of ministers in medium-prestige portfolios and 10% of ministers in high-prestige portfolios are women. In democracies, on the other hand, there are 26% women in medium- and 18% in high-prestige portfolios. Women are thus most underrepresented in the higher echelons of power, especially in autocracies.

Finally, women’s status in authoritarian regimes is also revealed through their inclusion (or not) in an autocrat’s trusted inner circle, and in how far they are perceived as a potential threat. Fearing coups, autocratic leaders are notoriously suspicious of elites in government. Some engage in frequent cabinet purges and reshuffles to prevent the formation of uncontrollable networks.

Once women in autocracies gain access to powerful cabinet positions, they are no longer less likely than their male counterparts to be purged

We investigated whether autocrats perceive female cabinet members as less threatening than their male peers and whether they would therefore be less likely to target women in cabinet purges. Our analysis of data on individual cabinet members in autocracies around the world finds that, on average, women are indeed less likely to be purged from cabinet than men. But there is a caveat: this is not a general effect that holds irrespective of women’s position. Rather, we find that once women gain access to powerful cabinet positions, their safety in cabinet also diminishes and they are no longer less likely to be purged from cabinet than their male counterparts. Women can be powerful players in autocratic inner circles and advance to prestigious positions – until autocrats recognise them as potential defectors and a threat to their position.

Women will likely play more prominent roles in autocratic politics. Yet we need a better understanding of the conditions under which women attain high political offices, the paths and obstacles to female leadership, and women’s policy influence. These insights could help international actors to better promote gender equality and democracy.