Recent elections in several countries have produced inconclusive outcomes. This has resulted in extended periods of bargaining between parties to determine the next government. Matthew E Bergman, Hanna Bäck, and Wolfgang C Müller argue that contrary to conventional wisdom, long bargaining periods might actually be a constructive investment in future productivity

On 22 November 2023, the Netherlands held a general election. When no clear majority emerged, the media emphasised the great difficulty Dutch parties now face in negotiating a coalition. Reuters reported 'No agreement in sight', and the Guardian that talks had begun 'but [are] far from forming Dutch Government'.

The Dutch are not alone in experiencing extended government formation processes. As party systems become more fragmented, governments around Europe are taking longer to form. In Sweden, a country where government formation has typically been a swift process, the 2018 election resulted in a drawn-out formation process lasting four months.

Academic literature in coalition studies typically takes a negative view of extended bargaining periods between elections and government formation. Generally, it holds that such long negotiation processes are simply 'wasting time'.

Much existing academic literature holds that extended bargaining periods between elections and government formation are merely wasting time

It sounds plausible. Without knowing the future direction of the country and its likely policies, companies do not know whether to invest. Consumers might not know whether it would be best to purchase, say, a house or car, and whether to do so now or later. There are also international implications. States typically refrain from making commitments to other states until a new government has taken office. In general, then, coalition bargaining time generates uncertainty.

Research until now has considered coalition governments to be ‘weaker’ than single-party governments in that they are less likely than single-party governments to ‘make a difference’ in policy innovations. The public shares this belief. Moreover, there is good reason for expecting such ‘weakness’. Coalitions need multiple political actors to agree to a reform in order for it to be enacted, which may be difficult when parties have diverging policy preferences.

In contrast, we argue that coalition negotiations are not wasted time, but instead lead to more productive coalition governments. We argue, too, that not all coalition governments are ‘weak’ in the above sense. For example, a written coalition agreement can serve to strengthen the policy-making ability of coalition governments. We develop an argument as to why bargaining over a policy programme during government formation promises productivity gains over bargaining when the government is in office. And we offer evidence that a public coalition agreement could narrow the policy-productivity gap between coalition and single-party governments.

We argue that bargaining over a policy programme during government formation promises productivity gains over bargaining when the government is in office

We then make the case that the bargaining process itself can lead to productivity, even without a conclusive coalition agreement. In that process, parties learn about the policy constraints of their potential partners and where policy agreement with other parties is feasible. During the negotiating time, press releases, media reports, or leaked documents might make their way to the public or interest groups. Parties thus know beforehand which topics might be too controversial to pursue during their term in office.

Longer bargaining time is also associated with longer coalition agreements. With more policies agreed upon beforehand, parties can focus more time in office on enacting policy.

In order to evaluate these arguments, we created a dataset that measures how many new policies a government has enacted. To do this, we turned first to the Economist Intelligence Unit. EIU data documents any major changes to the political or economic environment for businesses interested in investing in a country. We also analysed data from the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, which documents countries’ comparative policies on a variety of topics including health, pensions, employment policy, and taxation.

For ten Western European countries, from 1978–2017, we noted any change to social policy, taxation policy, regulatory policy, or labour policy that occurred as a result of a coalition government’s action. This resulted in a dataset covering over 5,000 reform measures.

To evaluate our arguments, we analysed whether governments with an agreement were more productive, in terms of implementing more reform measures, than those that did not have such an agreement. We also aimed to discover whether those with longer bargaining time were more productive than those with shorter bargaining time. The Representative Democracy Data Archive provided us with this data on the bargaining environment.

