A UK-EU free trade agreement can attenuate the sovereignty debate that spawned Brexit, writes Andrew Glencross. But Brexit will replace an institutionally robust relationship with one that is far more sensitive to public opinion and political partisanship

After a difficult year of UK-EU negotiations, recent media reports suggest there might be light at the end of the Brexit tunnel. This news comes on the back of the departure of Dominic Cummings – the eminence grise behind the 2016 Vote Leave campaign – as Boris Johnson’s top advisor.

The timing could be purely coincidental, but the glimmer of a breakthrough means now is the moment to consider whether a UK-EU free trade deal will be able to stand the test of time. If reports of a negotiating breakthrough prove misplaced, it is equally important to ask whether a ‘no deal’ outcome on 1 January 2021 is a sustainable endpoint for UK-EU relations.

The sustainability of post-Brexit UK-EU relations has received relatively little attention given the preoccupation with following the twists and turns of the negotiations conducted by Michel Barnier (EU) and David Frost (UK). What we know for sure at this point is that the UK wants a less institutionalised relationship, i.e. fewer binding commitments, with the EU.

The UK government’s own economic modelling shows that the weaker the ties with the EU’s single market, the greater the economic cost

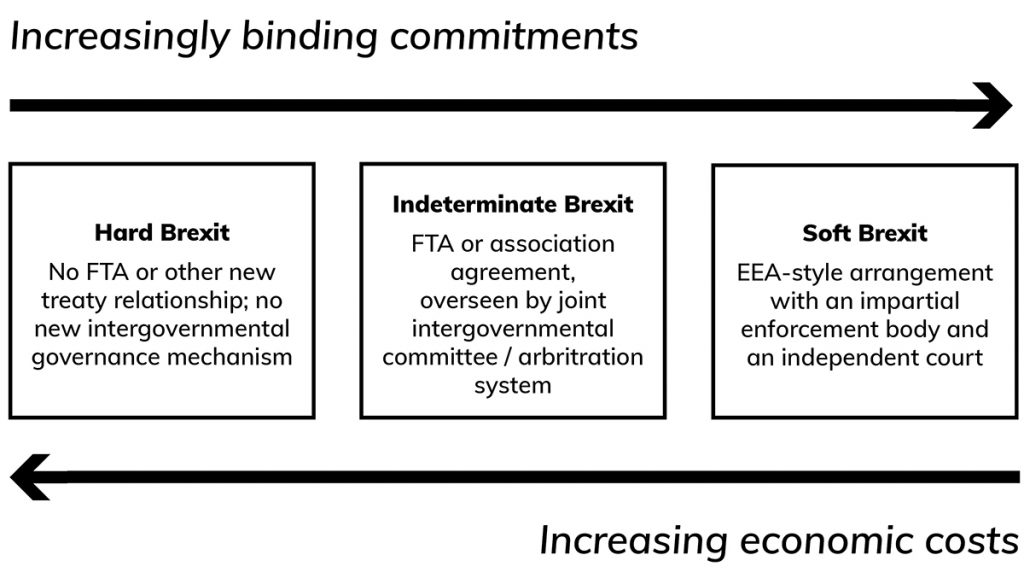

The UK government’s own economic modelling shows that the weaker the ties with the EU’s single market, the greater the economic cost. This leaves a spectrum of options involving a greater or lesser impact on UK GDP, with a free trade agreement (FTA) sitting in-between both extremes, as captured in the figure below.

The soft Brexit option was killed off long ago, although which British politician is ultimately responsible for the decision to forego an EEA-style (European Economic Area) arrangement like that of Norway remains a subject of debate.

The fact is that the EEA, which has an independent watchdog authority and court, is underpinned by the legitimacy of the EU legal-political order. By contrast, Brexit was a decision motivated by the desire to have a looser relationship so that the UK state would no longer be constrained by institutions beyond its control. That is why leading scholars of EU differentiation – the principle of selective participation in integration to respect national sovereignty – conceptualise Brexit as a novel process of managing disintegration.

The process of managing UK disintegration from the EU will not end just because there is an FTA. This is because a UK-EU FTA, as Michel Barnier likes to point out, is a future-oriented document designed to be grounded in common policy goals such as protecting the environment or fighting climate change. To make sense of the dilemma of managing disintegration, as I argue in a recent paper, it is helpful to draw on insights from comparative federalism.

Particularly useful is Daniel Kelemen’s work that looks at the balance of centrifugal and centripetal forces between national capitals and Brussels. Kelemen pinpoints the way political institutions, courts, political partisanship, and public opinion all play a key role in making the EU endure.

For example, member states can defend their interests in the European Council, while the Court of Justice ensures a standard interpretation of EU law across every member state. Institutional and judicial safeguards are less pertinent for the UK after Brexit, but the way partisanship and public opinion might operate in the context of a deal or no-deal scenario helps make sense of the dynamics of future UK-EU relations.

The big advantage of a UK-EU FTA is that it can attenuate the sovereignty debate that spawned the demand for disintegration in the first place. Negotiating such a deal triangulates UK voters’ majority preference for a new trade treaty while respecting UK voters’ antipathy towards free movement, as shown by Sofia Vasilopoulou and her co-authors.

Another advantage of this arrangement is that a trade deal with the EU covering agriculture would largely end the debate over whether to adopt US regulatory standards. Hence an FTA limits the incentive British politicians have to politicise sovereignty concerns in the UK-EU relationship.

a hard, no-deal Brexit creates space for continuing political contestation precisely because of the need to justify this more economically costly outcome

By contrast, a hard, no-deal Brexit creates space for continuing political contestation precisely because of the need to justify this more economically costly outcome. The politics of differentiation would rumble on as the UK seeks to reconfigure its global trade posture to compensate for the absence of a EU trade deal.

Opposition parties, in this context, would presumably support an EU FTA as a way to avoid unwanted regulatory alignment with the US. We saw a glimpse of this strategy during the 2019 general election, when the Labour Party attacked the idea of a US trade deal negotiated by Boris Johnson.

The partisan and socio-cultural safeguards for an FTA are as good as it gets post-Brexit compared with the other scenarios. Yet that certainly does not mean it will be plain sailing ever after.

Managing disintegration via an FTA is a tall order in a context where the UK’s ability to influence EU decisions regarding single market rules is extremely limited. If UK-EU differences cannot be solved by arbitration, the EU as the bigger economy has a far greater ability to impose costs on the UK via countermeasures and absorb costs of any UK trade retaliation. The case study of this asymmetric power is what happened after Swiss voters tried to restrict EU migration.

If UK-EU differences cannot be solved by arbitration, the EU as the bigger economy has a far greater ability to impose costs on the UK

Thus a UK-EU FTA will work best if the UK moderates its future demands for diverging from EU norms. Judged by past performance, this will not be easy.

As an EU member state, the UK had very strong institutional and judicial safeguards for its national interests. But this arrangement did not prove sufficient to counterbalance a party system that kept asking for exceptions and stoking public resentment of EU obligations.

Ultimately, even if there is a UK-EU FTA, the UK will have replaced an institutionally and judicially robust relationship with a far weaker one more sensitive to public opinion and political partisanship.