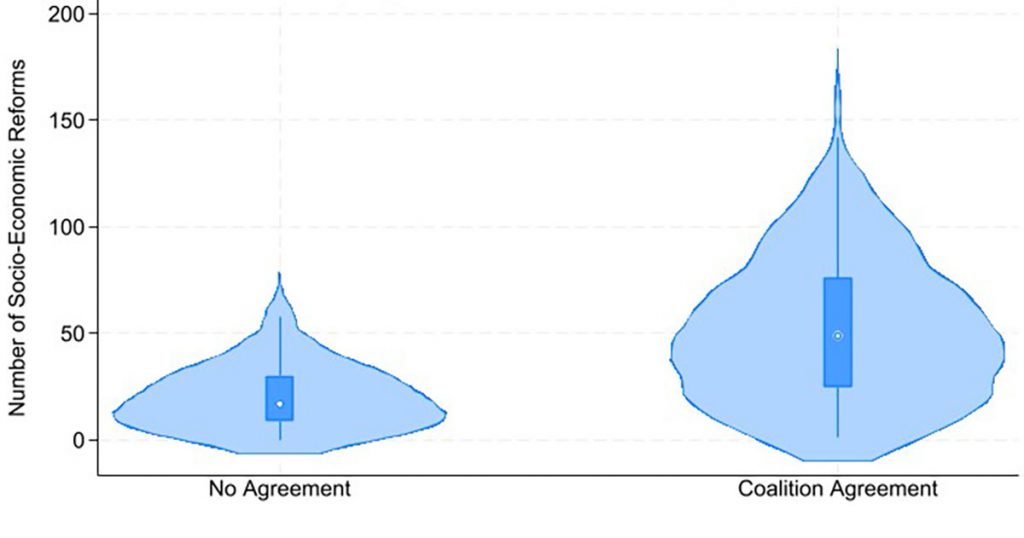

The figure above plots the number of reforms by 153 coalition governments separated by whether the government had a coalition agreement or not. The violin plot demonstrates the frequency of number of reforms. We can see that the bulk of governments without an agreement make fewer than 25 reforms. Those with an agreement, on the other hand, tend to make more than 40 reforms. We also demonstrate that this distinction holds when controlling for a number of important features, such as those related to the economic situation a government faces or how long it was in office.

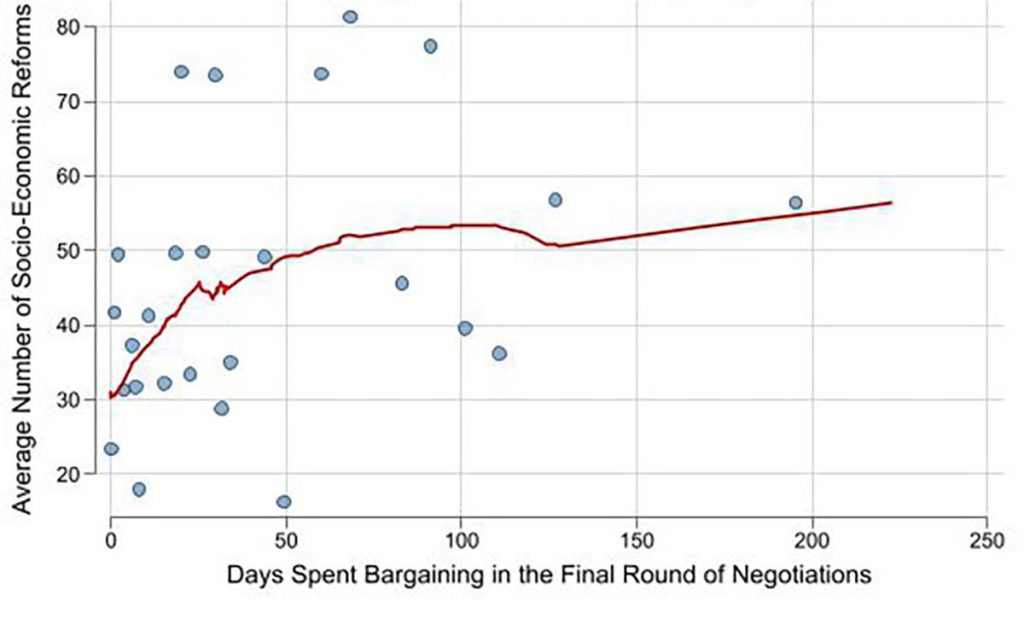

Our research found that as the number of bargaining days increases, expected government productivity also increases

This next figure looks at how many reforms were made by coalition governments based on how many days it took for the government to form. For ease of interpretation, the figure also shows a Lowess trendline and bins our data into 25 points. As the number of bargaining days increases, the expected government productivity also increases. That said, productivity reaches its maximum at around 100 days, at which point we cannot expect much more productivity. By then, parties likely know all there is to know about the other parties. We also demonstrate that this relationship holds given a number of important conditions.

Our results have important implications for the understanding and reporting of government negotiations. True, extended negotiations between parties forming coalition cabinets may come with some temporary uncertainty for financial markets. That said, cabinets that have undergone such lengthy bargaining processes may in fact be more productive in terms of making reforms during their time in office. In sum, cabinet negotiations pave the way for more efficient cooperation between the governing parties.